Thiruvannaamalai to Yercaud, 155km, though it ended up a lot more

I come from a place with no highlands. No real ones, anyway — the highest point, Bukit Timah Hill, is a mere 163 metres. Enough for families and joggers to work up a sweat on Saturday mornings; not quite enough to keep going. You run, you jog, you break up a tiny bit of sweat — then it's time to "descend" for breakfast at the nearby hawker centre.

Not so in India. Home, after all, to the Indian Himalayas. My first time in India was magical, and one I will never forget. As a naive amateur traveller at the time I had mistakenly assumed all mountains were the same. I had only experienced winter, once, in Mount Sorak in South Korea. I remembered four degrees Celsius was quite doable, even without too many winter clothes. I packed just as light, then, for the Indian Himalayas. On reaching Darjeeling I realized what a mistake that had been. This time, I was no newbie: I had been to India about fifteen times since, and knew a thing or two about its disparate climates. I also knew a little bit about its hill stations, and its rickshaws. Something in my body — common sense? — also told me it might be a bad idea to climb a hill station in an autorickshaw.

One of the things that people who know me are likely to say is that I like to do the very things that I'm told would never work.

Like driving an autorickshaw up a hill. Remind me to never do that again.

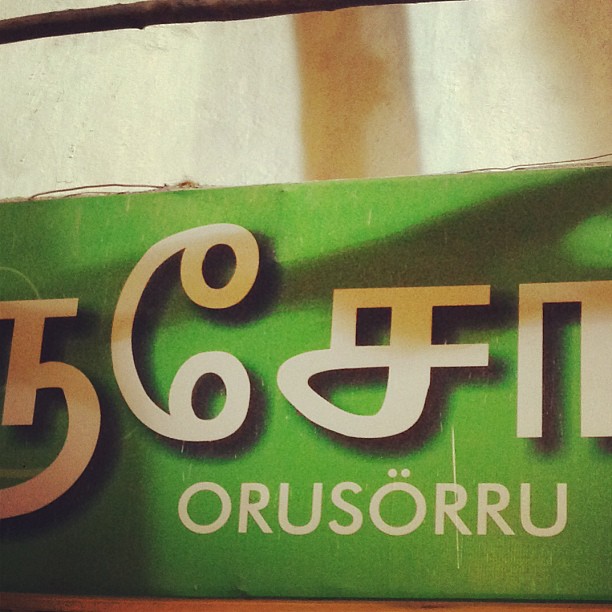

The last we ever saw of our route book.

The real story began the moment we left Thiruvannaamalai. The breakfast briefing made it seem easy enough. Take off at 8am, get lunch somewhere on the way, meet in Harur to make sure everyone was on time, meet again somewhere near Pappireddipatti so we could time our ascent uphill together.

Andrew and I were to get horribly, horribly lost, that day. For the first — and only — time.

Karthik left us that morning in Thiruvannaamalai for Chennai. Having just obtained his PhD days prior to the race, he was slated to move to Brussels soon after. Due to some bureaucratic screw-up, he had to bus it back to the capital for a medical appointment for his Belgian work visa, then head back to meet us in Yercaud that night. Not having a Tamil-speaker onboard was doable, but my team had gotten used to the idea that we could muck around after flag-off, have breakfast, hang out with locals, see a few sights, then start moving.

Flag-off at Thiruvannaamalai was as uneventful as it could be — I could not wait to get out of there. Karthik bid us farewell even before we woke up. When Andrew and I got to base we were pretty sleepy, still, having spent the previous night sleeping on terrible beds (and I on the floor). When the horn sounded and all the teams started for Yercaud, we headed to the nearest coffee shop to eat a quick breakfast (muruku and some other snacks) and to take swigs of coffee before we started properly. It must have been 8am, usually an ungodly hour for me, but the faithful were already awake.

