Posts tagged "wobe"

← All tags

April 5, 2018

It’s been a while since I’ve written about work. Even longer since I’ve gotten on a bicycle.

In so many ways, running a startup is like a race. Some people like to do sprints. Some people like lycra.

More and more, I find myself preferring endurance sports and comfortable clothing — perhaps because that’s the closest sporting analogy I can find for the kind of work that I do.

In 2014, I moved to Indonesia to work on ‘financial inclusion for women’.

In 2015, I completed the ideabox accelerator, worked with no salary for a year and a bit, and worked on finding product / market fit.

In 2016, I finally raised my first tranche of funding. At that time, ‘Indonesia’ / ‘emerging markets’ and ‘social impact’ were three things that didn’t go together.

In 2017, I lost both of my cofounders for personal reasons, and struggled to not burn out myself. I did not succeed.

In 2018, I am still going at it. Wobe is growing everyday. We have great investors. I am supported by a team of hardworking people who are not only great at what they do, but they also believe that we can use tech to bring financial inclusion to emerging markets.

Grit and resilience don’t come naturally to me. I understand them as concepts and I live, to the fullest extent that is possible, with as much as I can muster. I’m also painfully autistic; I simply don’t see risk. Risk is not a discrete concept, nor is it something I can grasp. Therefore, it does not exist.

Early stage startups are hard.

You risk: running out of money, running out of steam, running out of time, running out of energy. Everything needs to be in perfect alignment and timing. You have to fashion a product and a company into existence, and do both really well, in a remarkably short period of time.

All of your flaws are amplified.

Everything needed to be done — yesterday.

Everything is broken. Everything is great.

Like so many startup folks, I decided to work it off. Triathlons are especially popular with us. I suppose if you do what we do for work, weekend competitions that are physically and mentally demanding are just yet another challenge. Another hill to climb. Another bendy road. Another slope to descend.

I did a bit of that, and I’m pretty good at it. But I realised my taste in sports is the same as my taste for business. I need gravel and mud. I need to fly face first into wet muddy terrain. I need to find a hill I’ve never climbed, with the equipment I have, and just pedal furiously.

I feel like I do that everyday at work, and everyday at play.

I’m at home in places where conditions are rough.

I like unpaved roads.

Maybe that’s why I’ve chosen to build a business in a space I care very much about (increasing access to financial services for the unbanked), in a country I love with all of the opportunities and challenges (Indonesia).

The road ahead is bumpy, wet and rocky. That’s when I know it’s time to hit the gravel.

Thank you, friends, family, investors, Wobe team members and our customers, for coming along on this ride. You push me to do better, be better, learn everyday, and do my best. Burn out is not fun. You lose so much time and focus. Growing is so much more fun! I want to share more stories from the trenches, growth, warts and all.

Invalid DateTime

When you work at Wobe, you’re bound to have conversations like these at some point:

“Can you check on this transaction for me in dumplings?”

“Let’s make some changes to kaya.”

“This PR removes the confirmation code from diplomatico request”

This is a feature, not a bug.

We’re a company founded by foodies, but our engineering team is the foodiest of all.

Deep within our repos you can find things like:

Coconut makes the world, and our infra, go round.

Coconut makes the world, and our infra, go round. Dark, golden and distilled beauty. Just like our microservices.

Dark, golden and distilled beauty. Just like our microservices.

Since we’re a multi-cultural team, with 2 engineers from Venezuela, we were also happy to christen one of our most important packages after Venezuela’s most famous product, Diplomatico.

One of our internal web apps we call, lovingly, Dumplings. That’s because all of us love dumplings of all kinds. Chinese dumplings, momos, gyozas, manti, mantou, har gow, ravioli, tortellini, xiao long bao, samosa, wantons. If you don’t love dumplings, you can’t work for us. (JK!!)

As our infrastructure and services expand, we’re going to need many more food and drink names for them.

We crowdsourced some ideas within the team:

- sushi

- rendang

- cokelat

- pempek palembang

- siomay

- jeruk panas

- gulai kambing

- dendeng balado

- martabak manis

- dosa (the South Indian breakfast, I like this especially also because it means ‘sin’ in Indonesian, which it is.. with all the ghee)

- cumi

- negroni

- ramos gin fizz

- arepa

- pav

My personal vote, however, would go to Ramos gin fizz. With just a few simple ingredients, vigorous shaking either renders a masterpiece — or a flop. Like bad code, and bad engineering practices, a bad Ramos gin fizz doesn’t even resemble the real thing.

Invalid DateTime

As the cofounder and CEO of a tech startup working to improve financial inclusion in one of the world’s largest countries that is also one of the largest cash economies, I have amassed a wealth of odd knowledge on how cash works. How it works, specifically, at the intersection of people and connectivity. It always excites me so that there is a world of difference in how different places have different assumptions about payments.

My first world assumptions already went out of the window when I spent a year in Myanmar before SIM cards went down in price from $2000 to $1. There, bags of cash were king. Bags of cash under a desk, even better.

Here in Indonesia, we faced the same challenges as most other companies: how do we accept payment from the average person? For our customers to start selling pulsa (airtime), internet packages and other products with Wobe app, we need them to first pay us for their prepaid account. (Here, you can also buy a cigarette by the stick when you want to smoke it, instead of buying an entire pack. The same is true of phones.)

Happily, this is why we do what we do. Before you can improve on something, you first need to know it well.

Not reinventing the wheel

It helps to examine the prevalent norm.

