Posts tagged "life"

← All tags

January 5, 2024

- In 2023, I got to explore a whole year of creativity, namely in film photography, photographic darkroom printing, piano and saxophone-playing, and drawing

- Film photography felt like an old friend I was coming back to: I was already shooting film 20 years ago, but dropped off for the digital world

- In moving to San Francisco, I also found a community of film photography experts and enthusiasts around whom I could build a creative practice

- It's much easier to continue pursuing a hobby when there are events to attend, people to share, and spaces to go to for it

- I crossed off the vast majority of items on my learning wishlist for photography: I learned to bulk roll film, I learned to shoot medium format, I learned to develop film in all processes, I learned to scan film and also print (in a darkroom, and digitally)

- I'm now reasonably confident in all of those things, enough for me to be able to print photos for art shows

- Not sure where I want to go with the printing thing, but it came in handy when I also, in the last two months of the year, started teaching photography at a community space in my neighborhood

- I gave disposable film cameras to participants (who are either unhoused or who mostly live in the supportive housing in the area), who then went forth and took photos of their lives and experiences

- A local film lab helped us develop the negatives, and I printed out a selection of participants' photos for a small private art show at the community space. I am now working on documenting and showing some of this work online and will share it when I am ready!

- In developing a 'creative practice', I've come to see that the work I do in photography or in music (or even meditation) all have similar roots

- It's all about establishing a regular practice on something in my life where, maybe I won't ever be a professional, but it's something that I personally really enjoy and can learn from

- It's enough joy to be able to work on these hobbies that bring me peace and solitude

- When I sit in a completely dark darkroom, that's one of the only times I am away from a screen

- The hour or three that I spend in one helps me center my thoughts around creating something beautiful that can bring happiness to someone else (my wife, for example, really likes having prints so she can decorate our home with it. I also love giving prints to friends)

- Given that I stepped away from photography for a decade or so because I was burned out by the practice of commercial photography, which killed my love for it and which also made me uninterested in picking up a camera for a very long time, I'm very happy with... this, whatever this is!

October 3, 2023

I've learned a few new things since I last posted about how other Singaporeans can apply for, and receive, the H1-B1 visa.

In renewing my visa in Singapore this September, I opted for the new-ish interview waiver process (available since 2021).

Although I have never had a rejection, going to the US embassy is always a stressful time. You see so many people (usually non-Singaporeans) getting their work or school dreams dashed at the window. You can hear everything. The high stress, high security: I would very much like to never go there again.

The interview waiver process was made available to me at the last step of the visa application, in the USTravelDocs portal. When scheduling step 6, USTravelDocs will ask you a bunch of questions to determine if you are eligible for the interview waiver.

The main thing to note is that only Singaporeans and permanent residents are likely to be eligible. While the main applicant for H1-B1 has to be a Singapore citizen, if your dependents (spouse or children) are not Singapore citizens, then they will not qualify for the interview waiver. Definitely allow more time for an embassy interview if that's the case.

I was nervous about whether or not to do this, so I consulted a Singaporean immigration attorney in California. Junwen was able to give me very specific advice that I found helpful. Check out his blog here. I highly recommend booking an appointment with Junwen (send him a message on LinkedIn) or use this contact form to email him if you have any specific questions (paid consultation).

He advised that I should use the Chinatown document drop-off point at Bstone Travel, instead of the Changi location. This is because his clients had some challenges with the Changi location recently, which led to delays.

He also informed me that the interview waiver process can take anywhere between 4 and 11 days.