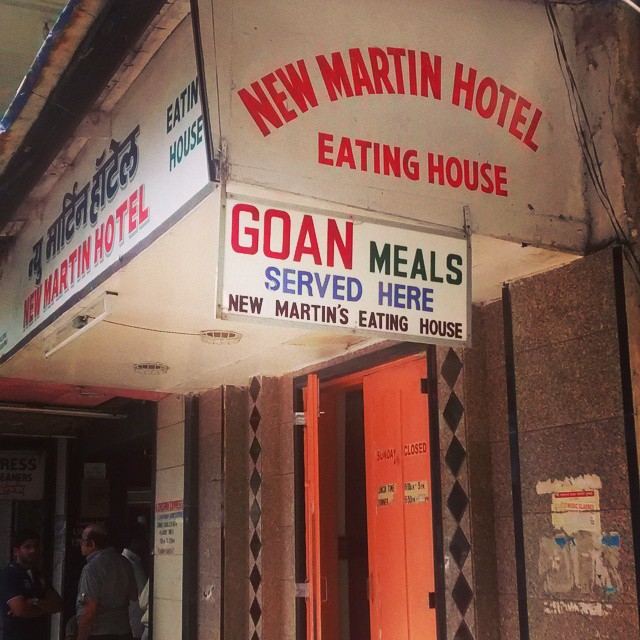

Hungry, we had kothu parotta in Kambainallur.

At the coffee shop near a temple on Chengam Road, we looked quizzically at the legions of old, white people in "spiritual clothes". I looked even more quizzically at the firingi prices we were obviously paying here for muruku and kaapi. We read the newspapers, chatted a little, then with some reluctance got back into our rickshaw to begin the drive. Still no clue what we were in for. You know how some mornings when you wake up you drag your feet and don't want to go to work?

That morning I woke up and dragged my feet and didn't want to drive my auto. Off we went anyway. My job, since I was no good with driving these things, was to sit in the backseat and navigate. My tools? Google Maps on my iPhone. Google Maps in this part of the rural world was fine — if by fine you mean, places, villages, towns and cities actually show up, in English. The directions they came with were impossible. Being from the big city, you understand: if Google Maps screws up, it is the end of the world as you know it.

So we followed these maps on my phone, and the navigational directions they gave us. Except that we got hopelessly lost in the end. We kept going anyway, and the people we'd stopped for directions were no help. "Which way to Harur?" This way, that way, you go straight there and then you turn left… India is a pretty bad place to get lost in. Everyone wants to help, and does; except when you're lost, all that help is really no help at all. At a petrol station we got the usual "OMG, foreigners! Driving a rickshaw!" curiosity. And still no worthwhile directions. We kept driving, driving, following one lead after another.

We passed lots of farmland, and lots of construction. We drove over bumps, we drove on very awful roads. We found ourselves in a village where I got out, and gesticulated wildly. Yercaud! Yercaud! Which way? (Making a note to myself that I should have paid attention to what little Tamil was spoken around me, growing up.) "There!" — followed by the Indian octopus. The one where at least eight arms point in eight separate directions. If you're a newbie you end up following directions given by the person who made his case most forcefully and most convincingly. If you've been around these parts, it's that guy you learn to ignore. We kept driving, in some direction.

With another happy passenger. Fare: zero rupees.

More farmland, more cows, more farmers and more awful roads. The lead we had followed previously now led to what seemed to be a dead end. I jumped out of the rickshaw and gesticulated wildly. Is Yercaud back there — pointing at the direction in which we came from, so at the least we could find out if we were going in the wrong direction — or that way? Nope, all the answers came fast and furiously. It's the other way, just keep going.

I was driving on one of the smaller highways, emboldened by how easy it was becoming, when the highway suddenly led into a town, and the town led to lots of people. Remember, I don't really know how to do this — I'm just not good with manual gears, not yet — so I suddenly felt I could not control the rickshaw, and it was cruising along at a speed that was much too fast even for an small town. Andrew, who was chilling out in the backseat, was starting to realize this too.