In Indonesia, you commonly see what can be described as “hacks for the cash economy”. These are necessary ‘hacks’ through a set of circumstances entirely unique to Indonesia; with more than 17 000 islands and a sparse population outside of Java, cash is still king here, and will remain so for the foreseeable future. Distribution and reach (of ATMs, banks, etc) is only one part of it.

Other than cash-on-delivery, it is quite common to pay for things online in any of the following ways:

- Asking a friend with a bank account to transfer the payment for you

- Standing in line at a bank, where you do not have an account, to make a manual transfer

- Going to a convenience store to tell them you want to pay for say, a flight ticket; waiting 40 min for their payment system to boot up, then finally making a cash payment

As you can see, large companies have armies of people just staring at internet banking screens to verify each and other transaction in real time.

What has emerged as the de facto way of taking manual cash payments is so unique and elegant, and so characteristically Indonesian: randomized unique codes that almost function as convenience fees, cheaper than credit or debit card percentages.

In many ways, Tokopedia has been at the forefront of Indonesian ecommerce. As one of the pioneers of the 3 digit unique code method, we were impressed at how simple yet effective it was — for both the consumer and the company.

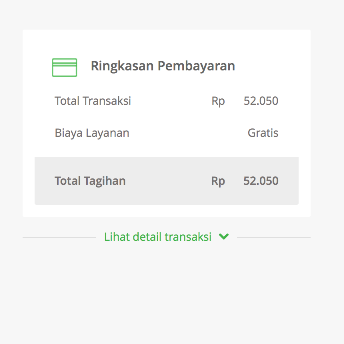

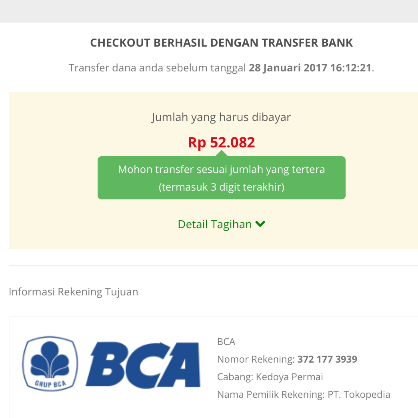

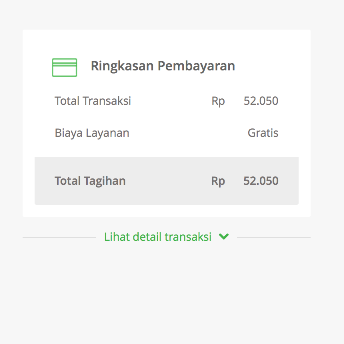

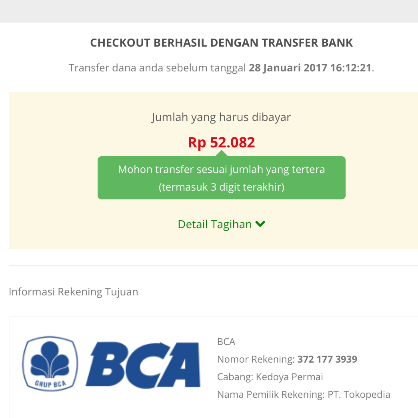

Assuming I want to buy a USB-powered electric fan, or kipas, which costs IDR 52 050 (USD 3.91).

If I were to select the cash / manual bank transfer method, I would see this screen:

My total, with the unique code (+032) added to the final bill.

My total, with the unique code (+032) added to the final bill.

All Tokopedia would have to do would be to verify that they had indeed received a transfer of IDR 52 082 on that day.

It would not matter from whom, the payment came from, or whether it was successful or pending (manual payments can be seen as pending after a certain time in the afternoon, depending on the bank and only available the next business day—which makes Fridays and weekends particularly difficult). The existence of that exact amount would suffice.

How that inspired us

It would be easy to wish that every market was exactly the same as where you are familiar: but that mentality would not take you far. Anywhere, but specifically in Indonesia.

As a company that has betted its entire future on the 4th most populous country, it has always been in our DNA to operate within the frame of what works here, and to never once claim to know it better.

We believe that the future will be a mix of unique ‘hacks’ like these, along with a substantial push towards the digitization of payments (more on that in a bit).

I’m proud to announce that the next feature we will have in the Wobe app, will be our very own version of the randomized unique code. We are currently testing it but it appears to be a huge improvement to our top-up mechanism. All of our product and business decisions are driven by the simple question: how does this improve the lives of the people we claim to work for? In this case, we will be able to easily take payments from individuals who may live as far as one to five hours away from a bank, an ATM or a convenience store.

What is the way forward?

How does one reconcile the two Indonesias, then: with one foot so violently in the future, with its obsessive love of mobile phones and social networks, and the other so virulently enamoured by the ease of cash?

Short of pushing the country towards bank accounts and debit and credit cards, what looks likely is this: there will be a peaceful coexistence of cash and digital payments. In some ways, Indonesia will lead the way in Next Billion tech, ecommerce and payments. If India’s PayTM and China’s Alipay are any indicators of how a hinterland with a large population and a unique set of infrastructural and geographical challenges are anything to go by, I believe that in 3 years Indonesia will find its own beat. Which is why we do what we do at Wobe: we believe that if we build a product that helps the average person participate in the digital economy, we will be able to find innovative ways to make a difference.

What we do best is to empower women to be the missing link between their communities and the world of online opportunity. Be it in small features, like randomized topups, or in the big ones—like creating financial independence sessions for the women we work with—we are driven by our mission to do well and to do good.

