Posts tagged "india"

← All tags

July 17, 2023

When I think back to the life I led in my 20s, I will be forever grateful and amazed that I got to do the things that I did. How did I figure out how to travel around the world, eating, working, writing, taking photos? I don't think that life exists anymore. Not in the same way anyway. But I really milked it for what I could.

Right out of college, I was a freelance travel and food writer. I wrote about different parts of Southeast Asia. I wrote about chefs. I was interested in history, food culture, people. I still am. But the ways in which I led that life (writing for magazines with "Geographic" in their name, getting advances and payouts from travel guidebooks, selling photos to newspapers), don't and won't exist anymore.

So I continue to do those things, but with a day job.

While I was out on the road, my phone photos were an important 'B Roll'. Today I am sharing a selection of those photos in one place, for the first time.

Chennai was often my first port of call. Whenever I had work in India, I would fly first to Chennai. $100 one way from Singapore. Once there, I deeply explored the world of 'nonveg Tamil food', still one of my favorite cuisines anywhere. That love for Tamil Nadu country food was a love that nourished me and kept me happy. Brain masala, mutton sukka, deeply spiced seeraga samba biryanis. They also called this 'military food', and it was cuisine that was eaten in contrast to the totally vegetarian, 'cleaner' high caste food that I never developed a fondness for. Whenever in Chennai, I ate most at places like this.

Sri Velu was one place that I frequented for this type of food.

Roadtrips across India were a big part of my life. I went on long rides with friends, and one frequent trip was the road trip from Mumbai to Alibag. Vada pavs were mandatory, of course. Till this day, I still dream about the perfect little potato patties, with the right amount of spice, in a squishy white bread.

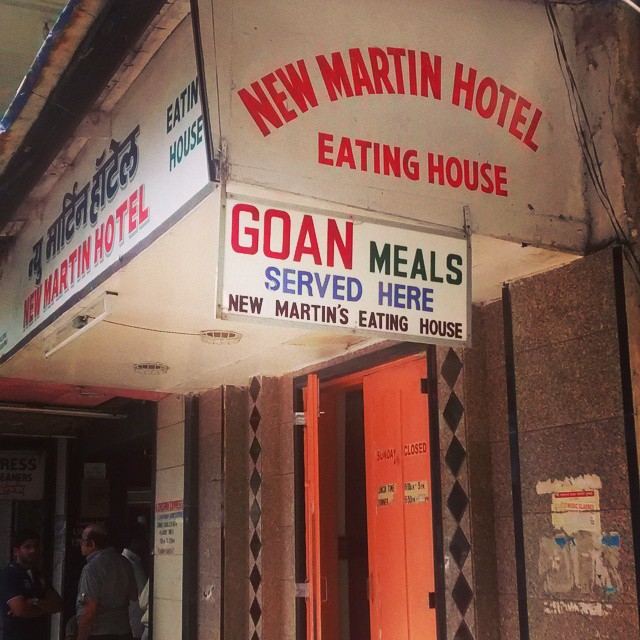

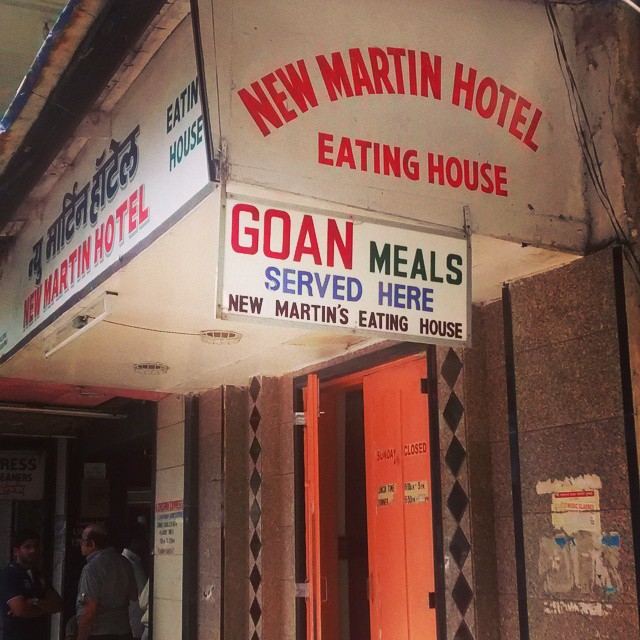

I spent most of my time in either Chennai or Mumbai. These are the two cities that, even today, if you were to drop me there and have me live there for months on end, I would be quite happy. My social circles and my favorite foods remain the same. Goan and all other coastal Konkani food is also a cuisine that I adore. In Mumbai, I frequently went to places like this, as well as to Gomantak or Malvani restaurants.