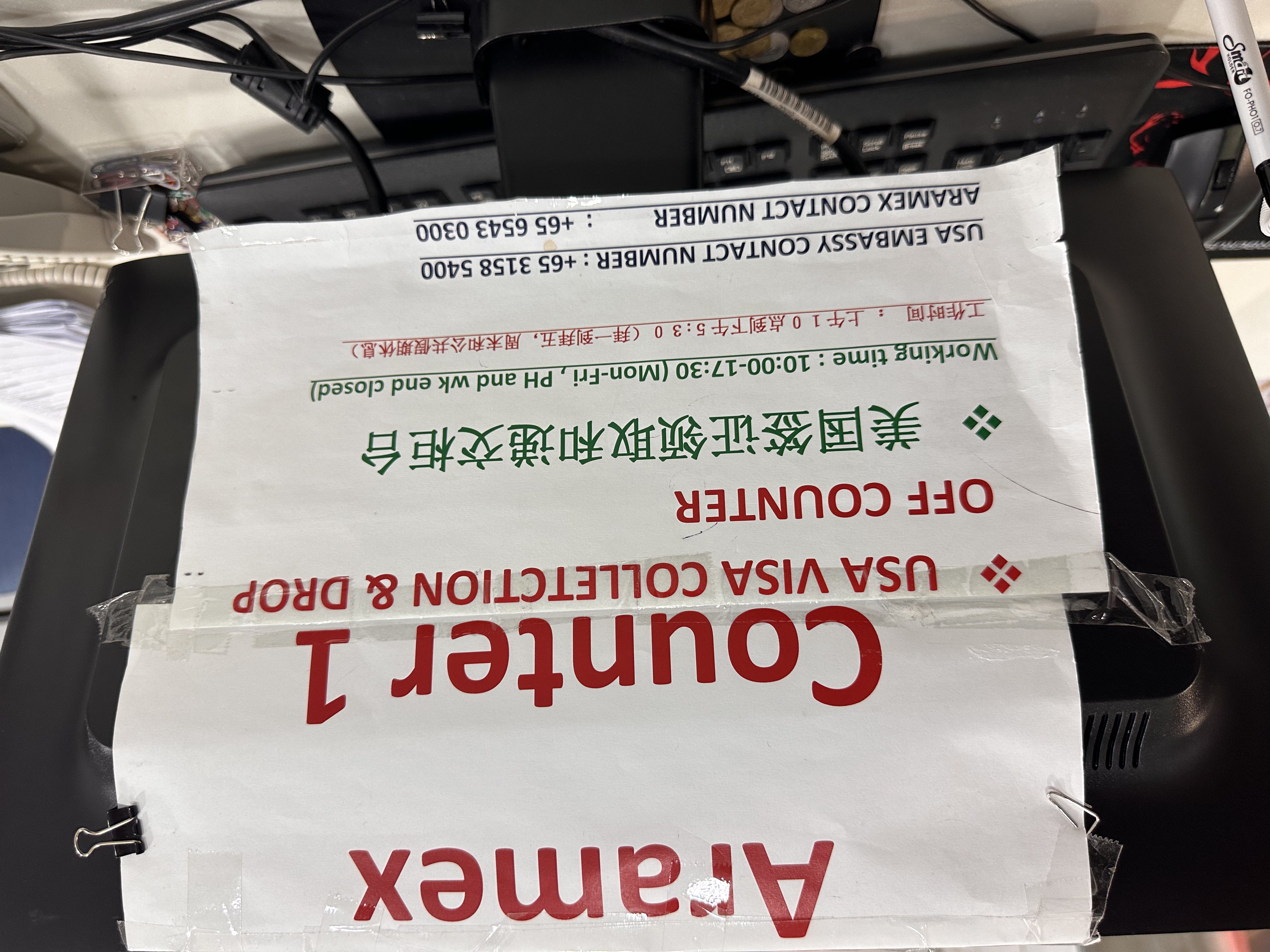

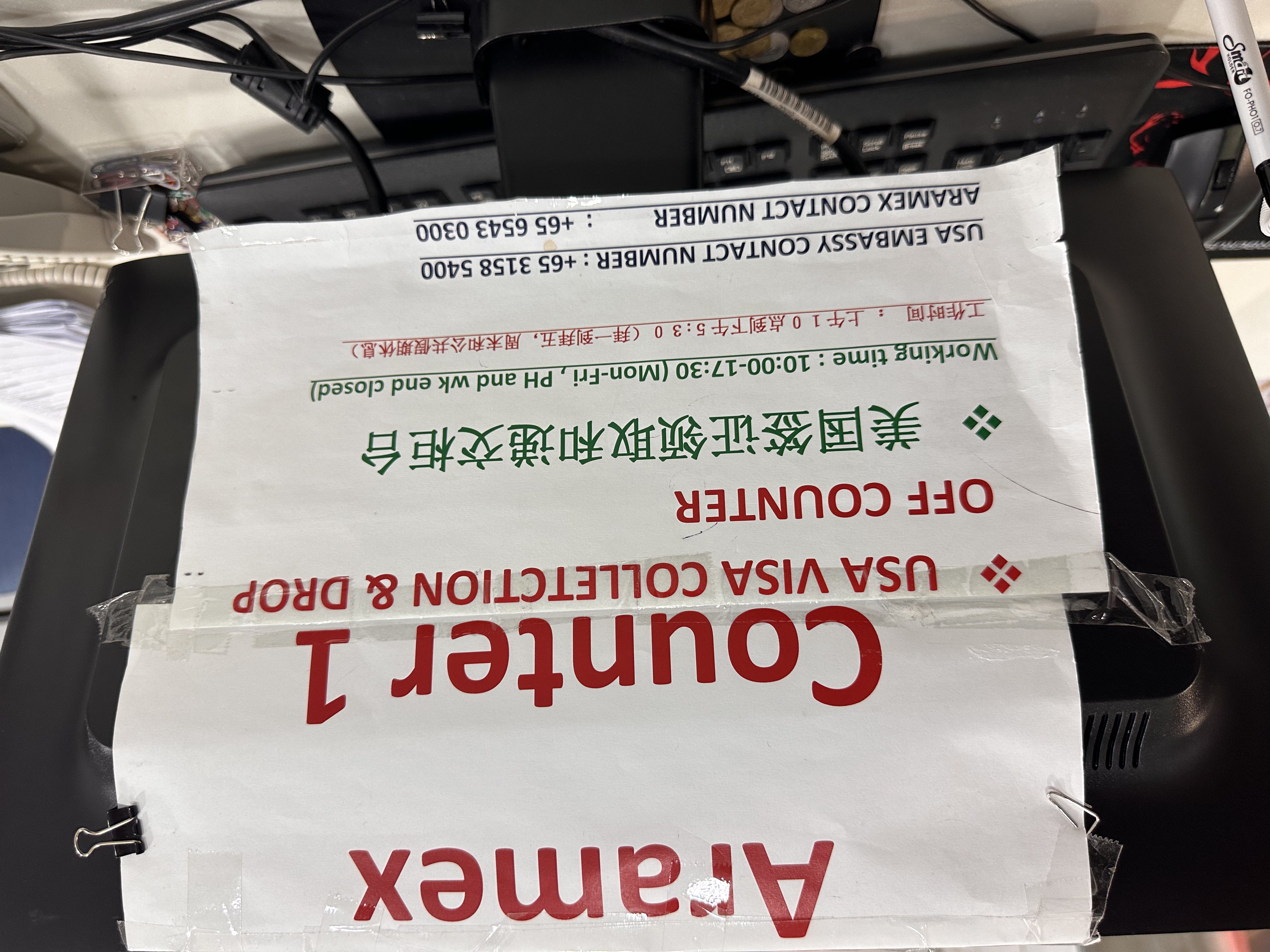

Document collection and drop-off point

#

Because I find the USTravelDocs so ridiculously difficult to navigate, I am pasting this information here for anyone who needs it.

Check that the information is still accurate before you rely on it though, I may not be updating this page with new information.

- Aramex at Chinatown, located at Bstone Travel, People's Park Centre, 101 Upper Cross Street, #B1-31, Singapore 058357

- Opening hours: 10am to 5.30pm, Monday to Friday

- Closed on Singapore public holidays and weekends

- US Embassy contact number: +65 3158 5400

- Aramex contact number: +65 6543 0300

The email you will receive about dropping off and collecting your passport / visa says they open at 11am, but they actually open at 10am. At least, they did, as of September 2023.

Interview waiver timeline

#

- I dropped off my documents (passport, signed LCA, interview waiver confirmation code generated by USTravelDocs, and passport photo) in Chinatown on a Tuesday afternoon around noon.

- I checked the visa status tracker every day and did not see any change until Thursday, when it changed to Approved

- On Friday, the status changed to Issued

- On late Friday night, I received a text message saying that the passport will be available for collection soon

- As all the document collection points are closed on weekends, I didn't hear anything else until Monday

- On Monday morning, I got an email that my passport had been sent to the pickup point (the same place I dropped off my passport)

- On Monday morning, I joined the line at 10am (although Google Maps, and the email you get, says it only opens at 11am), and got my passport in 15 minutes (there was a line)

Excluding the document pickup and drop-off days, it took 3 working days in all. Maybe dropping off on Monday first thing in the morning would have been faster, but I wasn't in a hurry.

It wound up being almost the same as going to the embassy in the past: if I went on a Tuesday, I would have received my passport on a Monday morning anyway.

So I got to do that, but skipped the anxiety and stress at the embassy. Highly recommended. Just make sure you have ample time in your travel plans.

September 27, 2023

Tretes, Indonesia (link to some photos I took

- I have been struggling with my feelings on and about immigration.

- Some time in mid 2023, a woman at a bus stop in San Francisco pointed a blow torch flame at me and threatened, I'm going to burn you, because you're Chinese!

- Number 1 is possibly related to number 2.

- A theme I keep coming back to: why does it feel like this?

- The feelings: neither here nor there, a deep sense of longing for 'home', uncertain what 'home' really means, feeling like I'm in two or three places at once, feeling stuck, feeling like I don't know where I fit, feeling like I am two people at once.

- That the 'home' I return to, I no longer fully fit into. I left five years ago, and in that time: obviously, it's moved on without me. I no longer know how to exist here in Singapore. I don't have any routines, I don't have places to go, things to do. I'm no different from a tourist. Just that I'm a tourist who knows a lot of details about this country, and who has an intimate knowledge about its food and its politics.

- That the 'home' I now exist in: where I have work, family, contemporary friends, hobbies, a home, feels on some days like it's real and solid, and on other days that idea of solidity is completely unraveled, especially when things like number 2 happen.

- I've spent the past week in Singapore and Indonesia. It's been splendid to be around friends, food, the weather, environment and culture that I know and love.

- A big part of why I suffer from number 1 is that I feel completely estranged from the Southeast Asian bits of my life when I am in California. I can probably fix that by going to do things like, I don't know, play gamelan or learn Balinese dance in Berkeley (both activities that are very popular and established, led by East Bay Indonesians).

- Living in the heart of the imperial superpower, I do not hear, see, learn about anything about the outside world outside the US at any time. TVs don't play world news, they play sports: sports that only Americans play. Online discussions tend to veer towards only domestic politics. I feel like I'm at the heart of the world, and totally cut off from it, at the same time.

- I've fought it for a while, but I feel the semblance of a nascent Asian American identity forming. Ever since I learned about the Hyphenated Americans discussion, I've been far more open to the idea that without the hyphen, I can be both Asian and American (without necessarily needing citizenship).

- As number 11 strengthens and solidifies, number 1 also waxes and wanes. Some days, I am convinced that coming to California was the best idea I ever had. On other days, I cry myself to bed missing tropical weather, my family back in Asia, immigration stability (not having immigration challenges at all), and maybe a romanticized idea of what Singapore means to me.

- The past week in Indonesia was transformational. Not only did I get to wake up the part of my brain that had been dormant for a long time, the one that speaks, understands, and exists in Bahasa Indonesia as well as Bahasa Gaul, I also got to reconnect with my friend of 25 years.

- Beyond the food, which was amazing (East Java has my favorite Indonesian cuisine and dishes), it also sent me down a rabbit hole of listening to Indonesian music and reading in Indonesian.

- I was reading something today that referenced the idea of merantau cino.

- I know about merantau: it's the Minang rite of passage where men leave their homes in Sumatra to pursue careers and experiences outside their village. There was even a martial arts movie made about this.

- In merantau, the idea is that you leave and then you return to your home.

- However, in merantau cino, you leave your home and you never return. Not permanently, anyway.

- The term is based on the idea that the southern Chinese diaspora left China, many of them never returning.

- Therefore, a person who does merantau cino is doing a rite of passage, embarking on a migration story, where it's unlikely that they will return to their original homes.

- I'm not sure whether I am a perantau cino or a merantau cino yet (difference explained here; article in Indonesian), but I'll be damned if this hasn't been a more relevant and insightful observation about my personal immigration journey than anything I have read about in English, in an American context.

- When I get 'home' to San Francisco next week, a couple of milestones will happen; things that will set us up for a different phase in our lives there.

- I will probably always see myself as someone split down the middle.

- Two lives: one here, one there.

- But at least I know now that there's a name for it. And maybe it feels a little less lonely, since merantau cino was exactly what my grandfather did, as a teenager.

September 7, 2023

Citizens of some countries need a visa to enter Singapore. If you have friends or family that belong to those countries, you can do them a huge favor by applying as a local contact.

As long as you are a Singapore citizen or Singapore PR with SingPass, or director of a Singapore-registered business, you can help your friend get a visa. Please make sure that you actually know this person!

I only do this for people I know.

It can save them a lot of time and money. Most of the time, I do this for my friends from India. It's much faster and it also costs less than them going to a visa agent.

The following instructions are for Singapore citizens and PRs who have SingPass.

- Before you start, send this PDF form to the person you are applying for the visa for

- Ask them to write down the answers to all the questions in a document, and send it to you. Also ask them to attach a passport photo in the right format

- Visit this ICA page and click on "Apply for a an entry visa as a local contact (Individual Users)"

- Log in with SingPass

- Click on "Individual Visa Application" to apply for 1 person, or "Family Visa Application" to apply for more than 1 person (they must be married; children above the age of 21 must have their individual applications)

- Fill in the form according to the information your friend provided you. Be sure to get their birthday, passport issue date and passport number correct.

- Upload their passport photo

- Pay: you can pay with American Express Cards, PayNow, or eNets (internet banking).

Save the application as a PDF. It will take 3 working days to receive a response, but in my experience it has been usually faster than that (next day has been the norm).

You can look up the status of your visa application here.

So far, I have applied for friends from many countries and I have not received a single rejection.

Please refer to ICA's own documents for screenshots and more explanation for each step. These are all PDF files:

June 9, 2023

With my wife Sabrena in the Paris metro in 2022

With my wife Sabrena in the Paris metro in 2022

1993: I am 8 years old. I am a scared little autistic girl who felt in my bones that there was something strange about me. Was it my obsessive, hyper-fixation on the things that interested me? My intense feelings? Or that I felt I had to lie every time the other girls shared the lists of 'boys they liked'? I often felt like a child who had so much to say, but no words at all. The words that people used with very young female children did not feel right. 'What boy do you like?' 'What kind of man do you think you'll marry?' 'When you grow up and have a family...'

None of that ever felt right. I didn't have the words. Instead, I said things like 'I will never marry!' Which made people laugh. Of course you will, they said, you will meet a nice boy and you will marry him. 'I don't like boys!' That made people laugh even more. No one believes what children have to say unless they fit a script. I didn't have any of the right scripts.