Perhaps one day there will be a new school of thought on product design and enterprise: how to create and design with empathy, as if our lives depended on it.

Our next build will feature the randomized topup feature.

Invalid DateTime

How to create products for emerging markets

Nearly everyone wants to cash in on emerging markets. Facebook wants to fly drones to deliver internet connectivity over rural areas. They may or may not collide, in scale, ambition and delivery, with Google’s balloons (link). Whoever you are, emerging markets are hard.

Every time you see a Singaporean or Malaysian startup raising a fund, you see them want to expand to Indonesia, like it was a mere thought_._ How do you make apps, websites or any kind of media for a market so different from anywhere else in the world?

In our case, coming to Indonesia to create a product aimed at the last mile in a country of 17, 508 islands has been some of the most challenging work we have ever done.

As a cofounder and first product owner, here is what we did.

- Listen. It is not possible to parachute into a place so fundamentally different, so unique, with a suitcase full of tips and tricks that have worked elsewhere. We listened extensively. Who you listen to can be just as important as how you listen. We went right to the source: we literally had listening parties where our target customers, who are Indonesian housewives and students, had fried food and sweetened tea with us as we studiously thought about how our product could work for them. Before writing a single line of code.

- Iterate. Anyone who has put an app or a website together knows that constant iteration, improvement, is key. From our paper prototypes to our app version 3.7.5, our iterations have come a long way. There comes a point where iteration has to be backed up by metrics, though when you are just starting out, flexibility and rapid adaptability is more important.

- Speak their language. Literally and figuratively. We found, for example, that in some locations it is not wise to send out young men into conservative neighbourhoods. From the early days of visiting homes and communities as a merry band of random people with clip boards (and fried bananas), we now have community leaders who are respected and respectful. It is sometimes still funny to trot out my Singaporeanized Indonesian as a joke, but when work has to be done we always get so much more accomplished by reducing cultural, linguistic and other kinds of friction.

- Consider all assumptions. Thinking on the intersection of product and business is hard enough. Thinking about it without assumptions can be very difficult. Somehow, it seems even harder for some to do this without being condescending. If your starting point in building a product is, “Indonesians like X”, you are on the wrong track.

- Conduct ethnographic research. This may be extreme, but I consider it very important to live in the same environment as the people who are likely to use Wobe. Paying for my (prepaid) electricity just like everyone else in my kos-kosan, standing in line to pay for my online purchases including air tickets with cash, all of those things were essential for our product. Very soon we will be able to pay for all that with Wobe. Extreme ethnographic research helped us begin our journey from idea to product, from the same starting point as our customers: in cash, in line, in wait.

- Consider your stack and architecture. Where we are it is still PHP-land. Services are massive, not micro. Hosting is local, rarely in the cloud. Bandwidth can be narrow and coverage can be spotty. We knew we had to avoid building a traditionally synchronous app to have any chance of Wobe working well outside of the cities. More than ideology, our micro-services architecture is supplemented by the concurrency of Go, the ease of native mobile development with React Native, and a team-wide obsession with improving performance and cost savings for our customers (every byte counts..).

There was scarce literature for us when we started out on this journey, so we hope in the months to come we can share what worked for us. If you’ve built something for an emerging market, what worked for you!

Invalid DateTime

Wobe’s founder on the basics for technical success

“Jakarta Panorama” by Gunawan Kartapranata [CC BY-SA 3.0]

“Jakarta Panorama” by Gunawan Kartapranata [CC BY-SA 3.0]

If you’re a founder too, technical or not, you’ll know all about the struggle.

The struggle: late nights, being poor, having everything go well and then not, the very same minute.

For me as a non-technical founder, and I’m sure for many others, the struggle is also: how do you build things? and other assorted questions.

If you build it, will they come? (Customers)

How will you build it? (Teams, product, culture)

What, indeed, do you build?

I’m always perplexed by founders who want to only move fast and break things without knowing themselves what they’re moving or breaking. If you ran a furniture company, had aspirations for it to be the best in the world, wouldn’t you want to at least know how to wield a hammer?

This post documents the who, what, why, how of our year-long journey building technology in the emergi-est of emerging markets: Indonesia.

Wobe works to improve access to payments and utilities at the last mile: our unique application and its surrounding ecosystems of microservices and tools let us offer regular people the opportunity of running their own business. They can sell recharge (of phone airtime, data, electricity, water and other vouchers); their communities benefit from cheaper and more efficient ways of topping up, without having to travel. We work with grassroots organisations to bring about greater benefits for low income women who come into our networks.

Who we build for

More than how you build or what you build, is the question: who do you build. This is tied to the mission of the company, and resonates through the company. It also has to do with what the founding team, not just founders, cares deeply about.

I had the amazing opportunity to spend a year in Myanmar, right about the time it was ‘opening up’.

Despite the $1500 SIM cards and the bureaucracy, Myanmar helped me fall in love not just with a country or a region, but with the idea of very hard problems. How will Southeast Asia go from our cash-only economies to online, digital payments? Will women and minorities be left behind? Wobe seeks to answer these questions through the tech we build, via the business relationships we build, and within our team.

We build for them:

(Above, Wobe growth activities in Sumbawa, eastern Indonesia.)

Nothing is constant in emerging markets, except for how things change all the time.

Our community anchors us:

- Empathise: we carry out internal and external research activity to help us make product and business decisions and know our customers

- Understand: we do not assume everyone has a fast internet connection. We know from our research that our customers are price-sensitive, and cautious about data consumption. For this reason, our product (a) has a tiny footprint (b) performs better than most other apps in lower connectivity

- Prioritise: it would be far simpler to use established payment gateways and accept credit cards in-app. Our customers do not have credit cards. It would not make sense to make product decisions that work for only a small percentage of our total addressable market.