I kept going anyway, freaking out and yelling "ANDREW I NEED YOUR HELP!" but by the time he scrambled and leaned over to take control of the gears, the rickshaw had already hit a motorbike. There was an old man on it. He fell. I felt like everything that could have gone wrong already had — and yet here we are, about to be in the middle of a large mob with possibly no way of getting out of it.

True to my projections, a large mob had formed around us and the old man. But they were not yelling, nor were they demanding anything. They gathered in large numbers but then some of them helped him up from the ground, another group picked up his motorbike and brushed off the dust, and others yet just stared at us. "It's okay, just go," the mob was saying. But I knocked over someone's bike and it's possibly not working now! "No, he's fine, you should get on your way." I tried to give the old man some money to fix his bike. He shyly refused, acknowledging the power of the mob around him. They were so nice to us, almost to the point of assuming that we must have been so unlucky to have had a tiny accident here in their town, even though it was my fault, that I felt embarrassed instantly. Knowing I could not out-talk the mob, not in a language I didn't speak, and not wanting to embarrass the old man either by insisting openly that he take my money for his bike, I made it seem like we agreed, gathered our stuff, and got back into the rickshaw. But not without shaking the hands of the man whose bike I had knocked over (even if it was gently so), and pressing a small wad of cash into his hands. We took off then, and kept going.

Then the phone rang. It was Aravind, wanting to know where we were — everyone had already assembled somewhere for lunch — so where the hell were we? Ask someone, he said. With no Tamil between Andrew and I, and sign language not cutting it for when actual explicit directions are required, I passed the phone to someone who spoke in Tamil to him.

When I got the phone back, Aravind calmly told us we were at least two hundred clicks in the opposite direction. Please drive back towards Harur ASAP. Still the villagers pored through our route book, and were unanimously convinced we just had to keep going, there would be a turn, go up that hill, and then it'd be Yercaud. I could see it, and I wanted that hill to be Yercaud, quite desperately. But of course it wasn't.

So we doubled back and drove off in the other direction.

One hour. Still no sign of Harur. We were, instead, in Kambainallur. This being a good-sized village, and by this I mean there was actually a place we could stop and eat a proper meal in, we parked outside a little hut where I saw something I recognized. An iron griddle. With food on it. Food being kothu parotta, one of my favourite childhood foods. This far out from home, and from the places I knew in India, having something close to home like kothu parotta was a wonderful feeling. It reminded me of all those nights I walked from my university hostel in Singapore to Little India to eat parotta, chopped up, with egg and chicken. I decided I would have the same thing right here in Kambainallur just so that I could feel we might somehow find our way to Yercuad later.

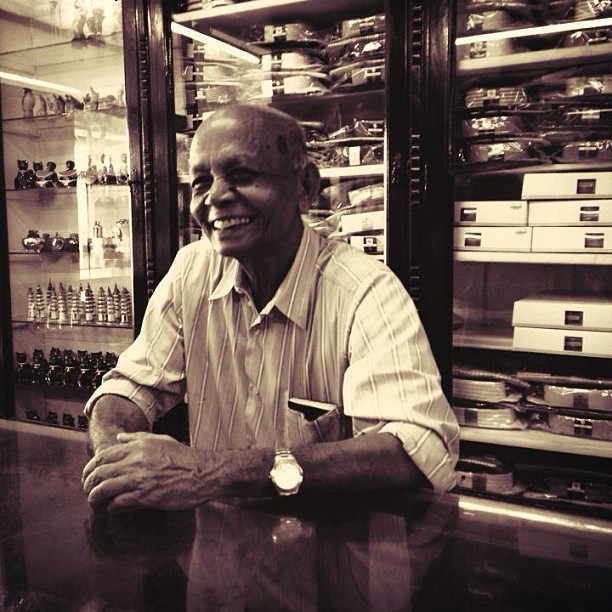

The people at the restaurant were bemused, to say the least. When I think of rural Tamil Nadu now, I will forever remember it for the sweltering, still heat beating down on our backs. No wind, no breeze — just the slow oscillations of a very old, very dirty ceiling fan. Tic. Tic. For half an hour we ate our tasty kothu parotta in the hut, and entertained the people of Kambainallur who were coming into see what we were up to. Yes, we are driving this thing…