I did not know any queer people; the only time I ever heard about gay folks or trans folks was on the media, in a derogatory manner. I was about to use the Internet for the first time, and that would change my (whole) life. The first thing I do when I go on the Internet is to look up whether or not women lived together abroad. I find a lot of information about not telling anyone in the military that you are queer. I go on IRC and message a stranger and ask, 'how does it work?'

I don't feel guilty in church the next day. I just feel like I know the biggest secret of the universe, like there's a name for people like me, other than pervert. But I worry about the logistics. How will I find a wife? I imagined I would have to fall off the face of the universe and disappear forever to even do that.

I spend the next six years at school writing stories about stowing away, disappearing off the face of the universe, sneaking off to start a new life as someone else.

2003: I am 18 years old. I have dated both boys and girls. Sometimes, at the same time. I give myself an arbitrary deadline. I want to decide at the end of high school which I prefer. I know that 'bi' exists and that's what I thought I was, but it didn't feel like me. I decide I want to start university with.. certainty. All I know is that boys are straightforward and easy, and girls are not. I know deep down I never choose the easy, because that rarely interests me, and I know I am at the fork in the road where nothing is going to be easy from now on.

2013: I am 28 years old. I have a 4 year old dog, Cookie. We live in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. My first long term girlfriend got her for me, or with me, I'm not sure. 'If we ever break up you're going to have to take her,' she says. I have just been diagnosed with a terrible autoimmune disease, and she has to drive me and Cookie 350 kilometers to take me home. I've had to move home after years of 'gallivanting' all around the world, as my family would say, and I am learning to be at home and be at peace for the first time. I am out. I am going to live in Singapore for the first time as an out queer adult and single person. I am alternately sick and alternately learning how to be single again. I am sicker than I think. I go out with a different woman every week and I feel like I can be more openly queer at home than I ever imagined, but I also feel an impending doom: I was tired.

Tired of running the race with a potato sack tied to my foot). Tired, generally. I do the unthinkable: I move out of my parents' home within months of getting back. You're not supposed to do that until you marry (a man). "You don't want to be here when I am dating all these women, do you?" I imagine myself saying. I think I say something to that effect, but dialed back. I am always dialed back at home. I can be 'a gay', but I should be proper. I can be 'a lesbian', but I should be successful. As long as I am successful, people are fine with me being queer and autistic. But it should always be in that order. I am reckless with the hearts of the women who apparently love me in this time, because I don't feel like I deserve to be loved.

2023: I am 38 years old. I now live in San Francisco with my wife, Sabrena. Our dog Cookie is 14 years old. Mila, the large tortoiseshell cat we adopted when we got here, is 17. I have the queerest, most autistic life I can imagine, here. Three days into Pride month, I've already met and spent time with mostly queer people. They have lives, careers, families. Like me, they also came here from somewhere else to live their queerest, and sometimes most autistic, lives. From Montana. From Sarawak. From Singapore. From Taiwan. From China. For many people like us, California is a refuge. I have been here for five years now. It makes me sad that a country where neither of us have citizenship recognized our marriage, and gave us the ability to exist, survive and thrive, in spite of our sexuality, when our own countries tell us we are broken. And I am proud that our state gives us the opportunity to live our lives, as our most queer, most autistic selves.

But when I brush up against elements of my old life, I am annoyed. I don't believe I should wait for gay men to have their rights first and then advocate for other's. I don't believe trans people should wait their turn in line to stop being discriminated against, especially in this time of trans genocide. I don't find it acceptable to have government officer shout that my marriage is not recognized in Singapore when just last year I helped to review a form for another government that said Person A and Person B instead of "Husband" and "Wife". Friends from home say I am now too loud, too American, too... different. It's probably true. I no longer have it in me to allow another person, institution, organization or government to pretend that I should not exist. I don't have it in me to be okay with not having any rights anymore, either.

We're here and we're queer, we're also very autistic (which is related) and we are very tired. I am very glad, however, that I did not have to disappear off the face of the universe to find a wife. Take that, 1993.

February 23, 2023

Various things in the last few years have alerted me to the terrifying fact: I don't think I had an attention span at all until, well, now.

That I was able to graduate from college, get married, hold down jobs... privilege, and opportunity.

Most of the time, I was told that I was that way because I was simply careless, lacked attention to detail, and that was just who I was.

Deep down, I disagreed, but I did not have any other data points that would show that all of those terms were incorrect.

My first inkling that something might be wrong was when I found myself utterly insomniac and unable to sleep for months at a a time. That was about a decade ago. The feeling I most remember was, "It feels like I have a million ants under the skin of my body!" But no one believed me. That was probably the precursor to a lifelong struggle with thyroid diseases, that was to come.

Then, I realized that I probably haven't ever had a good night's sleep. Every photograph of me as a baby has my mouth open, as if gasping for breath. I took it to an experienced doctor in the US, who told me I most definitely have had sleep apnea since I was an infant, and that if we were to do a sleep test today he would be surprised if I wasn't in the high moderate or extreme range. He was correct.

Eventually, I got both issues looked at, and mostly sorted. (These things don't fully go away, but can be managed.)

Putting aside the issues of not being heard or believed as a young woman in medical system (something that all minorities face, all over the world), I'm pretty pissed. How was I allowed to live through most of my life in such suboptimal conditions?

Why is it that people were happy to just say 'oh, that person has the attention span of a gnat', but nobody asked why?

It seriously impeded my way of life. It got in the way of living, doing, existing. I could not remember anything. I could not wake up for important tests, meetings, interviews. I could not even reliably put a piece of paper in a folder, keep it there, and remember that I had ever done it.

These days, they call it 'executive dysfunction'. But that's a nice term for 'it's your fault until you find a name for it and figure out how to fix it, and get mad that it could have been a reasonably easy fix'.

Oh, I also have ADHD. But I'm not sure which came first. Am I unable to focus on things because I didn't sleep properly for years, had a severely wonky thyroid gland, or is it a bit of everything? I may never know.

What I'm finding out is that it's wild, what I can do with an attention span!

I can file my taxes well ahead of the deadline, and receive my refund before anyone else!

I can pay rent well ahead of time!

I can figure out what I want to do and actually do it!

I'm relearning CSS and JavaScript right now, because I feel like I did not have enough of an attention span or focus back when I first learned it. It's also useful because so much has changed since—like CSS is actually fun now!—that I don't mind.

I'm learning that I am able to sustain a creative pursuit on the side. I have spent a gargantuan amount of effort consolidating my hard drives from Singapore and Malaysia and the US and everywhere in between that, for the first time I believe I have all the writing, photography, video files, that I ever created, in one place. And actually be able to find them. This was not something I was remotely capable of doing at any point in the past. If something was not immediately before me, it did not exist. I have written entire books that I have forgotten I have ever written!

I can even shoot, develop and scan film on a regular basis, something I was never able to do! (I could not even remember what film I used, or where anything was, until now.)

I think most of the people in my early life were happy to buy into the myth that I was a bumbling, forgetful creative person, or to ascribe some kind of pathological shortcoming or disability to me, but the truth was simply that I was a person who needed help, and didn't know that I did.

As it turns out, being autistic and being not at all in tune with your body or with what's normal or expected, not knowing how to ask for help, has health and other vital implications! If I could do it all over again, I would have learned to pay more attention to my body, and learned to apply my autistic superpowers to all facts of life: by digging deep into why something was, rather than simply accepting that "that's just the way I am".

January 31, 2023

Maybe some day, I'll think of the years between 2009 and 2019 as a lost decade. It was a decade of development, when I came of age, when I left home, when I made my home in so many different places in the world, where I tried on different ways of being, as if they were seasonal coats, or swimwear.

Things are different now.

When I was least expecting it, king tides subsided and became gentle lakes. The weather is rarely frosty or humid, it's mostly even-tempered, and cool. I have time to sleep, exercise, meditate, and eat well: I am no longer scurrying from here to there. I know how lucky I am.

I got to recover from a chronic illness that not only took away my physical abilities for a long while, I also got to bounce back mentally from it. From insomniac mania, I now have a well-rested, even-keeled, decently-paced life (and personality). When I think back to those years, to 2012 and right after especially, I wonder how anyone ever kept up with me. I barely did. (Autoimmune diseases are a bitch. Don't let anyone tell you otherwise.)

I have work that is engaging, challenging, and evenly paced. I have the weekends to discover and explore. Surprising to everyone, especially to myself, my new hobbies are fun, slow and old: birding. Cycling slowly. Walking slowly. Hiking. Being in nature. If I'm optimizing for anything (throwback to my startup days!), that's it.

So many weekends spent around the Bay Area wandering about with friends and people I love. Sometimes I look at birds. Sometimes I look at fungi. Many times, I am just happy and so damned pleased to be out and about, and alive.

In line with the theme of 'finding joy in things I have always loved', like playing my piano, saxophone, clarinet for fun, I started picking up my camera again. Over there, on my microblog, I'm documenting all the ways in which my brain gets to have fun. I've forgotten how nice it is to just make things, tell stories, and do things for fun.

I'm done with the hustle.

The hustle that I want to spend time and energy on is the one that's about nourishing my soul. I'm working on some long term writing and photography projects. While it's tempting to think of 2009 - 2019 as the lost years in which I did not do very much creatively, I think it's given me the experiences and time to really become the kind of artist that I want to be. In recovering from chronic illness and hustle-related illnesses, my mind is now clearer than before: I have the headspace now to work and make things the way I want.

It's still too early to share what I'm working on, but know that things I do in this space will always have something to do with one or all of the following: immigrants, California, India, Southeast Asia, food, culture, festivals, climate, nature, mushrooms, birds, queerness, bicycles, music, and maybe more. Those are all of the keywords to my life, these are all of the things that keep me going. Until then, snippets of my creative brain can be found at the microblog, and sometimes also on Mastodon (especially at the #FilmIsNotDead hashtag that I sometimes use).