Here’s a sneak peek at some of the building blocks at Wobe:

Building the Team

For every founder, the quality of technical team and your technical decisions has a ripple effect. I can’t emphasise this enough. Even when you’re a one-person team, what you decide on this front will have long-lasting impact.

Your main options, pre-funding, are to either find a technical co-founder (a unicorn; stop searching, but more on this later), outsource, or to do it yourself.

Unless you’ve already built products at great scale, and / or run a team to do that, doing it yourself may not be the best use of your time.

For many, the likely choice will be to outsource. All types of dev shops and individuals will be happy to build you an MVP for anything from US$500 to US$100 000. Your mileage will vary greatly. Whatever decision you make on this, do not establish mediocrity as a standard. The quality of your future incoming team, if there is one, will be pegged to the ones who came before. Nobody wants to work with a Z team. Nobody wants to clean up Z-team level excretion.

Wobe’s technical journey was a long one. In the next few posts, I will be happy to share what that was like, how we built a product with very little money, how we thought about technical hiring, how non-technical founders can improve their technical hiring pipeline.

It has a lot to do with first acknowledging you don’t know all the answers. Even if you are a technical cofounder yourself, you don’t know all the answers. Then assemble the best* people who care deeply about your mission.

Our mission is to build tech that works for the people who need to rely on us. We succeed when they are able to increase their family’s income level by a dollar, or a few hundred, because of what we do.

Given the many questions we’ve had to ask, and impossible mountains we’ve had to scale, I want to set a clear path for us as a company. Wobe will be an open company, right down to our core: our code.

In the coming months, my team and I will share how we write Go, how we hire; how we work cross-culturally from Mexico to India and Indonesia; how open source will be a pillar in our company. What is culture?

Culture is not free beer and beer pong. I doubt that anybody really knows what it is.

Let’s find out here together, shall we?

October 1, 2016

I've started writing articles for Brink, a new media publication by the same people behind the Atlantic. My first piece is on Tech’s Role in Reaching Indonesia’s Rising Middle Class.

April 21, 2016

I'm seated now by the side of an old vending machine in Jakarta airport, with power sockets so dirty and old I had to think twice about plugging my cables in. Yet in all of Terminal 1, one of the oldest airport terminals in a country not known for modern aviation facilities, there was only this one socket free. Confined to my fate of temporarily sharing power with a giant Teh Botol (not Coke!) machine with no seat within range of my Macbook charger, I am, obviously, on the floor yet again.

Sitting on floors: a practice cultivated in many countries across the world. Sometimes involuntary, most of the time because my inner hippie wants me to. The difference between now and then — I am now at the kind of age where you would, if you did not know me, expect some kind of manners from me. Wear proper clothes, wear proper shoes. Sit on proper surfaces. I imagined I would too! That one day, I would finally learn how to be proper. How wrong I was on that, and many other fronts! I am happy to still-sitting-on-dirty-floors. No — I am overjoyed. Overjoyed to be still a chapalang, anyhow and anyhowly chapalang person.

So much has happened since the last real post of any substance here. Mid, early 2014 perhaps. I started a company. It still lives. I have teams, collaborators, all across my different endeavours. The foundation I started in 2012 is still alive, too. I am relieved and grateful for all of the opportunities thrown my way, all of the paths revealed and then some.

Why did I not write? I did not write, because life overwhelmed me and kept me away and sometimes light-headed. I did not write, because I forgot how to. It isn't like riding a bicycle — it's more of riding a unicycle where you know eventually you'll find your balance but only after falling flat on your face anyway, no matter how many times you've ridden one. In my pursuit of achievements, exceptional or otherwise, prizes, awards, Silicon Valley-style work yourself to the bone for some big undefined payoff (emotional or otherwise); I lost myself in the race. I lost myself, too, in the unclear idea of what it meant to be an adult.

An adult, I was told, lived in a proper house with a proper bed with a proper pillow (for all of the neck pains you're bound to have). I have neck pains, indeed, but realise I can do without all of the rest. I haven't sat on dirty airport floors for years. I haven't gone somewhere with nothing in my bag other than the clothes currently on me, in years. I haven't gone somewhere without a plan, without a place to stay, without any idea of what i was going to do. I don't know how else to live, and forcing myself into being the opposite of those things brought me further and further away from who I really was.

Maybe this year, after learning to like myself again, I'll finally get my groove back again. I'm proud to be an anyhowly person. I'm proud to extreme and spontaneous. I will no longer knead the image of who I truly am into the uninspiring ideas of what some people had wanted me to become. I don't want to achieve things for the sake of doing that — I want to learn to be alive, again. Let's see how we go on this journey, I'm excited but also shit-scared about it.

But as I once believed (when I was much younger) — if it doesn't scare me like hell, it probably isn't worth doing.

Invalid DateTime

I do quite a few things. Run a startup. Run two non-profits. Mentor queer kids. Spend a lot of time with my family, partner and our dog. Play video games. Paint the house. Cook for friends. Take my dog on long walks. Even, gasp, sleep!

A lifetime ago on my first entrepreneurial rodeo, I did not know many of the things that I know now.