I'm often asked, wasn't it dangerous? Dangerous, to the extent of possibly damaging life and limb on the road, yes — theft and other crime, not so. We usually parked our auto somewhere in sight. By the time we were here in Kambainallur we had gotten so comfortable in this part of Tamil Nadu we even experimented with leaving our bags of expensive camera equipment in the rickshaw, although well-disguised. Every single time we — as foreigners in this part of town — were treated with far more curiosity and amusement than anything we owned (which probably didn't look like very much, considering how we were dressed).

We clambered back into our rickshaw with a small post-lunch stupor, armed with cold Pepsi and Thums Up, and took off somewhere into the distance. This time we had a small feeling we might be on the right track. We kept driving, and noticed people were trying to flag us down. This time we were in the small country roads that cut through the villages, not on the state or national highways, and not on the larger arterial roads between the towns either. There did not seem to be any public transportation — nor any other autorickshaws — around for miles. We decided since we had just had a small spot of good luck (with the tasty lunch and finally figuring out which way to go), we would pass on the karma. We began picking up passengers.

All of them were going a short distance, usually to the next village, so each ride lasted an average of 10 minutes.

With our music thumping in our rickshaw, food in our bellies and cold drinks in our hands, Andrew and I started feeling rather invincible. We stopped for every single passenger who flagged us down. Each time, happiness as we drew to a halt, then confusion, horror, as they looked into the vehicle and found us looking like that. They all climbed in in spite of the incongruity. Not knowing how to speak with them we simply drove on straight, and they told us when to stop.

Lady we gave a ride to in Kambainallur.

First, an old lady near Kambainallur who wanted to go to her sister's house. She climbed into the backseat with me, her orange sari so long it flapped into my lap. She was mostly silent, being rather shy as some rural old ladies can be, only using her hands to direct how we should go to her destination.

After a few minutes, her curiosity got the better of her and she asked, in Tamil (which I understood a very limited amount of), "Where are you going?"

"Yercaud."

"By rickshaw?"

"Yes. From Chennai."

"Why didn't you take a train? It's so much faster."

With that, she pointed to the village she wanted to alight at, and ran off into her sister's house. I often imagine what she might have said to them. "I came here to your house in an autorickshaw, driven by an American and a Singaporean, and they were dressed like rickshaw wallahs." I often imagine that might have been the rural equivalent of saying you just saw a spaceship.

We kept going. We picked up at least four people, each of whom was just as incredulous as the last. One man had huge gunny sacks of spices with him, and he too sat in the back seat with me. Each started out shy, embarrassed, but burning with curiosity — each ended up wondering why we were doing this. At that point I was starting to wonder myself.

One happy passenger after another, we were finally well and truly on our way. Harur was in sight. Our team phone was low on battery, so we had no communications from the Mothership (the convoy) since the last time we spoke. We found that M., who was responsible for making sure all teams got rescued if anything went wrong, had been waiting in Harur for us for hours. His pickup truck was recognizable from afar, so we drove up to him. It was 4pm. All the teams started making their way up to Yercaud about 3 hours earlier. "So you better start now before it gets dark."

At Harur I don't think either of us had any idea we were only halfway there. It seemed such a tremendous accomplishment to have made it thus far. I started to feel relieved, like we could take things easy from here. We even celebrated with a 20 minute fresh fruit juice break. But we were to face a truly uphill battle.

We left Harur and made for Yercaud. We were so hot and dazed and frustrated by this point that even the relatively straight road towards Pappireddipatti, from which we would begin our ascent, was difficult to find. M. drove his pickup truck alongside, doing the convoy equivalent of kicking our asses, and we were finally in Yercaud!