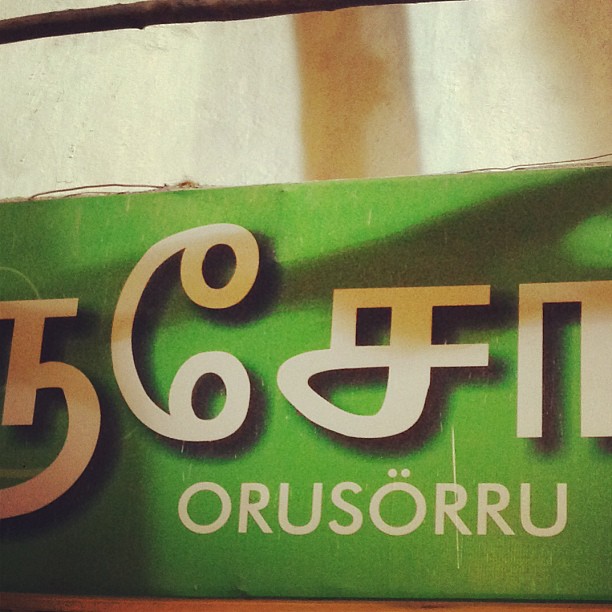

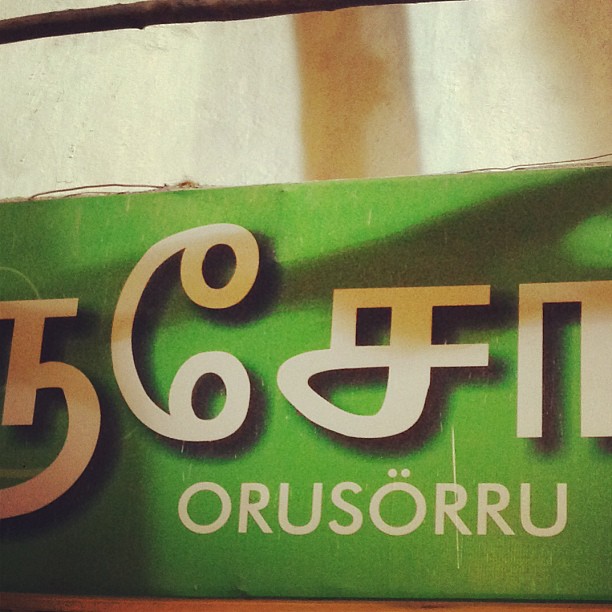

My happiest food memories are always whenever I get to get Tamil style biryanis. Orosorru in Chennai was a fave for a long time, but sadly they are no longer around.

Invalid DateTime

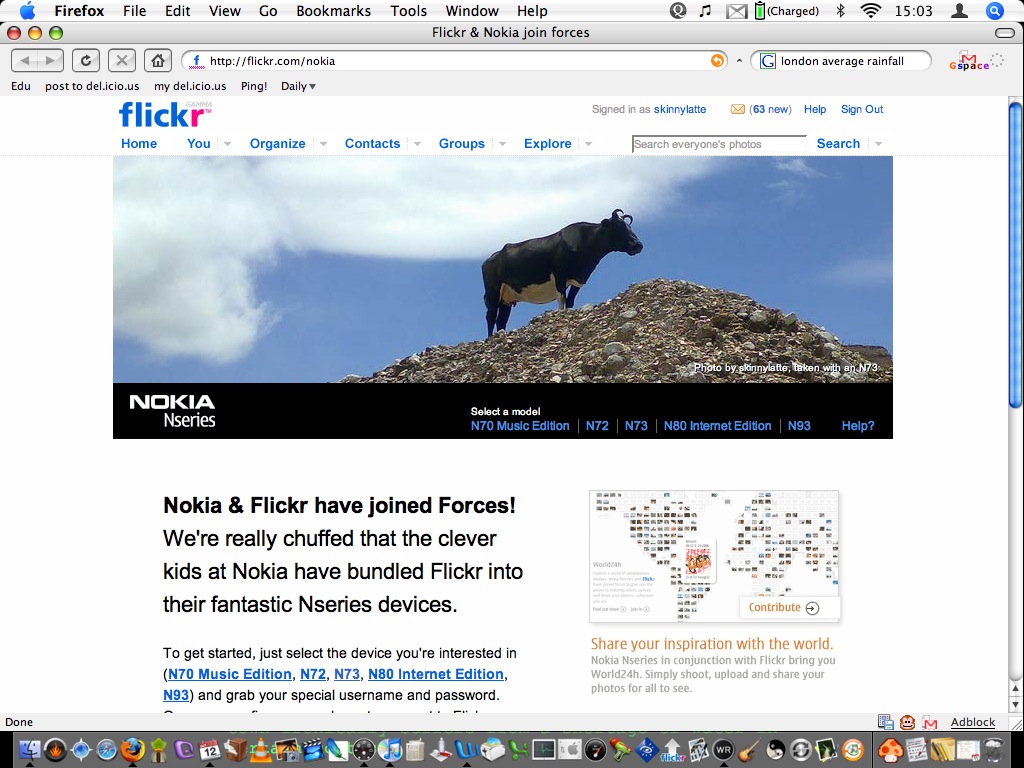

I have been an avid enthusiast of phone photography and videos even before iPhones arrived in the world. To that end, I still chuckle when I think about how in the mid 00s, I not only took cool photos that I still love today, using a Nokia N73, one of them even went on the front page of Flickr for a while!