I know now, that:

- Sleep is the most important, ‘sleep for the weak, no sleep till I’m dead’ is just pointless and unhealthy bravado – because I got so close to the edge

- Health is important. Many of my peers have now had a few attempts at entrepreneurship, and many of us have worked ourselves to the bone and back

- Focus is everything, and time management is better. There’s no value to working insane long hours when you’re not focused. I have better awareness of my attention span and focus patterns now (short bursts, varied, always have to be doing something insanely fun or difficult, preferably both)

- Neglecting friends and family isn’t ideal, they’re worth a lot more than most business. You also get better at navigating friendships vs acquaintances

- Saying no is okay

- Saying yes to things that matter is also

- Getting something done imperfectly is better than waiting for perfection

- Being busy is a state of mind

Some people are perpetually busy. Maybe some people really are genuinely busy. I try to be un-busy, which is not the same as being unproductive. Even if I’m really busy, I want to never say I am. I will always have time to chat with a suicidal friend who calls me at 4am. I will always have time for anyone. I will always have time for my dad, mum, girlfriend, siblings, nieces. I want to always have the head space to be actively learning new things, instead of blocking anything being of a mistakenly diagnosed case of busy.

There’s a difference between being consciously un-busy and being frivolous. I suspect I might have some kind of attention deficiency disorder, so I need to be juggling three things at a time. I did not know that before – so felt unproductive, sad, and bored most of my life when shoved into the do-one-thing religion, which never fit. I also got very, very ill when I was busy, in a previous life.

Now I do lots of things, but I am not busy. I am occupied, but I’ll always have time for sleep, health, and happiness.

I am awful at calendaring, so I’ve hired a PA to help me do that. Calendaring makes me busy and sad, so I need to outsource that.

Today, there are a ton of things I’d like to do. There are always things to do. But I would rather focus on the meaningfulness of the things I have to do, rather than on the having to do in and of its own.

My to-do list might be massive, but I want to never close off my heart.

If I have to be insanely busy, which is a state I am getting to very rapidly, I want to be purposefully occupied, not and never too busy for anyone.

Invalid DateTime

I had one of those days today. The day when your to-do list is piled so high that you can't see the end of the tunnel. The day when your caterer cancels your big order a few days before Culture Kitchen. The day when all of your mega business problems are on the verge of getting solved, but almost. The day when you feel your heart pulling in a million directions, but there are no right answers, there never were.

I find myself having to lie down on a sack of rice quite often these days.

I work out of an office where the outdoor area has outdoor furniture made out of up-cycled gunny sacks. It's become my favourite place to sit on, to think.

A lifetime ago I used to travel around India by train. My dad would give me a sack of rice (minus the rice) so that I can lay on it in the sleeper class trains I would travel on, the ones without bedding or sheets or pillows. My backpack as my pillow. My rice sack as my bedsheet.

Waking up in the morning to find my arms imprinted: 100% Thai Jasmine Rice.

Today, I didn't have an imprint of anything. But I did sit on my sack for two hours. Trying to breathe.

Today, I fixed most of the problems, but not all. Maybe the day I fix every problem will be the day I find more to solve.

Why can't I be superhuman?

Invalid DateTime

Every morning, I get on a bike to work. Except I don't ride it. I bargain with someone on the street, or use an app to book one at other times. Do you want masker? They ask. It's the Indonesian word for face mask. Gak mau masker, makasih pak. Sekarang pergi ke Jalan Hang Tuah bisa? A string of words that I sometimes don't know I know, come out of my mouth. Every morning, I am on the road at a time when the entire city has already decided to get moving. I am in traffic. A lot. You can't miss it, really. I am not a morning person, but I am always thankful for this. This is being on a bike going to work in one of the world's most exciting cities at the moment for what I am doing. This is not having to stand in an MRT every morning for 30 minutes, packt like sardines in a crushed tin box. This is having difficult problems to solve, every single day. Being able to solve most of them.

I've never been one for job descriptions, but the only one that would truly work for me would be: "Adrianna Tan, Street Fighter". I find peace and equilibrium on the streets of noisy Asian cities. I know exactly where to find the things I need. I know where they are. If they are in buildings, I am not interested in looking for them anymore. If they are not wrapped up in an impossible puzzle, I don't know how to solve them. Somehow the best place to do any of this is precisely where I am, every morning: on the back of a motorbike, travelling over rubbish, driving by someone's wet laundry, turning out of a tiny alley before merging into the big city again.

I like this life. I like this bike. I like this city. The rest of it, we'll figure out.

Invalid DateTime

If it has ever occurred to you to start something, you know how lonely that can get. If you do that chronically, you probably over-estimate your abilities, have a high threshold for pain, or you're downright insane. The truth lies somewhere in the middle.

Welcome Drew Graham. Let's kick some ass.

Welcome Drew Graham. Let's kick some ass.

For almost a year, I did this alone. I started a company in a foreign country, in a language I barely speak (getting better at it), in the city of traffic jams.

It was hell. I would not recommend the 'sole founder' approach to anyone.

(Insert ten months' worth of whinging)

Yet every time someone asked, 'why are you a sole founder?'

I found my answer to be somewhere between 'because I haven't met the right person' and resignation. Singapore is not the Valley. Singapore is a land of risk-averse people who would pick a prestigious-sounding multi-national over plucky little companies, even if they paid them more. Singapore is a land of highly paid jobs, insanely high rentals and cost of living, so there's no wonder that few of us choose to make that leap. (Why do I do it? I started early, and there's no going back.)

Meeting the right co-founder is possibly harder than meeting the right life partner. You pull late nights, need to know you can count on them, eat with them, fly with them, drink with them, hustle with them, and generally spend more time with them than you would with your family. You even get haircuts with them (see pic above for co-founders' co-haircuts).