So instead of focusing on status, success, money, or hustle and grind culture, I'm going to explore all the ways in which I can immerse myself deeply in all of the things that I love, some or all of them at once. And I feel incredibly lucky to have the opportunity to do this.

November 5, 2022

Almost exactly 16 years ago I signed up for Twitter, curious about what it might be. The social web was so young then. I was still in university. The hashtag had barely been invented. Technology seemed like it might change the world, and I was excited to be a part of it.

16 years later, I am midway through my career in technology and I am starting to feel like.. a lot of this was a mistake. Walled gardens were a mistake. Trusting people who wanted to move fast and break things were a mistake.

I can no longer abide narcissistic people who treat people cruelly for fun and profit. I was in Myanmar a lot in the heady days of 2013/2014 where the corporations were so excited about the Next Billion Users coming online in Southeast Asia, but they didn't care if they also inadvertently accelerated genocide. I didn't get a front row seat to that mess, but I knew many civil society activists who were working so hard to try to get Facebook to care.

I cut my use of Facebook and Meta-owned products as a result.

This week, the rocket man unceremoniously let go of many people, many of them people I know. There are no good layoffs or reorgs, but there are too many people who conflate cruel behavior with necessary behavior. Beyond the amorality of it, I am also concerned about security issues if a service like Twitter is left running but everyone's already left the building. As late as a few days ago I still imagined I would 'go down with the ship' or stick around to find out, but after (1) the unethical firings (2) realizing that the new owner was personally censoring things that painted him in an unceremonious light, I decided that I don't need to live that way and I don't owe him anything.

This is how I am going to reboot my social media use.

I am @skinnylatte@mastodon.social @skinnylatte@hachyderm.io on Mastodon. Mastodon is not for everyone. It needs a lot of improvements in UX and it needs to get better at explaining itself to less technical people. But I like what I see right now: if people were falling off the Twitter thermocline (and it feels like that in my own usage of Twitter, as I follow a lot of security and infra and general nerds who are typically at the forefront of the bleeps and bloops of computer work), I've seen a huge wave on Mastodon in the past week alone.

Where before, Mastodon felt lonely, the pace of adoption and follows and responses has picked up so much that it comes close to what I was experiencing on Twitter as a somewhat advanced user.

(Edit. 2 December 2022: I have deactivated Twitter completely. The antisemitism, transphobia and all-around incel-town nature of that community is not something I want to participate in. I downloaded a copy of my archives and I will be hosting a mirror of it here, quite soon. So not all past posts have been lost. BUt I refuse to have any content that one of the people I dislike the most in the world can use for advertising or other purposes. This post has been lightly edited to reflect this change.)

### Cross-post one way to Twitter only

I use moa.party to cross-post. Posting on one platform lets you automatically post the same thing to the other.

I do this solely for archival, and for my 41K Twitter followers to know that I am somewhere else.

I do not intend to originate posts from Twitter after 31 December 2022, but I may sometimes respond to tweets.

For all intents and purposes, my Twitter account will be there, but in cryogenic sleep.

Mastodon scratches my itch for short form text posts, but that it emphasizes intentionality over virality will probably shift my text output into other areas.

How to discover new things

#

Some people say that Twitter was amazing because it was like going into a crowded bar and being able to find the most random people shouting the most random and amazing things.

I was certainly happy to have come across people who baked bread with ancient yeast, the world's foremost lichen experts, people who knew more about pop culture than I can ever hope to in ten lifetimes, and many people who live and learn so differently from me.

My experience with Mastodon has been that once I crossed the 100 follower mark, and I did this by following many people early on and boosting toots, Mastodon became a good enough Twitter replacement for me.

That's the whole point! If you think about it, a tweet is also silly.

So is a google. I am personally rather fond of toots.

If you're as old as I am, practically deceased like the kids will say at the age of 37, you'll have lived through several iterations of webby things.

I was able to keep all my blog content because I always had text files and never invested too much in a hosted platform. Everything run by someone else feels.. ephemeral. If it means something to you, make a copy. Preferably in plain text format. There will be ways to export content, there usually are, but you must have a copy first. If photos are your thing, don't just rely on Instagram to keep the compressed files. Keep your photos somewhere you can access. Make copies.

Yes, I agree. Read fedi.tips. Ask questions. But don't just complain: I think we all need some time of active learning to un-learn the bad habits that big tech companies foisted upon us.

Will it ever gain mass traction? Maybe not. But maybe, just maybe, we don't need that.

Intentional participation over consumption

#

I think I am done with being a consumer, the way I am done with being a product.

I pay for things where I can, I prefer it that way. I no longer use Google, I use DuckDuckGo. I prefer to have Fastmail or Protonmail over Gmail's many conveniences. I'd rather run my own Photoprism server than trust my photos to Google Photos anymore. I gave away all my Echos and Google Nests.

Surveillance technology is not for me, and algorithmic bias and fairness is something that I personally care a lot about, so don't want to be a willing participant of.

I will probably buy non-smart versions of things for as long as I can. I don't want to upgrade firmware on my car or microwave or bicycle.

I'm still excited about technology, but I am not excited about existing business models for it. So in many ways, Twitter's downfall feels like a fascinating, but messy time, to try to participate in social media with full intentionality.

I am done, I think, with the performative cruelty of early social media. No more dunks, no more subtweets, no more yelling. If I am angry about something, and there are many things to be angry about, I plan to log off and count to five and go for a walk and write about it later if I am still angry about it.

I am also noticing that in the three days since I've de-prioritized Twitter as a service, I feel... better. I feel less angry. I look forward to seeing what my friends have tooted at me.

I miss the random coming-across-of-something-great. I have not yet experienced that on Mastodon yet, but it's still early. But I suspect it's similar to what I am now starting to feel about music:

I don't need to listen to the latest and greatest music from artists and genres I don't particularly care for. It's great that Taylor Swift has a new album, but her music isn't for me. If I hear it in a bar one day, maybe I will enjoy it, but I don't need to stream it in lossless formats in many platforms I don't own.

I did recently inherit a used Rega Planar 2 from a very old man, though, and he gave me a bunch of his jazz records that he loved. He bought thousands of records from a jazz store that was closing down, he felt like it he was giving it a home. Now that he was getting old, he wanted me to give them a home too.

So while I still stream music when I go running, or when I am commuting, the music enjoyment I look forward to the most is when I sit down at my record player with the first good speakers I managed to afford, and play Bill Evans' Waltz for Debby. The record sleeve says, this record was recorded at the Village Vanguard, and shortly after, one of the musicians died in a car accident.

Some days, I log in to a private livestream run by some jazz musicians I learn jazz from (I am learning jazz piano and sax), and listen to them play their favorite jazz albums and talk about playing that music and how it's inspired them.

I realise that it is possible to choose to not consume, but to relish and savor.

Much like I have never been to an all you can eat buffet I enjoyed, I won't miss a whole lot of this unnecessary... cruft. But in opting for slow socials, I feel more empowered to share short posts sometimes, longer posts more infrequently, with fewer dopamine hooks to make me feel shitty about the world.

It's also in line with my overall life plan to make more music, eat more delicious food, meet more amazing people online and off, and just really focus on how when everything feels horrible, the most radical thing I can do for myself is to allow myself to enjoy beautiful things in ways which are still meaningful to me. If I can do all that while helping advertisers flee a platform that's become a vector for hate, and help lighten the pockets of a man I greatly disdain, that's even better.

In the meantime, I will listen to records and go bleep bloop sometimes, or infrequently, or perhaps never at all.

November 3, 2022

Sometimes I think of countries as restaurants. Every country has a different concept. Every country has something to offer. Some have menus, some do not. Some are large multi-concept food halls, others are exclusive white tablecloth places where people have to fight for the scraps—outside.

My country, Singapore, is a prix fixe restaurant where there is a daily special. One soup, one main. You can take it or leave it. If you have more money, you can upgrade some parts. But it's still a fixed menu. You can't change it very much. You can't go anywhere. You can only stand up and sit down. The waiters are quick to shoo you out, or push you back down, whenever you feel like you might want to do something different.

I now live in the US, which feels like a multi-concept sort of place. On level 1, there's food hall like one of those in a mall with funny names. All kinds of things, but nothing that will keep you satiated for long. Just fast food and snacks. Make your way to the top, and you'll find a stuffy dining room. Realistically, most people will spend all of their time between levels 2 and 99. You can take the elevator, climb the stairs, do whatever you want. There are lots of ways to go anywhere and you can go at any time. You can do whatever you want. Some people throw poop into their food, and eat it, and that's fine too.

In the prix fixe restaurant, you eat the same thing everyday and maybe you get bored. You never get food poisoning. Everything is safe. In the food hall for insomniac people, you can eat lying down, shoes off, with your feet if you like. There are no rules, there are no bouncers. But you get food poisoning every other day. Unless you're on the top floor with all of the silver spooners. There, you get proper chicken, not the hormone-filled ones that taste awful. You get real vegetables. Life up there is pretty sweet, nicer than the top floor of any other restaurant in the world.

It's June 2022, and I am in Singapore. I am lying under my blanket feeling angry about the state of America. There are more mass shootings than I can count this week. I can't imagine what parents feel about losing their children to gun violence. I think about how when I walk by the thousands of homeless people in the city I live in, I see glimpses of their past lives. The backpacks they must have carried to work, and how they now store everything they own. The fancy camping tents they probably slept in when camping for leisure, that are now the only shelters over their heads. Why do I keep going back to somewhere where I get food poisoning all the time?

