Wobe’s founder on the basics for technical success

“Jakarta Panorama” by Gunawan Kartapranata [CC BY-SA 3.0]

“Jakarta Panorama” by Gunawan Kartapranata [CC BY-SA 3.0]

If you’re a founder too, technical or not, you’ll know all about the struggle.

The struggle: late nights, being poor, having everything go well and then not, the very same minute.

For me as a non-technical founder, and I’m sure for many others, the struggle is also: how do you build things? and other assorted questions.

If you build it, will they come? (Customers)

How will you build it? (Teams, product, culture)

What, indeed, do you build?

I’m always perplexed by founders who want to only move fast and break things without knowing themselves what they’re moving or breaking. If you ran a furniture company, had aspirations for it to be the best in the world, wouldn’t you want to at least know how to wield a hammer?

This post documents the who, what, why, how of our year-long journey building technology in the emergi-est of emerging markets: Indonesia.

Wobe works to improve access to payments and utilities at the last mile: our unique application and its surrounding ecosystems of microservices and tools let us offer regular people the opportunity of running their own business. They can sell recharge (of phone airtime, data, electricity, water and other vouchers); their communities benefit from cheaper and more efficient ways of topping up, without having to travel. We work with grassroots organisations to bring about greater benefits for low income women who come into our networks.

Who we build for

More than how you build or what you build, is the question: who do you build. This is tied to the mission of the company, and resonates through the company. It also has to do with what the founding team, not just founders, cares deeply about.

I had the amazing opportunity to spend a year in Myanmar, right about the time it was ‘opening up’.

Despite the $1500 SIM cards and the bureaucracy, Myanmar helped me fall in love not just with a country or a region, but with the idea of very hard problems. How will Southeast Asia go from our cash-only economies to online, digital payments? Will women and minorities be left behind? Wobe seeks to answer these questions through the tech we build, via the business relationships we build, and within our team.

We build for them:

(Above, Wobe growth activities in Sumbawa, eastern Indonesia.)

Nothing is constant in emerging markets, except for how things change all the time.

Our community anchors us:

- Empathise: we carry out internal and external research activity to help us make product and business decisions and know our customers

- Understand: we do not assume everyone has a fast internet connection. We know from our research that our customers are price-sensitive, and cautious about data consumption. For this reason, our product (a) has a tiny footprint (b) performs better than most other apps in lower connectivity

- Prioritise: it would be far simpler to use established payment gateways and accept credit cards in-app. Our customers do not have credit cards. It would not make sense to make product decisions that work for only a small percentage of our total addressable market.

Here’s a sneak peek at some of the building blocks at Wobe:

Building the Team

For every founder, the quality of technical team and your technical decisions has a ripple effect. I can’t emphasise this enough. Even when you’re a one-person team, what you decide on this front will have long-lasting impact.

Your main options, pre-funding, are to either find a technical co-founder (a unicorn; stop searching, but more on this later), outsource, or to do it yourself.

Unless you’ve already built products at great scale, and / or run a team to do that, doing it yourself may not be the best use of your time.

For many, the likely choice will be to outsource. All types of dev shops and individuals will be happy to build you an MVP for anything from US$500 to US$100 000. Your mileage will vary greatly. Whatever decision you make on this, do not establish mediocrity as a standard. The quality of your future incoming team, if there is one, will be pegged to the ones who came before. Nobody wants to work with a Z team. Nobody wants to clean up Z-team level excretion.

Wobe’s technical journey was a long one. In the next few posts, I will be happy to share what that was like, how we built a product with very little money, how we thought about technical hiring, how non-technical founders can improve their technical hiring pipeline.

It has a lot to do with first acknowledging you don’t know all the answers. Even if you are a technical cofounder yourself, you don’t know all the answers. Then assemble the best* people who care deeply about your mission.

Our mission is to build tech that works for the people who need to rely on us. We succeed when they are able to increase their family’s income level by a dollar, or a few hundred, because of what we do.

Given the many questions we’ve had to ask, and impossible mountains we’ve had to scale, I want to set a clear path for us as a company. Wobe will be an open company, right down to our core: our code.

In the coming months, my team and I will share how we write Go, how we hire; how we work cross-culturally from Mexico to India and Indonesia; how open source will be a pillar in our company. What is culture?

Culture is not free beer and beer pong. I doubt that anybody really knows what it is.

Let’s find out here together, shall we?

Coconut makes the world, and our infra, go round.

Coconut makes the world, and our infra, go round. Dark, golden and distilled beauty. Just like our microservices.

Dark, golden and distilled beauty. Just like our microservices.

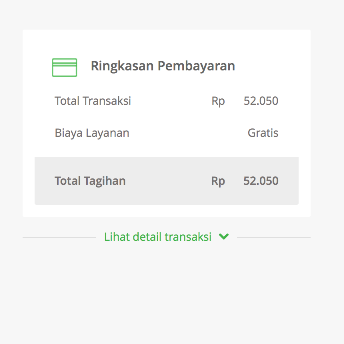

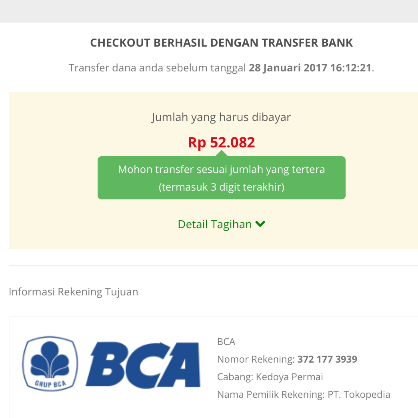

My total, with the unique code (+032) added to the final bill.

My total, with the unique code (+032) added to the final bill. “

“