That person seemed, for a time, unattainable. :)

I'm happy to announce that today my friend and fellow hustler Drew Graham has joined me on my journey at Wobe, as my co-founder and all around hustler companion. Our plates are scarily stacked to the ceiling at the moment, possibly beyond, which can only mean great things are afoot.

Thank you for coming on this crazy adventure with me. I promise I'll pack two pairs of pants, maybe even a map.

May 7, 2015

I've been selling and hustling for much of my young life. I've learned loads from each part of it, no matter how small or insignificant it may have been at the time. I sold cable car tickets. iPod cases. DVDs. Button badges. Most things, really. In hindsight, they've come together to define what I do today. It's amusing to think of it, really.

Bookmarks

In my teenage years, I spent most of my vacation months hanging out in the Central Business District. Each day, I would sell (under the 34 deg C sun and extreme Singapore humidity) various items, ostensibly for a charitable organization that worked with destitute elderly people in Singapore.

I was 15. It seemed like a great way to spend my days{, and I made them between $10 000 and $15 000 a day, selling bookmarks to disgruntled bankers and lawyers (I was very good at it). Years later, we found out that the founder bought fast cars with the cash, which is why I now have a bullet point in my own charitable organization (we send girls to school in India)-"we travel by bus, train and economy class, and the only people who get paid are the people who work on the field".

Lessons learned: it was the first time I learned to sell the hell out of anything, and if you stand in the heat and sweat long enough (12 hours), eventually people will buy stuff from you.

Button Badges

With my brother Adrian Tan's help, I designed and made button badges. We ordered a button badge machine from eBay. We had different themes (his was punk music), I specialized in ironic and weird businessy/political/tech buttons.

People in Kansas seemed to like my buttons. A lot.

Lessons learned: there is great value in making. I wish I did more of that, and I will be trying to do more of it. Making something with your hands was the best experience ever for a kid of 15, and eBay at the time was revolutionary. It opened up a world of global commerce to me.

Etsy before Etsy

Whenever we went on family vacations, I would convince my parents to loan me a small sum ($100?) so that I could buy a bunch of 'craft' items from Bali, Bangkok etc.

I sold them on eBay for ungodly amounts of money because I would write beautiful copy about "handmade" and "artisan". In 2000. I truly believed it at the time.

I still have some of those photo frames, notebooks and paintings in my parents' house. When I discovered at the tender age of 16 that all of this stuff was mass produced, I felt I could not see them anymore.

Lessons Learned: having a product that people want is basic, but having a product people want and can easily access, is essential. eBay and PayPal opened that window, but good old copywriting was the secret sauce, and it continues to be for me in most of my businesses.

DVDs

At 17, I came to terms with the fact that I am indisputably queer. I did not panic. I did not freak out too much. I was not bullied. But I also had no idea what it meant to be a queer adult: I did not know any such people, and I did not see them on TV or in movies. It was 2002. I ran a "DVD ring" which distributed queer video content (not pornography!) to other teens who wanted to see people like us on screen. There was no Tumblr. The idea that queer people existed on screen was something that saved my life.

The movies were horrible, and I don't believe that queer movies have improved since. It was something I needed to do at the time.

Lessons learned: I cannot do the things that I don't love. I don't love queer movies, and I don't love incremental tech that aims to solve first world or Silicon Valley problems.

iPod skins and cases

In the first year of college (2004), I imported iPod skins and cases. I was loads cheaper than anything available on the market-I seemed to know what people wanted, and built the connections to make that happen.

Emboldened by my marginal success as a 19 year old, I wrote to Waterfield Bags telling them I would like to be their sole Singapore distributor. I had no capital, of course. They wrote back with a very encouraging note and walked me through the process of what I should have if I wanted to do that. I of course, could not garner the resources. But it was the first time that someone had ever spoken to me like an adult. As a young Singaporean kid at the time, most of my life experiences (outside of the home, which was a very progressive environment for me in every way) had been about the things I could never ever do because I am a kid and I am a girl and not rich. 10 years on, just a year ago, I would get on a motorbike and travel a distance to a tiny office in a Jakarta suburb, to bug somebody to give me the rights to sell rather hard to get. He would say yes, and it would become the basis of all of the work I am doing today.

Lessons learned: Don't pre-judge yourself. You are not weak, inferior, poor, or incapable because someone of where you come from or what you are. Action, like the act of reaching out and saying I will do this, does.

Macs

In 2004, I started selling Macs at one of the Apple retailers, and did so well I was featured in Cult of Mac and Scoble's blog, which brought me a certain degree of international / tech 'fame'. There are many people I know, still talk to, or have met, especially in the US and in Europe, because of these early international tech links. In many ways, every aspect of my adult life has changed because of the years I put in selling computers and iPods. That I run around doing crazy businesses, Steve Jobs 2005 Stanford commencement speech. Learning to sell the shit out of anything, standing on my feet for 8 hours a day. And I mean anything.

Through my time walking the fertile grounds of Mac stores selling thousands of dollars of hardware a day, often to the extent of forgetting to eat, I developed a loyal clientele of high net worth individuals to whom I became their personal technician. That put me through 4 years of relentless backpacking throughout and after college. I encrypted emails for mining tycoons. I backed up data (there was no 'cloud' back then!), retrieved data from corrupted hard disks, ran around with bootable flash disks with installable OSes and data retrieval utilities in my wallet. I had a FireWire cable in my pocket most of the time. I took apart hardware, put it together, and somehow never had enough screwdrivers. They paid me well for it, and they taught me about charging for what clients should think I am worth, rather than what I thought I was worth, which at the time was, not very much. I got to see every single Southeast Asian market extensively, traveling on $200 for a month (how did I do that?), learning to stretch my dollar. Being a part of the Jobesian / Apple meteoric rise and return in that period changed everything about my professional and personal trajectories.