I don't have the answers. I think, though, that after a lifetime of being safe and repressed, it was interesting and novel to live somewhere that was the opposite. The country that always give us food poisoning also has delicious food and incredible experiences on every level between 1 and 99, whereas most other countries only have a few. A few ways of being. A few ways to exist. But the diarrhea is bad and sometimes there are no rest rooms.

That for people like me, who could never fit in the box of that my country demanded of me, I don't know where else I can go. That every time I board the plane between both cities, I am making the choice between physical and psychological safety, rarely both.

You learn to duck under the people flinging poop around. But at home, you can only sit down or shut up. Some people say surely there must be an in-between country that isn't either / or. Maybe. But what I'm afraid of is that many of the in-between countries hide their poop so well, and things look great, until you get there and then you have to sit down or shut up again because you're not from there. Because you should be grateful you no longer live in the other places.

I'm now of the opinion that there are no good countries, the best you can do is try to make a decent life for yourself anywhere. If you have the opportunity to pick, like I do, that's already a huge privilege. If you're queer, multi-national, like us, the number of possible places to live is tiny. You've got to make the most of the ones that work. But as the world turns hard towards authoritarianism and fascism, I don't feel like there are any good places to hide. I don't believe there is a single country worth moving to that is going to be able to avoid that wave. I also don't believe anyone who says, "my country is better than that one": they always come from a position of privilage, and my position as an immigrant to their country is never going to be the same. They also never, ever know what they are talking about, if they're not queer and intersectional in the same way we are.

On this trip home, it was nice to not have to think about food poisoning. I know exactly what my life back home will be, what it will look like, maybe even where I will live and what I will do. It's been tempting to imagine going back to that. But I also know that in a place where I can only sit down and shut up, repress my gayness, hide my photos of my family at work, where I must be gay but not too much, where I can be out but not too loudly, where I can live as a queer person but not have rights, I'm reluctantly crawling back into the place that gives me diarrhea every single day.

My country says: it's hypothetical that you'll ever have food poisoning here, because everything is perfect here, so why are you mad at me, and why do you leave me?

I'm mad that I have to live somewhere that gives me food poisoning. But at least there, my wife and I can be together, as my wife, even if we have to poop more than usual.

February 21, 2022

It feels like not very many years ago that hackathons, free beer and drunken nights out with startups were, for a brief moment in time, cool.

Perhaps it was even normal.

It was in this environment that I came of age, so to speak, in my work. It was therefore no surprise to anybody that I soon developed a drinking problem. Like many in my industry.

I pursued the drinking with the fervor of a person who also threw themselves into the work. Work hard, play hard. All of that. I learned the ins and outs of whisky the way I learned to manage products. I collected the certifications and classes for my outsized interest in alcohol the way I also worked on my tech skills. Many of my friends left the tech industry to distribute or sell alcohol. When I went home briefly to Singapore, people sent me so much alcohol that it lined the walls of the tiny hotel room I was in.

I did not drink much of it.

By then, I was starting to examine why I drank.

I drank, because it was routine.

I drank, because it was expected of me, for a time. To get along with the boys in tech, I should drink as many IPAs as they do.

As I got older, my body could not metabolize the alcohol. Hangovers felt worse. I felt sluggish. Even though the peats of whisky and the hops of craft beer are still things that I love, the drinking lifestyle is completely over for me.

After I moved to San Francisco, I found that the party was over. The San Francisco of free beers at work and boozy networking events that I saw and loved when I first visited in 2012 was not the San Francisco of tamer stuff, the one that I know and love today. Maybe the party moved to Miami. Maybe we all got older and collectively decided to do something else with our lives. Maybe returning as an adult in my 30s with a wife and family made me see that there was more to life than black-out stupor every weekend.

I was also tired of being sick.

A decade plus of round the clock hustle. Startup myths floating through every part of my brain and my soul. Fueled by a lot of craft beer and gin and Scotch. Coffee the rest of the day. At some point, that party had to stop.

I was very sick for a very long time. Not specifically because of alcohol, but it can’t have helped. Autoimmune disease hit me like a truck. I had all of the things: I was a woman, I was getting older, I didn’t sleep much (because hustle culture says to sleep only when you’re dead), every city in the world from Singapore to San Francisco to Seoul was starting to meld together. Every city felt the same. My life was the same. Work. Alcohol. Raise funds. Build things. Do it all over again, thinking you’re a baller, but something had to give.

I was tired of being sick.

It took me almost eight years to get my body back to where I was, before hustle culture and autoimmune disease killed it. In March of 2021, I put my running shoes back on and went for a run. Running had been such a big part of my younger life. It was different then: it was a different hustle. It was also a competition. It was about winning.

I didn’t feel like a winner in 2021. Almost nine years after the day I was sent to the emergency room with my heart rate through the roof, my body mass dropping at an astonishing speed (I was 5 kilos lighter in the evening compared to what I weighed before dinner), I resumed running again. I was slow. But I was happy. I was happy to be able to run at all.

The autoimmune disease wrecked my body for years until I could no longer stand or reliably support my body weight. I would be walking in the streets and then I would fall and not be able to get up. I was not able to feel my legs. Everywhere, from Singapore to Jakarta to Seattle. At first it came in short bursts: a minute at a time. I got up, I resumed my life. Then it came and it stayed for half an hour. Then an hour. It was like I was black out drunk, but I was not. I was fully conscious, but I could not move from the waist up.

Lucky for me, there was a way out of it. It required me to fully change my life. I voluntarily swallowed a pill that had been made at a nuclear plant, blasted my thyroid gland with the full force of radiation, and watched my body and my mind struggle through mania to sluggish slowness. From hyperactivity at 4 in the morning to being unable to move from bed. I watched my weight yo-yo between extremes, as my now-defunct thyroid gland struggled to establish itself in my new body, one without the ability to make its own hormones.

It would be 2 and a half years from that moment when I was able to run with any regularity.

And when I did, I didn’t want anything to hold me back. There was nothing to win. There was just the running, the freedom of being on my feet again. There was the Golden Gate Bridge that I ran towards daily as a symbol of the life that I have found for myself here. There was the weekend bikecamping trips I’d go on with friends: stubbornly and barely pedaling uphill at first, through the hills of Marin county’s many hills, eventually finding my pace. There was the 4-day Yosemite backpacking trip I went on in September 2021, where I surprised myself by climbing nearly ten thousand feet two days in a row. Where I hauled myself over the cables of Half Dome and thought to myself, life is pretty great, I never want to do anything that will stop me from living my best life again.

Gradually the dopamine hits from the alcohol turned to the daily dopamine hits from the exercise. From hitting my goals. From walking twenty thousand steps a day. From going on long walks with my little dog. From running ten miles a week. Then fifteen. Then twenty. Then more. Suddenly, I didn’t want the booze anymore. (Around the same time, I also started talking to people about ADHD. I started recognizing that the impulse I had to drink was indistinguishable from my ADHD need for constant refills of excitement. I worked with an ADHD peer group on goal-setting behavioral change that I wanted to practice so as to improve my life. I started with, ‘well maybe I won’t drink any alcohol other than wine’. But soon I found that I didn’t even want that at all.)

There’s still bits of that lifestyle I miss. It feels shockingly difficult to find a place to meet people and sit down in the evenings without substantial amounts of alcohol. But that’s changing. As I began to document my non-alcoholic journey, I found that I could still go to the places that I enjoyed, I simply had to ask for the non-alcoholic version. I explored the world of non-alcoholic craft beer, and de-alcoholized wine. I turn to those, at times, for what they call in India, ‘time pass’. It’s habit to nurse a drink and do something somewhere; but I do substantially less of it too. They are simply anchors into a past life that help me feel like I haven’t gone ultra cold turkey, because the feeling that I can’t do something also makes me want to do it. After six months though, I simply don’t want to do it at all. But I’m glad the non-alcoholic options exist. Because I truly despise soda.

The last couple of years have been a period of long introspection and learning for me. From learning to work with my neuro-diversity, to picking up new skills (I am currently learning the saxophone!) and more, my life has truly turned around since I gave up the hustle and settled down. It’s hard to overstate the importance of how my supportive and stable marriage helps me grow as a person. In Sabrena, I have a life partner who doesn’t shy away from the hard questions: why do you drink? Instead of saying ‘stop drinking’, she had me question the impulse behind my need. I sought the tools out myself, but I was able to share my progress and growth as a person and in every endeavor, no matter how small, with her. She is my biggest cheerleader.

Just like that, I’m six months sober. I’m running twenty miles a week, going on thirty. I’m planning to backpack and bikecamp. I walk endlessly with my little dog, who also seems to have found a new lease on life here in San Francisco where she is far more active and alert compared to humid, balmy Singapore or KL. We walk for hours. We climb hills. We look at the many, varied views.

I’m present for all of it.

November 30, 2021

Some time ago I read a tweet by a queer Singaporean asking why any queer Singaporean would move to San Francisco, citing the following shortcomings (not verbatim):

- San Francisco used to be a place where queer Singaporeans would move to, for safety reasons, but perhaps those safety reasons aren't that dire anymore

- San Francisco / the US is the heart of the hegemonic world order / imperialist system

- We probably like the white gaze

- San Francisco provides the opportunity to be a Joy Luck Club Asian queer

There was a time in my life where those thoughts resonated with me.

This topic has been on my mind since I moved here and, surprisingly, did not hate it as much as I imagined I would (I did not like San Francisco at all when I came as a tourist).

Unlike many other immigrants I've met here, who have left deteriorating and debilitating circumstances, my 'why I moved and how has it been' calculus is different. I did not move for material comfort. I am, daily, reminded of how I left home, away from material comfort, and my support systems, to be here. (Not to mention the tremendous amounts of social privilege I've left behind.)