Not so.

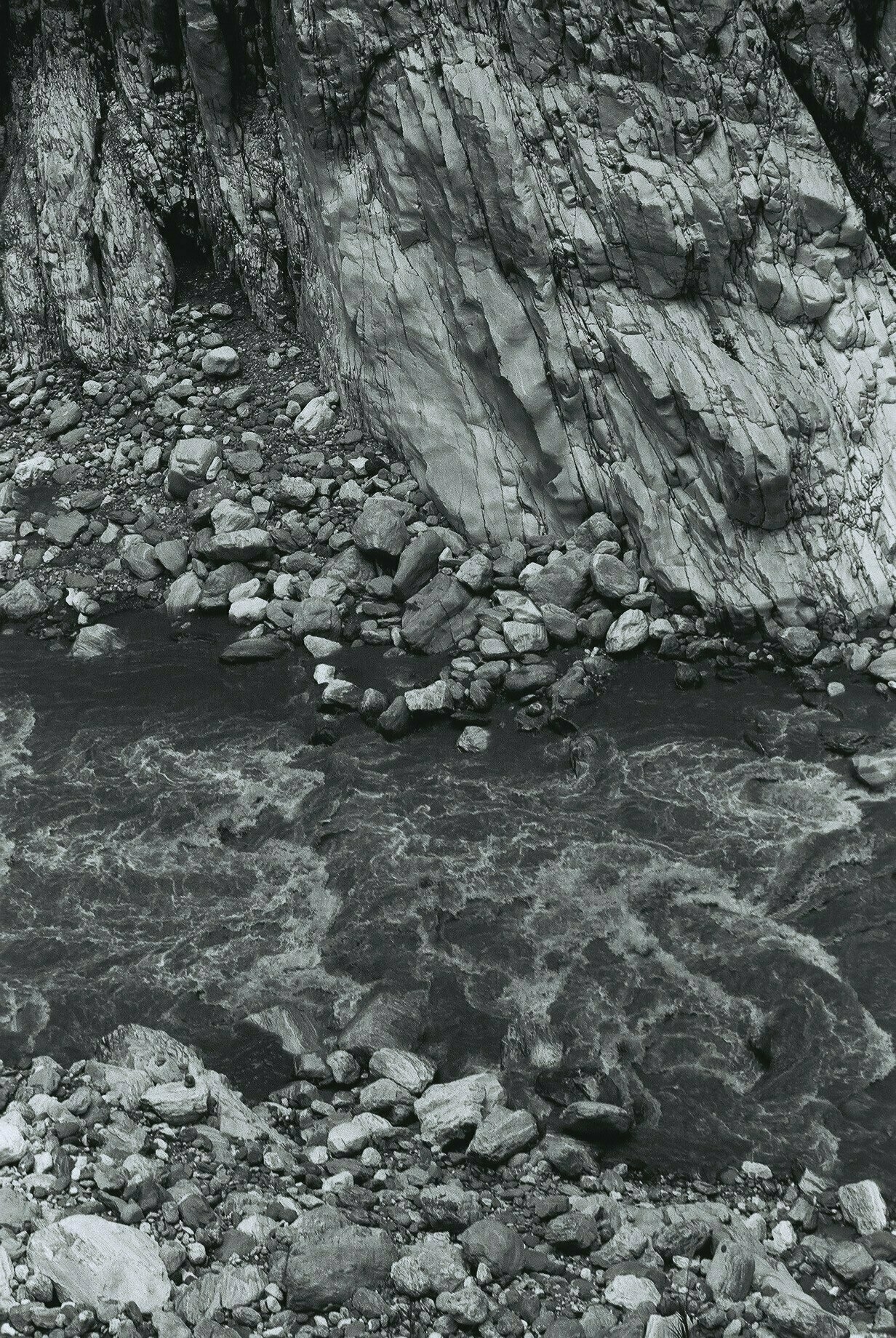

After 45 minutes up the hilly roads into Yercaud, a gear and brake problem we had been ignoring for the last four hours began to act up. The rumbling sound from the rickshaw was growing so much louder we had to pull over on the side of the hill. M. was not far behind, so we got him to take a look. Yet another 45 minutes spent not-moving, even though M. had really talented mechanics working with him, the sun began to fade. I have been to many places in the world and I'm supposed to be used to this — but it takes a huge effort for me to remember that when the sun sets, sometimes what follows is total darkness. And so it was. "Turn on the front lamps," I said to Andrew. "But… they are already on." They were just feeble, and really quite pointless. We could not see a single thing. M.'s team sped off and we soon lost them, driving in the dark ourselves. Our feeble lights did as much as to allow us to see when something was immediately in our faces, but not much else.

We were heading to the base hotel, but there was still a substantial climb to make. We were probably driving in the dark for about an hour before we finally saw a sign that said "Glenrock Estate" — our base camp for the next two days. Despite following the signs, and the instructions we received earlier, we could not find it. We would go straight, make a left bend, and then be in complete darkness again with no signs of a hotel anywhere near us. We kept going in what must have been circles in the dark. When we finally saw a bunch of lights, we knew it was not the hotel but the small village of Kakampatti. We pulled over for me to get some directions.

I ran into a store with a telephone, and dialled hopelessly for our friends. No luck — nobody had any cellular reception at the hotel. I asked a few villagers where Glenrock Estates was, and they said it was just ten minutes away, just up the slope we just came down from, where it was so dark we could not see the sign that said "turn right", so we missed that completely. When I got back to the rickshaw and to Andrew, he was on the ground peeking into the underside of our rickshaw. Disaster, yet again.

A bolt had fallen off the rickshaw some time in the last ten minutes. It could not start without this bolt — there was a risk the rickshaw would simply fall apart, if we did. But it couldn't even move at all. At this point I was beyond wanting to cry. Somehow I had some blind faith in how India always comes together for me.

