Some thoughts on being a gaysian immigrant to California

Two weeks ago, I helped to plan and organize a Lunar New Year dinner for 120 queer and trans Asian people. It's a tradition that has been around for as long as I've been alive: the annual APIQWTC Banquet.

Despite its mouthful of a name (much easier if you read it as API CUTESY Banquet), it was an event that left me feeling extremely raw and emotional at the end of it.

I could not identify why exactly.

Could it be that these events—large format Chinese dinners I've only experienced in the context of societal rejection—were usually events I hated, events that were milestones I can never have because I was gay in a country that had not fully accepted it? I was never going to have the large Chinese wedding dinner. Even if I think those are horrible, it would have been nice to have known that was open to me.

Or they'd be a celebration of some kind of matriarch or patriarch, the sort of thing where your same sex or trans partner was often excluded from, unless things were Very Serious and they had already graduated into the Don't Ask, Don't Tell territory. At some point, people get old and it becomes possible to welcome same sex partners into these events: when you're old enough that you're thoroughly de-sexualized, is my guess.

But there's more, beyond mere social acceptance and the idea that it's possible to have a good time, I keep coming around to the thought: if I had been to such an event, if I had known these people, when I was a teenager struggling with my feelings and my identity, my life would have been different. Visibility in the media is important, and I already didn't really have that back then; but visibility in the form of knowing that it's possible to grow old, screw up, fall in love, get divorced, have children, or not, organize community events and be an advocate, or not, all of that would have been powerful visual indicators to me that it's possible to have any kind of life. That you're going to have a life at all.

Instead, growing up mainly among an older generation that was largely forced into the closet—and I do have strong memories of going to gay bars for the first time as a teenager that had just come of age, and seeing police raids rounding up gay men for 'vice', more than once—where the only people I knew to be gay or queer for sure were the advocates who were willing to put themselves out there to fight for our rights, document our stories, to tell our homophobic society that we exist. Those people served a purpose and they fought bravely. But I did not always want to be an activist. Even though eventually, I guess I sort of did.

By simply refusing to pretend to be straight, at some point I found myself thrust into a position of hypervisiblity in the queer community in Singapore. I did not want to be that person. I simply wanted to write about the heartbreak I had endured as a teenager: I was just the queer equivalent of a teenager anywhere Live-Journaling her heartbreak. But by not changing the pronouns of the person who had apparently broken my heart, I became, I suppose, a queer activist.

I did not know any queer couples or families until I was well into my early 20s. Other than the women I dated, and let's be frank, we were a mess, with no template or model or idea of what any of this was going to become. Information about queer people came into Singapore like a trickle: there were the gender studies books at Borders bookstore, the 'are they or aren't they' gay-guessing games of trying to figure out which celebrities were queer women (hint: it was mostly Angelina Jolie, at that time), I didn't really know what it meant to be queer. And I think I was already an extremely well-connected teenager for my time. (For a time, I ran a queer DVD lending library; I'd distribute movies and documentaries to other queer teens in my high school and elsewhere.)

I did not know what it meant to be a queer adult.

I had no idea what it meant to be in a committed relationship. Or what it meant to not be in one. I didn't know what my life was going to be. It was all a big blank, other than 'I guess I will have to go live overseas some day'. Even though Singapore has, anecdotally, a fairly large queer population, information about queerness is still suppressed by the state. We are still not allowed to see, for example, a reality TV show of a gay couple having their house revamped. It would be against the rules: you simply can't portray queer people in a non-negative manner.

So when I found myself surrounded by a hundred dancing Asian queer aunties, and a few other peers and younger people, I was mad.

I was mad to not have been exposed to the idea that I too, can some day be a dancing Chinese auntie in my 60s, prancing about on stage singing Teresa Teng songs at a karaoke in Oakland. I was mad that I never got to see people like M and her partner, an older interracial East- and South Asian couple, like Sabrena and I: with their children babbling about in several languages, the way it might look for us if we decided to have children some day.