Lessons Learned: hustle hard, and do it well; people in general will not take advantage of you. "How much will it cost for the 7 hours you just spent taking stuff apart for me and saving my data?" "Maybe $100?" (Remember, I was 19…) They would laugh and say, here you go. And hand me $1000. It taught me that when I am in a position to reward a young hustler, either financially or in terms of opportunities given, I most definitely will to pay it forward.

When I was in the middle of all of that, people constantly asked: why? What good does it do? Why are you travelling around India or Indonesia for weeks and months and living like a hobo, instead of taking multiple prestigious bank internships?

Somehow, I had the weird feeling that it would all make sense. It has only just started to (and it's not like I did shabbily in the time before). I quite simply chose a different path, not because I had so much conviction and talent, but because to me those paths were the only ones open to me.

I'm so excited to see what the next 10 years will bring. I've spent the last 6 months living in Jakarta, building Wobe and getting to learn every single day about the wonderful place that is Indonesia. What I have now, which I did not have before in my formative entrepreneurial years making buttons and selling DVDs, is a team of hugely amazing, talented, and most importantly, good people, who I have the privilege to lead. Teams are everything.

I've come to see that these insane plans of mine did not come out from a vacuum. I did not just sit in an office one day and decide, "I should get into (insert generic type of) business". They came from sitting in a 36 hour bus rides talking to people in languages I don't understand (Turkish and Arabic, for example), building and making all kinds of crazy products with all types of crazy people (I once built a website for a West African airline, but they never flew because their leader was deposed to Burkina Faso).

They came from being told several times a day that I could not have something because I am a girl, a foreigner, or just plain unlucky. A train, a bus, a business opportunity, but having to figure it out anyway because sometimes… you just have to.

One morning in 2010 I got out of a train from Aleppo, and found myself in Gaziantep, a border town between Syria and Turkey. The problem, as I soon found, was that I had no euros or Turkish lira. I did not have any money except worthless Syrian money. There was no ATM at the train station. I was, in short, screwed. Experiences like that have been far more difficult than anything hard about the hard in "it's so hard to do business in Asia".

(I managed to barter a ride to the next city.. I think I traded a Turkish kid some notes and coins 'from the Far East' so that he would buy me a $1 bus ticket!)

Experiences shape you. My formative entrepreneurship taught me about payments, exchange rates, marketing, making, selling and most importantly, customer service.

The time I had to sleep on the dust outside Trichy airport (long story), when the auto-rickshaw I was driving around South India broke down on an unlit hill. The many times on the road in which I've had to deftly worm my way out of extreme sexual harassment. All of those experiences are starting to make sense to me now.

I probably spent less on all of that over the past decade than I did on getting a degree. As a child, the stuffy classrooms in Singapore that I sat in and the theoretical problems I worked on, may have formed the foundation for many other things. I learned about hard work, and I also learned about dogged persistence there. But if you told me that all of my childhood dreams, inside those classrooms, looking out into the world and dreaming of a life on the road, doing things in the world, outside of a four-walled environment, that all of it would come true and that reality would be even better, I would not have believed you.

Thank you to all the crazy ones who believed in me enough, some of you even enough to come along on the ride with me. I pack snacks and biscuits, and two pairs of pants.

Invalid DateTime

There's a wealth of literature out there about this, but it can never be said enough. Too many people work with assholes.

You see them everywhere.

The cafe owner that takes a shortcut by hiring an asshole barista? The barista plays shit music at your cafe and nobody wants to go there.

The startup founder who values talent over attitude? The asshole co-founder or top exec, no matter how good they are at their jobs, is going to screw you over.

Eventually you realize that you're losing money and that nobody wants to talk to you at industry events anymore. Or perhaps investors or future team members take you aside to say they want to be a part of your dream team, but… that guy is an asshole.

Assholes don't inspire trust.

Assholes can sometimes be nice, too.

People often make the mistake of assuming that the opposite of an asshole is a push-over. It is not. The opposite of an asshole is a decent business-person or partner who brings net positives to the table. An asshole, no matter how occasionally nice, perhaps to certain people, or to most people, has certain characteristics which breed mistrust and disdain.

At my first startup, I worked with a guy who was a really nice person, and very good at his job-to me.

I was new to the scene. I had no idea.

He had ideas, he got things done, he was a good person-to me.

But he was not a good person to people who could not give him something.

There will always be people like that.

I'm talking to a handful of investors at the moment and what I do for each one is to see who has worked with said people before. I call them, no matter how tenuous the link, and say: "What do you think of ____?"

You don't really have to get more specific than that.

You can, of course, to clarify some of the assumptions that people might have made, or to get more details on deals gone sour, etc, so that you can make up your own mind.

But I've found most often that if I am going to be met with silence or awkwardness or worse, with hemming and hawing which can seem unjustified, it's a red flag for me.

This applies to people I hire and to people I date, too.

You need to be sure that this person doesn't kick old ladies or torture pets when you're not looking. A good way is to see how they treat waiters and how they respond to the homeless or the poor.

I don't need you to be a bleeding heart old lady hugger (please don't), but life's too short for anything that isn't "fuck yes, yes and yes".