A villager got on his motorcycle, and said he was going to buy the part for us from the garage 15 minutes away. When he returned, we found he bought the wrong bolt, and before we could even thank him for his help he got back on his motorcycle with someone who knew more about mechanics than he did, and they both went back to buy the proper part.

I sat on the ledge, wanting to help but really not being able to, just tired beyond belief. It's the sort of feeling when you are not sure when the work day will end — except in this case you don't know when the day will end, or whether you will get to where you need to be. I was fully prepared to spend the night in the village.

Suddenly, loud roars came riding down the hill towards us, and two men on quad-bikes came towards us.

"You must be Adrianna and Andrew."

I thought they must have been angels.

"We're the Bosen family, from Glenrock Estates. One of the village kids ran up here to tell us, quite breathlessly, that there were two foreigners whose rickshaw had broken down in their village. Since you were the only people not here yet, we assumed it must be you."

The beauty of my mother India is in how in spite of the chaos, things come through. If you don't panic, if you don't worry too much, if you don't allow yourself to be swept away by how different, and how insane, India seems to you, she will be good to you. Our rickshaw stayed in Kakampatti that night, but we didn't have to — we got into the quad-bikes with the Bosens, and they brought us uphill to their comfortable coffee plantation estate where we joined the teams around the bonfire, with Kingfisher and coffee magically appearing each time we wanted some.

Coffee. Beer. Food. A comfortable bed, even though it was one I shared with 20 other beds in a dorm, I was happy we made it. Now that the worst was out of the way on the second day of the race, surely there could be no worse moments hereafter?

The villagers of Kakampatti fixed our rickshaw for us, and even drove it to the hotel when they were done.

Yercaud may not be in the Himalayas, or any other majestic mountain ranges, but as a compact and quaint hill station in the Shevaroy Hills it was all I needed it to be, right there and then.

Aside: Visit the Bosens at their lovely Glenrock Estates in Yercaud! Great coffee and quaint place to stay.