Most of all, I was mad to know that this life wasn't possible for me back home. Not by a long stretch. I hardly knew many queer people in my mid 20s, and I definitely did not know that hundreds of queer people above the age of 60 existed. Nor did I have the chance to meet them in a multi-generational setting, the way I did here.

At the event, I met many people who were also immigrants from Southeast Asia like me. The first decade was hard, they said. They had to figure out how to exist in the US, and it was also at a time when the US didn't even have the laws it now does for same sex marriage. Many of them wouldn't have been able to move here or stay on here even if they had American spouses: not until Edith Windsor did us all a favor and defeated the Defense of Marriage Act, and enabled same sex marriage and other rights at the federal level.

In that regard, I have it a touch easier. I came here for a high paid tech job, I came here when California is already one of the easiest places to live in the world for a queer person, and I was able to bring my spouse with me. But some days are harder than others. Like many of these aunties, I am dealing with my first decade blues: does it ever get better? Why did I give up my life of privileges and comforts in Singapore for.. America? Unlike many other immigrants, I did not come here for economic or material improvements. I came here for far more abstract things, like 'my rights', but also for very concrete things like, 'my wife and I need a third country that recognizes our marriage so that we can actually live together somewhere, anywhere.'

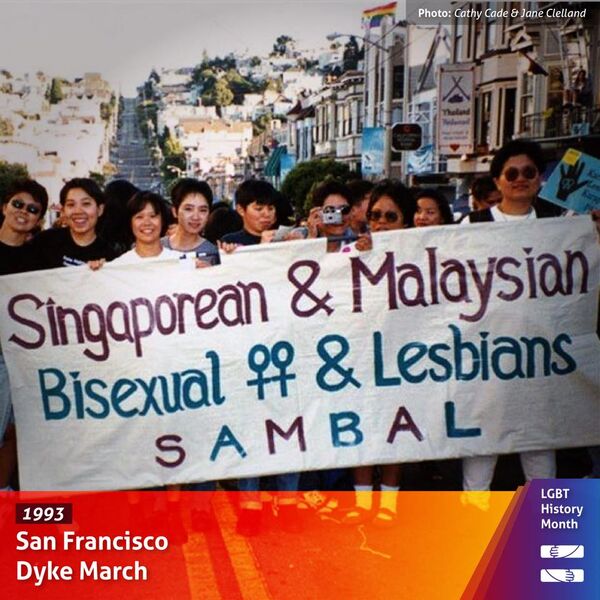

A few months ago, I saw this image again: it was an image of Singaporean and Malaysian queer elders in what is clearly San Francisco, in 1993. I reached out to a few of them in the photo to ask: what was your life like? What did you struggle with? What's your life like now? Many of them said the same thing: the first couple of years are very, very hard. Some days you wonder if you will ever truly feel at home here. But, they said, we now have wives and lives, and that's more than we could have expected of our lives in Singapore and Malaysia.

Wives and lives. I have that too, but I also have had far less time than them in California. I still have one foot in the door; I am still not totally removed from existing in a space where I've had to hide myself, and my life. Even the most hyper-visible ways of being queer back home are just standard, everyday ways here.

One of them said, my wife is organizing this banquet, why don't you get involved? And so I did. I still don't have the answers, but I think I am starting to have the inkling of an idea.

I think it looks like dancing on stage at a Chinese restaurant singing a Teresa Teng song. I think it could be carrying an infant babbling in three languages. I think it might be nice to have the ability to work with younger Asian queer immigrants 25 years from now, who will hopefully have an easier time than all of us did. I think it could be fun. I think I have a life ahead of me of queer joy that I can celebrate.

I can be anyone I want to be. I did not always know that.

(Photo taken on a Minolta Hi-Matic 7S II, shot on Kodak 5222 film, self-developed in Rodinal 1+50 at ISO 800, and scanned on Plustek 8200i. For more film photography shenanigans, check out my film photo blog)

Going to the mountain.

Going to the mountain.