Some time in 2012, I was pretty satisfied with my life as a queer Singaporean living in Singapore. I was in a high growth industry (tech), I got to date (a lot), I had many opportunities to create and carve out a life for myself as an upper middle class Chinese Singaporean gay woman who'd probably end up in a relationship with someone like me. In fact, when I went home recently we hung out with my ex (as queer women do), I took a photo of their home office in their absurdly beautiful Bukit Timah home and I captioned it in my phone as: "the life I would have had if I stayed home".

Every conversation when I was home revolved around, "when are you coming home?" because it seems unexpected, even among some types of minorities in Singapore, to entertain the idea of leaving the supposedly best place in the world (that we still all complain about anyway).

I found that my connection with Singapore was weakening. Other than family, I don't have anything to do there, or many people to spend time with. I have loads of acquaintances, of course, but many of my friends are.. elsewhere. (Not all of them to the hegemonic core, many of them to many parts of the world, including China, Vietnam, Indonesia.)

Still, every conversation (especially with my family) was around: so are you done yet with San Francisco? Isn't it absolutely terrible, that country? When are you coming back to this superior place? was the underlying question. If you're an always online Singapore leftist, your concerns with my city of choice probably has more to do with the above list of questions. If you're not a leftist, your concerns with my city of choice probably has to do with things like safety, medical bankruptcy, housing, why someone would realistically choose a higher cost of living and physical discomfort (as mentioned, Singapore is far more comfortable, materially, in nearly very way), and give up substantial amounts of socio-economic privilege.

Why people choose to leave home is deeply personal. Every situation is different. I moved here exactly three years ago with my wife and my dog when we suddenly had to make a huge life decision on the spot, when her work visa ran out and we decided to get married. We were lucky to have the option to come here, and to be able to thrive.

I learned quite quickly that I would have survived in Singapore (it's getting harder for queer people there), but I no longer felt like I could thrive. In spite of my immense privilege.

I felt like like the short-lived optimism I had for Singapore expanding queer rights was over. Even if 377A is repealed, I don't feel optimistic. I don't feel like I want to wait for incremental improvements. That's not to say that I don't want to do the work. I did, for a time. And if my circumstances were different, if I had decided to spend my life with another Singaporean person, if I was okay with surviving and not thriving, if I was able to shut up and be okay with the already tiny space around me in Singapore, eroding further and further; perhaps that would have been different.

I don't pretend this city, or this country, is perfect. Far from it. Unlike the home I grew up in though, it lets me say so: even if I am not a citizen. No country is perfect, so for now, we'll enjoy the wide open space of California, where, frankly, life is pretty good (if you can hack it). I feel immensely lucky to be able to grow as a person out here, far from home, while also having the ability to move back to my country, which has given me so much, yet currently exasperates me, whenever I need. I'm certainly cognizant of how this is a huge thing to have. So many of the other people who have moved to where I now am, no longer have a country at all. After three years in San Francisco, I feel like I've finally passed the moment of transience and 'uprootedness' that I've felt for so many years, and that maybe 'home' is always 'small cities surrounded by the sea, that punch above their weight'.

But there isn't a single day where I don't grieve what I left behind.

November 22, 2020

Before I came to this country I led a very different life.

My luggage was never unpacked. My passport was tethered to my body. My weeks often began with breakfasts in Yangon on Mondays and ended with drinks on Jakarta rooftop bars on Fridays. On weekends, I might retreat into a Balinese forest alone or return home.

Home was one of Asia’s most expensive cities. At least, it was where I paid rent and where I have the largest number of relations of all kinds. Home didn’t feel like home since I was never home for more than three days at a time, from the moment I graduated from college. I could never buy a gym membership anywhere. I simply didn’t know where I would... be.

My life here is quite different.

I have not left my neighborhood much in the past year. The longest trips I have taken have been occasional bicycle trips across the Golden Gate Bridge, where I sometimes like to cycle to my favorite bakery and then put my bike on a bus home (just say no to the hills of Sausalito). So many people are writing stories about how other countries are doing pandemics differently. This is mine, except I stayed on and am in it for the long haul, fully cognizant of all of the ‘benefits’ I am missing out on.

My friends are having brunch and cocktails back home and I know in my bones that would be me, if I was in Singapore right now, too. Because I am bougie like that and I know it.

But I am not at brunch. I am huddled at home, like I have, every night this year. My dog is asleep next to me, farting ceaselessly. I have canceled all holiday plans. We are not going anywhere.

During the work days, I work with a team of thirty something brilliant and kind individuals who, together, are trying to make a difference for the city we love during this difficult time. At nights, I put on an apron and trudge to an empty kitchen near my home to churn, literally, batch after batch of ice cream so that I can bring some joy to people in real time.

It feels like exactly where I need to be.

It wasn’t always an easy feeling, though. In conversations with therapists I have learned that the inability to make plans for the future, any future, is causing everyone all kinds of anxiety. For international folks like us with our lives strewn all over the world, it has been a special kind of logistical challenge. When will we ever see our families again? In all these countries?

Back in March just before shelter-in-place came upon us, we already knew the extent of the damage of this virus from news from Asian cities. We semi-seriously considered waiting out the pandemic in Singapore, where a good healthcare system and mollycoddling levels of government support seemed like a good idea. From rumblings from an assortment of compatriots I gathered that nonstop flights might end from San Francisco; that if we went home now, things will be safe; that you really don’t want to be stuck here in this country with its impossible healthcare system and not have any help figuring out something so unprecedented.

Occasionally, I dial in to Zoom conversations hosted for Singaporeans on the west coast. They always kick off these meetings by sharing latest stats. We marvel at the numbers. We laugh at the charts that are made showing how we have significantly less confidence in the American government’s handling of this pandemic compared to our own. We run through the numbers of how many of us have decided to weather it in Singapore or hunker down here in the Bay Area.

Somehow, those of us with not entirely clean cut Singaporean lives are hunkering down. Our partners cannot return with us. Our children cannot. I continue to be frustrated by the inability to plan for the future in any form. So I churn more ice cream.

If I were in Singapore, I would be at brunch. I would be checking in to all the locations I visit throughout the day with the app that every citizen has access to. I might be walking down a quiet residential street like my parents were when I called them a few days ago, and the biggest concern of my day might be that I paid too much ($5) for a bowl of fishball noodles.

But before I get to brunch, I would have to find my way to Los Angeles, the closest city where I can still get on a plane home. I would only be able to board the Singapore Airlines plane if I had my bright red passport, which I do, but that my wife does not. On entering the plane, probably in business class (as I would have upgraded with the miles I have studiously collected over the years), I would sink into the leather seat and feel relieved when I am given a copy of the Straits Times by a person who can pronounce my last name the way it is supposed to be pronounced (Tanh, not tan as in what the President does to get his famous orange color). I would sleep for the entirety of the sixteen hours, because I sleep like the dead in both economy and business class (and at the back of a boat or upper bunk of a train). I would land and I would hear the familiar sounds of Singlish, Malay and Hokkien at the precise moment the plane doors open onto the aerobridge.

Heat and Hokkien always hits me like a wave. I would scan my passport and then be whisked to a five star hotel where I would be strictly quarantined, before I can be released back into the world. Then, depending on the outcome of my tests, I would either be eating fishball noodles with my parents, or declared an ‘imported’ case by state media.

I will not be at brunch for a long, long time.

Instead, I have not cut my hair since January. My dog is so unused to being more than one foot from me that she now wanders to the bathroom if I am there for more than a minute. I am sequestered in my 300 square foot apartment that somehow has space for two humans, two animals, and all of our life’s possessions. My wife has bolted a fold down desk onto a wall. When either of us needs to use the bathroom, we flatten between the chair and the wall, sometimes without appropriate amounts of clothing (usually me). At various points of this pandemic, especially during the combination election and pandemic anxiety weeks, I plot and plan and figure out logistics. I carry bags of laundry to a laundromat at quiet hours, and wish I did research on how there are rarely any washers or dryers inside American apartments.

That is my way of dealing with anxiety. I figure out logistics. Which is an activity that is, in itself, anxiety-inducing. But never mind. I write to the immigration departments of various Caribbean countries. I research golden visas in Taiwan. I look at Estonia. I do all of this first for the animals, and then for us. All the countries that require any amount of animal quarantine are crossed from the world map that is in my mind. So no UK, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore or Hong Kong. Immigration departments write back and I promise to pay them some time after November 4, 2020. I never do.

I scan the news for information about 45’s latest immigration-busting moves. I realize, for the first time in a while, that we literally have nowhere else to go. I stay up until 7 in the morning to watch a needle tick in one direction or other in an election I cannot vote in. I dabble in more logistics, this time reading in other languages. Reading in my second and third languages will be less anxious, I tell myself, because I won’t understand all of it. It doesn’t work. I freak out again, just in other languages this time.

Seventeen days ago I woke up with needles pointing in not so bad places. I ghost Carribbean immigration officers. My love story with ‘Murica continues. Another tragedy strikes. America crosses 12 million cases; yet more than a million people are expected to fly this week for a holiday that celebrates genocidal activities. 95% of my state is on a 10pm curfew. My city, which has high levels of mask compliance and some levels of official responsibility, might join the rest of the state very soon. Life goes on. All I know is life will not need to be in the Carribbean.

The sun sets at 5pm and I turn on a ten thousand lumen lamp for several hours so I don’t get sad.

From time to time, my wife and I wonder: what will our life be like in Singapore, right now? We think of our beautiful apartment in the forest there. We think of our many brunches. We think of chicken rice. But mostly, we think of how we will not have a life in Singapore at all.