No amount of money is ever worth it. That's not idealistic-it's the most practical advice I was ever given.

Invalid DateTime

Some time ago, some people (read: entrepreneurs) I follow on Twitter posed a seemingly innocuous question. What drives us, as so-called entrepreneurs, to do what we do? Is it hubris? Ego? Is it an out-sized and unrealistic view of one's abilities? For most of us, choosing this life also means the opportunity cost we left behind, often reluctantly: decently-paid jobs with career growth at startups, VC firms, tech companies, banks, even… bars. There has been no better time to be a tech exec. My friends, and I am sometimes envious of them, clearly smash through the income and lifestyle brackets in the top 1% of the cities they live in, even the world-what we do is such a upwardly mobile trajectory. The lifestyle, with the stock options in soon-to-IPO companies, global travel as part of international "launch teams" in the most successful tech startups, fuelled by the globalizing of venture capital and focus of said capital in my part of the world, is certainly tantalizing. No longer do you need to work in finance, it seems to say, with each job offer and recruitment mail, in order to eke out a nice life for yourself and your family. The stock options certainly don't hurt.

So what can it possibly be that some of us choose to do this? Even though it's easier than ever before to raise money and do your thing, the fact is no matter where in the world you do this, building a business is just terrible. It's fun, otherwise we wouldn't be drawn to it. It can also be rewarding, otherwise we wouldn't try. But. It's hard.

I'm torn:

Between the deluge of entrepreneur porn articles and this shit is hard articles (like this, but 10x more pity): I'm torn.

On the one hand, having the ability and the opportunity to start and run your own business, even to try, is a damn privilege. It really is.

On the other, there are so many moving parts. Skill sets you need to suddenly and abruptly become a ninja at. As a founder, from HR (super important) to project development to technical skills to payroll to accounting to taxes to… whatever challenges it throws at you, really.

The last couple of weeks have super hard.

Stressful.

Energizing.

Insane.

Gut-wrenching.

Incredibly amazing.

Many startup founders come across founder depression at some point, and I think it's a real risk you expose yourself to when you put so much of yourself on the line. No matter how well-adjusted you think you are, you need all the help you can get.

This is my second company. My first, right out of school, was a dev house that specialized in creating innovative marketing projects for advertising and FCMG companies through the then-new mobile and social platforms.

Pushing 30 this year, doing this at 30 is a world apart from how it was like to do this at 22. I'm sure there are many young startup founders who learn and grow on the job, or perhaps possess a certain self-awareness and ability which I did not have. But. I find myself, this week, making dozens of decisions daily-on the sorts of things which would have caused me a lot of grief, time, money or existential angst, back in the day.

I have the opportunity, the right teams, and the business partnerships to push through with the sort of tech business I have always want to do: tech, finance and social good.

Now?

Now, we ship. And learn. And ship again. And learn again.

I love it. I hate it. I love it.

Invalid DateTime

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was a bit of both, really.

I'm not one for the mumbo-jumbo of the Myers-Briggs test, but I suppose it was striking that when I did it before my startup I rated very strongly as INFP, and yet now I'm very much on the ENTJ spectrum. It appears that having to do shit in a prompt, aggressive way does bring out very different approaches.

So, startups are hard. You already know that.

In my case, every attempt to think that through inevitably ends up being a little self-pitying.

How and why did I decide that leaving my family, and puppy, coming to a foreign place, to work on some problems involving the silos of payments, mobile, commerce and gender equity, was the best life and career decision of all?

Yet… I wouldn't have it any other way.

Yes, I know the rates of failure are high, in any startup. Not to mention one with foreign laws, language, culture, and way of life/business.

Yes, I know that there's only so much hustle can bring you. There's also the regulations and expectations of archaic industries and economies in certain countries.

But man, it's exhilarating. If shit hits the fan and nothing goes the way we intend despite the best laid plans of man (and woman), then at the least we can say that I now have very specific knowledge and connections in some fairly obscure Asian markets.

It was a brutal week.

I lost a kid in the community my foundation does a lot of work in. She was 14. She had dreams. She was vivacious. Perhaps, her undoing, in an unforgiving climate.

I lost a key team member. To the same brew of inexperience and lack of discipline and foresight. But team before product, and it's never going to be easy.

Also, some huge gains. Solved some massive business obstacles. Created some solid partnerships. Brought in many valuable individuals to build the team. Net-net, a good week, if a little brutal.

There's shit to do and a world of problems to solve. A glut of solutions we can create and design, and hopefully do so beautifully, with elegance, sensitivity and impact.

In late 2012 as I stood on a similar crossroad contemplating major life decisions, mostly relating to the geography and type of work I wanted to surround myself with, I found tremendous opportunities, but I also found my heart had already decided.

My 30s are to be spent in my backyard. In Asia. In the emerging markets of Asia. Doing as much insane and crazy shit as I can possibly throw at it. I feel honoured to even have a single shot at it.

I am.

It was the best of times, and the worst of times. Ask me again some weeks from now. Months. Years.

I think I will say that there's nothing else I would rather do, and nowhere else I would rather be, than here in the heart of Java, toiling for a dream.

Coconut makes the world, and our infra, go round.

Coconut makes the world, and our infra, go round. Dark, golden and distilled beauty. Just like our microservices.

Dark, golden and distilled beauty. Just like our microservices.

My total, with the unique code (+032) added to the final bill.

My total, with the unique code (+032) added to the final bill. “

“

Welcome Drew Graham. Let's kick some ass.

Welcome Drew Graham. Let's kick some ass.