She wouldn’t be allowed in. Right now, because of the pandemic. But also always, because she won’t be allowed to be my wife.

October 7, 2020

In my younger years, meaning when I was a tween, I became acutely aware that my life would be different. I dated boys because I was supposed to, but whenever they said they loved me or that they wanted to marry me, I just shuddered. I don't like it when men sweat, I told them.

In hindsight, that was a big, red sign. I learned, in quick succession: I don't like it when men sweat. I don't like it when men sweat on me. I don't like the way men smell. I don't like men. Period.

When I was eighteen I felt like I was at a crossroads. "Am I bi? Am I gay? Am I... just a slut?" I could not tell. When you are a teenager, everything is possible. All doors are open. You can live anywhere, be anywhere, sleep with anybody.

And so on and on it went.

Eventually, I did find out: I am lesbian. I am a dyke. I will die on the hill of women-smells and women-sweat forever. I think I found that out when a man asked me to go to IKEA to pick out furniture with him. I told him he was really hot but, I would never go to IKEA with him, or with any man, now and always. It felt far more intimate than whatever we had gotten up to. I don't like man-sweat.

Even with that clarity behind me, I still had no clue what the hell I was supposed to do with that information. I lived in Singapore; I had gone abroad. I had flirted with the idea of going somewhere else. Nothing seemed clear. That sort of clarity, about what I would do and how I would do it, would only come later. (Again, that moment struck me like a thunderbolt, out of nowhere. It just did, and I don't know when it did.)

Yet I clung on to the idea of being thirty five as the day I should have 'figured it out'.

Maybe I did?

I have figured it out, in that I have learned that my sexual orientation, which once defined me as a person, continues to be a political position but it is not the entirety of who I am.

I have figured it out, in that I am married to a woman and we have a dog and a cat, just like I imagined when I was a wee tween, but I came to that very differently as well.

Dating in Singapore was strange, but not unlike being queer in any other major city. I was.. comfortable. I went on a few dates a week. At 35, I feel tired even thinking about the amount of energy I put into dating in my 20s. But it felt like the sort of thing to do a couple of times and get over with.

Love came to me in a way I could have never imagined. I was used to meeting women on the apps, meeting women in queer bars, meeting women everywhere I went, everywhere. But I had not yet done the classic queer woman move: I had not yet dated a woman who had dated the friend of a woman I had dated.

Who knew that would have solved all my problems?

From there, we went: Yishun, to Bali, to Bandung, to Kuala Lumpur, to Jakarta and then to San Francisco.

Our love (and life) here is exciting for the most part. It is also mundane in some ways. Gone are the days when I would stay up till 4 in the morning, excitedly watching soccer or drinking tea or poisoning my body and my brain in some other way. Instead, I run, skip, walk for miles in the beautiful city with my dog, and sleep ten hours a day. It helps.

It also helps, I think, that I finally have a job where my interests (doing good things that help people) with my skills (product management and mucking around with software generally) intersect. It truly makes a difference.

Even if I could not have foreseen that we would live in this country at its most vulnerable, in that it has a narcissistic Anti-Christ-like grifter at its helm, our life in its most expensive coastal city is generally... nice.

I stay up some nights trying to figure out what the hell is going on. Maybe it's nice to note that at 35, the things that will confuse me are external, instead of inside my head. Anything can happen in the next couple of days, weeks, months. There are some challenges relating to being a queer transnational couple and work visas and pets and things like that, but I'm still glad we have what we have.

Being able to live for the last two years, as we have, as a queer family with legal recognition (and insurance!), has been more than I imagined. At eighteen, or at any other time. The world goes on. I am a year older.

But this year, I am way better off than any version of 35 I imagined for myself.

September 9, 2020

Today's headlines:

Today's soundtrack:

I don't have any commentary other than 'oh shit'. So I grabbed my camera and walked around a bit. Everything is weird and I am going to drink tea and stay calm.

I think I'll truly freak out when work stops along Van Ness. Until then, as long as Van Ness goes on, so will I.

August 19, 2020

Every overseas Singaporean has the same fear: that when we return, we will not know our way home.

Our city builds and tears down much quicker than most other places. Nothing is safe. The price of progress: everyone's memories. No time for nostalgia, or poetry, when we can have... growth.

When I move between worlds, my words and ideas shift.

Apartments. Flats.

Elevators. Lifts.

Use public transit. Take bus and MRT lor.

Nothing ever stays the same.

Jalan Besar, Singapore. 2019. Public housing and transit.

When we return, there are more towers of glass and steel. Like our displaced accents when abroad, moving between Singlish and that of wherever-the-hell-we-live, our country's buildings now look like they want to be a little bit of everything.

I hate those buildings. I hate that waterfall in the airport, I hate the infinity pool on the top of the world, I hate the overwrought fake plastic trees and every single thing in a tourism board glamor shot. Glamour shot.

Instead, I take long walks along the old civic district. There, old buildings, colonial and brutalist, form my happy path. In a way, I love this part of town because it changes, but it stays the same. Hours of riding on the top level of the meandering bus to the ends of the island and back, sometimes ending in a boat ride to an island or more frequently, noodles.

3 A.M. staggers between hostel and Mustafa, my tummy filled with warm naan, kadai chicken and Punjabi uncles giving me lesbian dating advice (Their advice was usually some variation of "always pick the Indian girl").

Wandering every story (floor) of Sim Lim Tower, looking at batteries, wires, cables. My grandfather worked at a dry goods market that is now a nearby field, probably slated for a new apartment (condo) or hotel.

Memories are a leaky, unprofitable thing.

Jalan Besar, Singapore. 2019. Wholesale electronics and late night food.

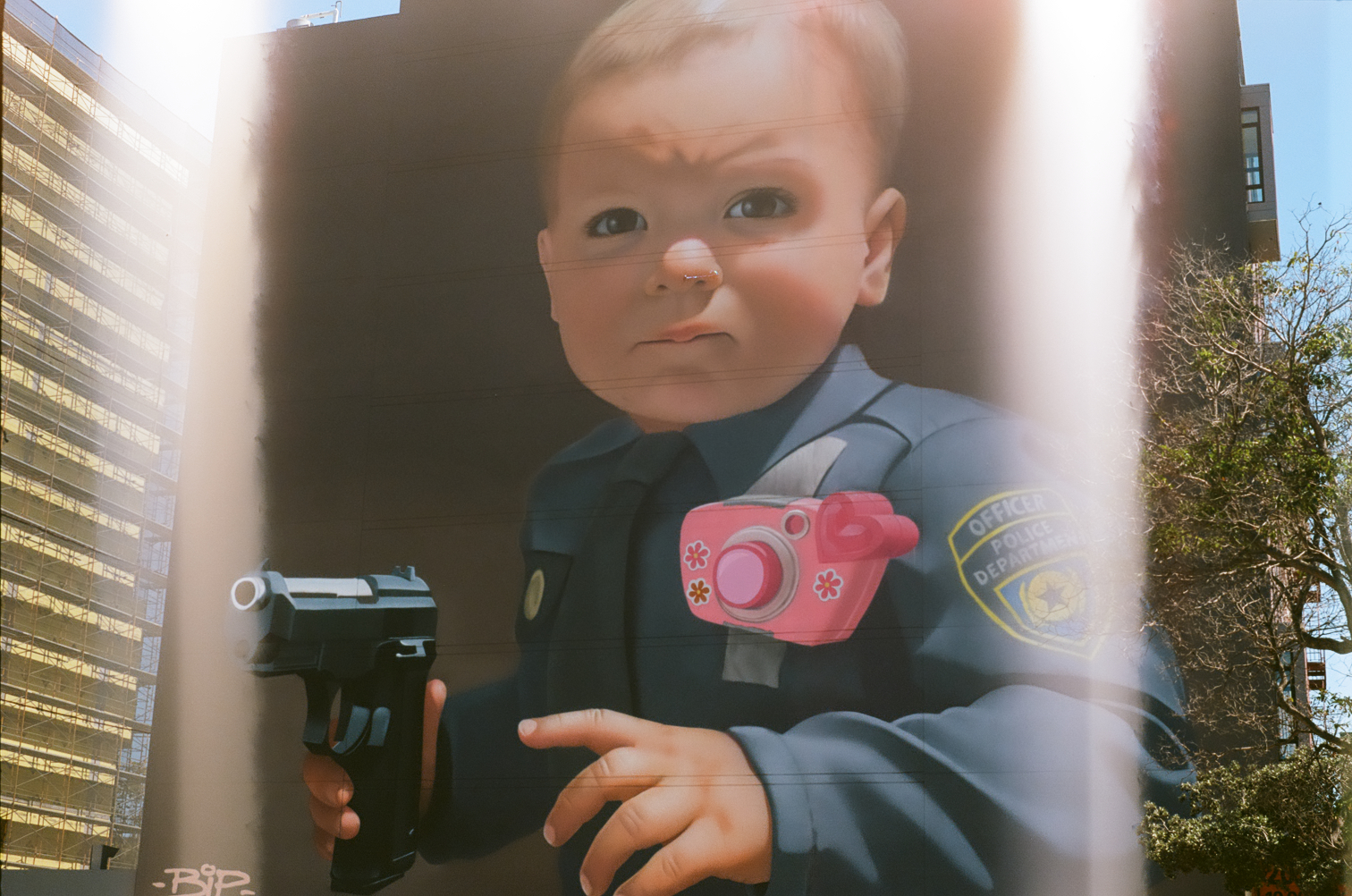

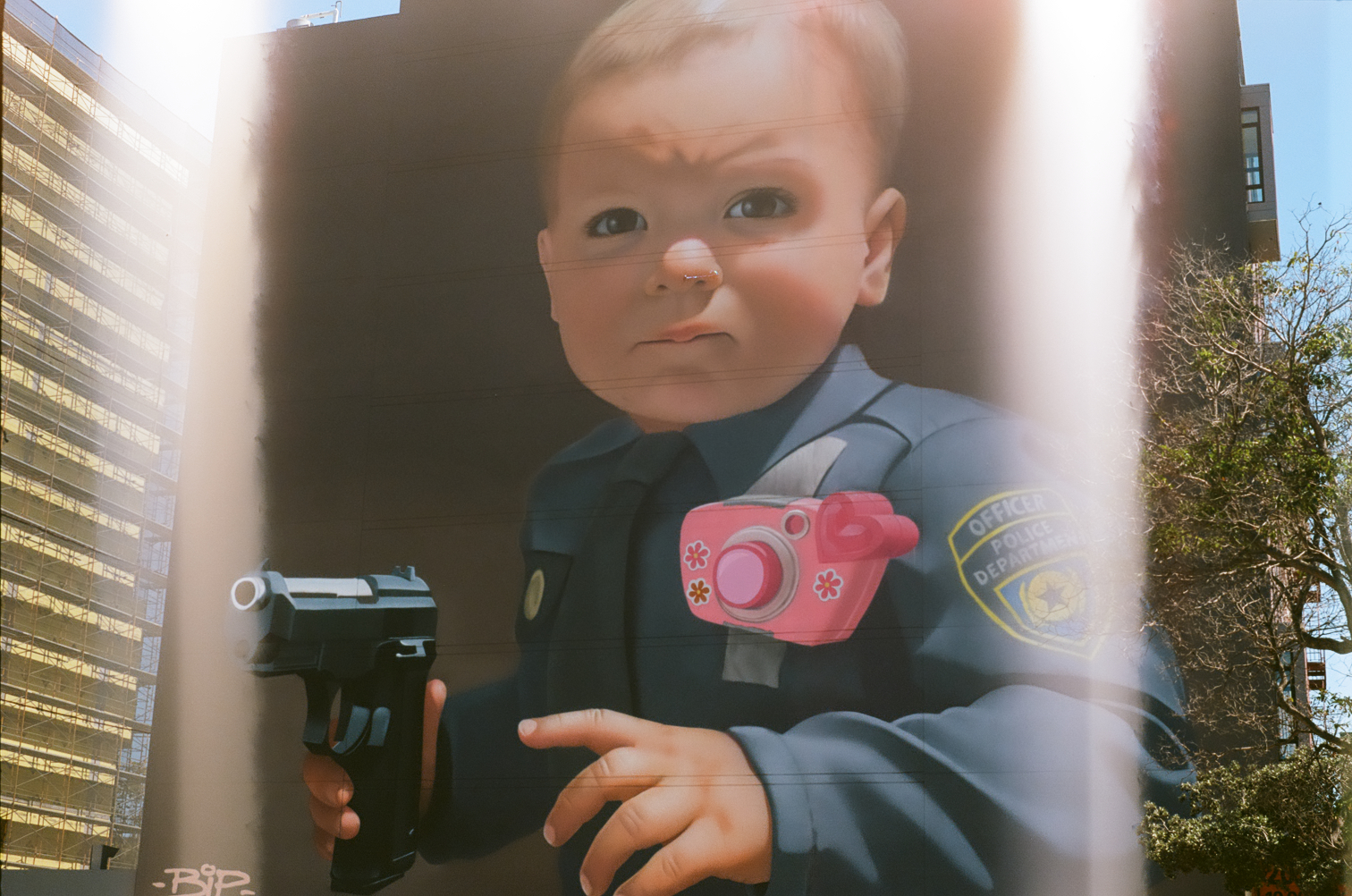

But I live here now. Somewhere with giant babies holding weapons.

How did I go from a small city to an even smaller one? I'm living car-less in a pandemic (I don't drive, because, I've always had transit), in a seven by seven mile city. So many things are happening in the world, but this country feels... like a lot.

It is a lot. It's a whole lot.

For now, we're strapped in and waiting with bated breath to see what's in store for the next couple of months. As I write this, there's a man furiously banging on cars and cars driving badly and there's another man yelling stupid bitch at the top of his voice at an imaginary person, but they don't scare me as much as the politicians.

We take long walks in every direction.

To to west, we walk by recently gentrified Hayes Valley, with murals and giant babies.

To the east, we sometimes stock up on Asian snacks and all the Indomie we need from Pang Kee in Chinatown. To the north, a range of outdoorsy options. Chrissy Fields, where you'll eventually see the Golden Gate Bridge; the municipal pier, where I've been known to sprint up and down when I feel like I need to run very fast for no reason at all.

Hayes Valley, San Francisco. 2020. Giant baby mural.

Hayes Valley, San Francisco. 2020. Dog and wife waiting for me to be done taking photos with a manual camera.

Unlike where I'm from, this home of mine barely changes. We recently watched footage of Charles Manson's San Francisco days and... so much of the city is the same. The gurus have left Golden Gate Park, and they've moved online to become productivity deities who preach the gospel of four hour work weeks and cryptocurrency.

It's going to be okay.

Hayes Valley, San Francisco. 2020. Wife in yellow dress waiting for me to be done tweaking my camera settings.

May the next roll of the film not leak light. And this country not go completely to the dogs.

August 16, 2020

On Twitter, where I live, I posted snippets of the things I have done, the places I have been, the places I have gone. Where they might have felt jumbled up and messy on a blog or Facebook post, the Twitter thread / tweetstorm format seemed to be a natural home for my adventures. I am grateful for the mess that my early adulthood sometimes felt like.

Growing up in Singapore, my future felt as small as the country of my birth.

A mere 31 by 17 miles, it was the island that was also a city that was also a state that was also, somehow, a country.

When you bought anything online you'd get tired of typing or picking: city, Singapore. State, Singapore. Country, Singapore. Credit card issuance country, Singapore.

Singapore, Singapore, Singapore. Singapore.

Yet when I was in school, it was not the lay of the land that felt suffocating. It was the geography of the mind, the mountains we did not have, never even got the chance to climb, that I could not stand.

The moment I could, I ran away.

At first, it was for a few hours at a time. Age 13, I would grab my passport from my mother's chest of drawers where she kept all of our passports, passport photos, and other important things like that, guessing (correctly) that she would not notice.

School ended at 1.40 P.M. Everyday felt as warm as the next. If you grew up in the tropics you don't describe the weather as 'sweltering' or 'oppressive'. It simply is. In my school uniform, with sweat patches under my armpits, I would board SBS Bus 170 bound for Larkin Terminal, Johor.

It was a trip I had made many times. My grandmother was born there, Johor Bahru was the Teochew homeland outside of Swatow. Johor. It wasn't Bangkok or Phnom Penh, the capital cities with large numbers of Chinese people from the same patch of southern China like I supposedly was from. Johor was more like Pontianak. Sleepy on the surface, but a different world on its own if you knew its secret language.

I did, and I liked that.

In those days, it was not surprising to see children dressed in the school uniforms of another country wandering the streets of Johor Bahru. The city was joined at the hip with mine, except it was tethered to another. Pass all of the rubber plantations, seeing the landscape become more oppressively green and witnessing the heat become even more so, and you'd end up in Kuala Lumpur, three and a half hours later (two if you drive really quickly, like my ex used to).

14 years later.

I made the journey in the reverse. It was the morning I was to pack everything I owned, and a dog, which I now owned, alone, into the Proton Kelisa.

Five years before, that car would speed southwards to say hello, a few times a month.

That day, it sped faster than it ever had, eager to dislodge its contents after a few difficult months. There's never an easy end to a story, even when you try hard to make it so. I moved north with two bags, a vacuum cleaner and an ice cream maker. I moved home with two bags and one dog.

In less than three hours between Bangsar and Tuas, I was ready to present Cookie to animal control. We had to join a line full of chickens, which is maybe my only memory of that hazy, no good day.

What would her life be like in the country of my birth, I wondered. I hoped she would like it. In 2012, I thought I was going home for good.

I have had a life of adventure. I have lived in more cities than most people have visited; I have gone to many, many more.

How did I do it, people often want to know, expecting some kind of secret like "I was an influencer and people paid for my trips".

There isn't one. It didn't feel glamorous, not when I lived in $5 rooms and avoided rats on 30 hour train journeys.

I used to think the secret was that I jumped headlong into anything fun or exciting that I saw, with barely a consideration for the cost or trade-offs.

I now know that I was handed a huge amount of privilege, and that's the secret. I worked two to three jobs all through college, at the same time, so that I could make the hard cash to go on these adventures. That wouldn't work if I wasn't also making Singapore dollars.

I had the luxury of taking off for months at a time, not having to be the caregiver for anyone at home, because everyone was healthy and financially okay, and I could live off the SGD to THB or MYR or INR exchange rate for quite a while.

Eventually I rearranged my life to lead this sort of life. Even before graduating from college, I made GBP and USD and EUR as a freelance writer and photographer, on top of the other two jobs I had in Singapore when I wasn't traveling. And when I was done with the freelance industry, because print media was dying, there was no shortage of even-better-than-SGD-paying tech jobs for me with the skills that I had.

My life has been a series of opportunity after opportunity, of good luck following another, upon layers and layers of privilege.

I turn thirty five this year. When you get to your thirties, you no longer say "in three months", or things like that. You're officially thirty-something.

My wife thinks that I am the luckiest person she's ever met, even after accounting for privilege. Maybe.