A photograph of a cow on a pile of limestone. Cherrapunjee, India.

A photograph of a limestone kiln in Cherrapunjee, India.

A sign that greets you as you enter Cherrapunjee.

I had to take a screenshot.

This was the first photography and writing assignment I ever went on. I met a photojournalist in a bar in Mumbai, and ended up collaborating with him across India and Bangladesh. He took the cool pictures (I thought, at the time, as I was less confident in my photography skills and equipment); I wrote many of the stories (which were published by various magazines). We were there to document climate change in the world's wettest place at the time. Not bad for a still-in-college kid (me, then), to have had the opportunity to do things like that.

Invalid DateTime

Most people love the Golden Hour. I also love the moment just before the sun sets where the light changes so quickly you don't know what you're going to get.

A photo of temples at Angkor Wat, some time in 2005. Nikon F-601, not sure which film stock.

A photo of camels in Jaisalmer, India. 2006. Canon 350D.

June 4, 2021

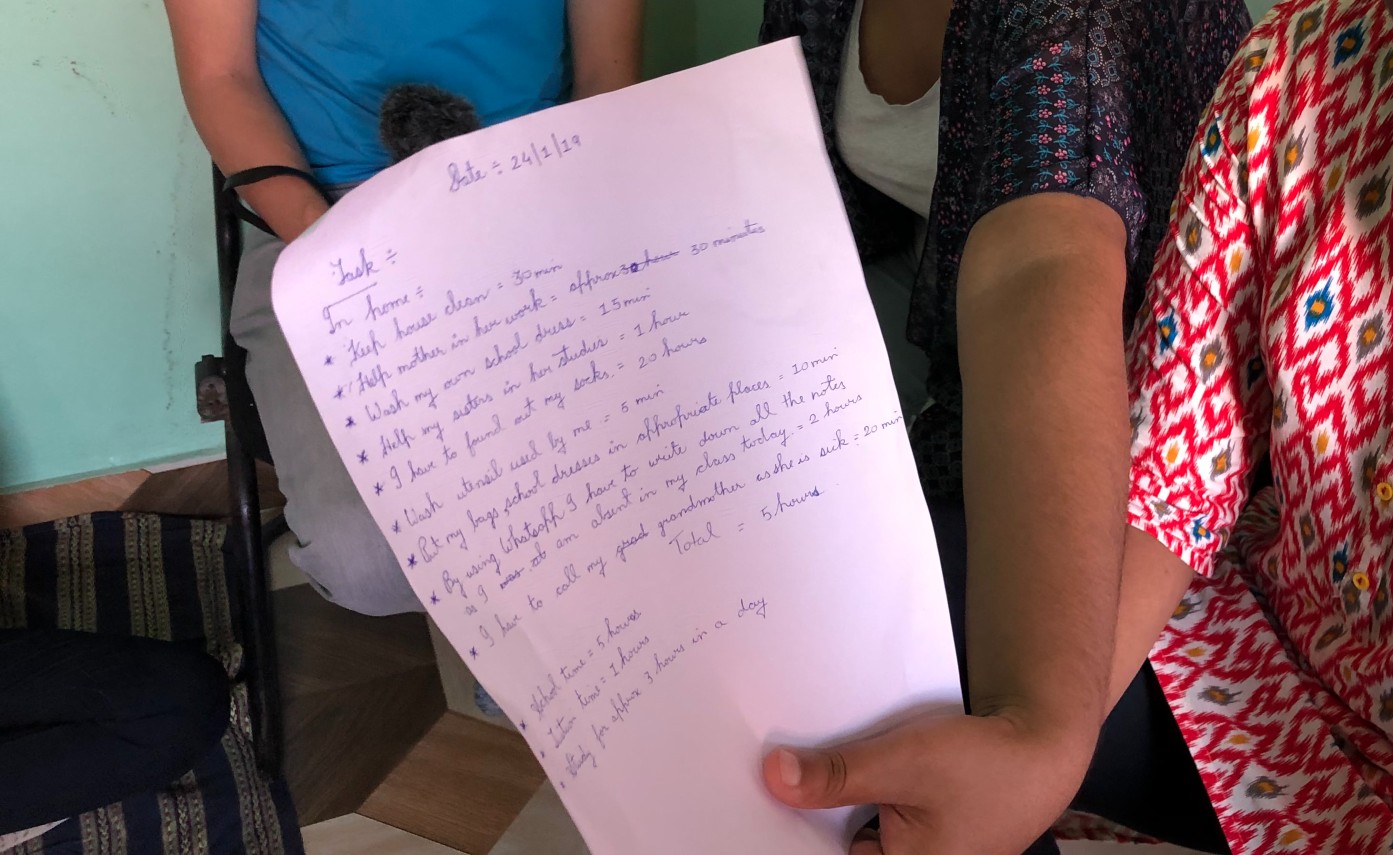

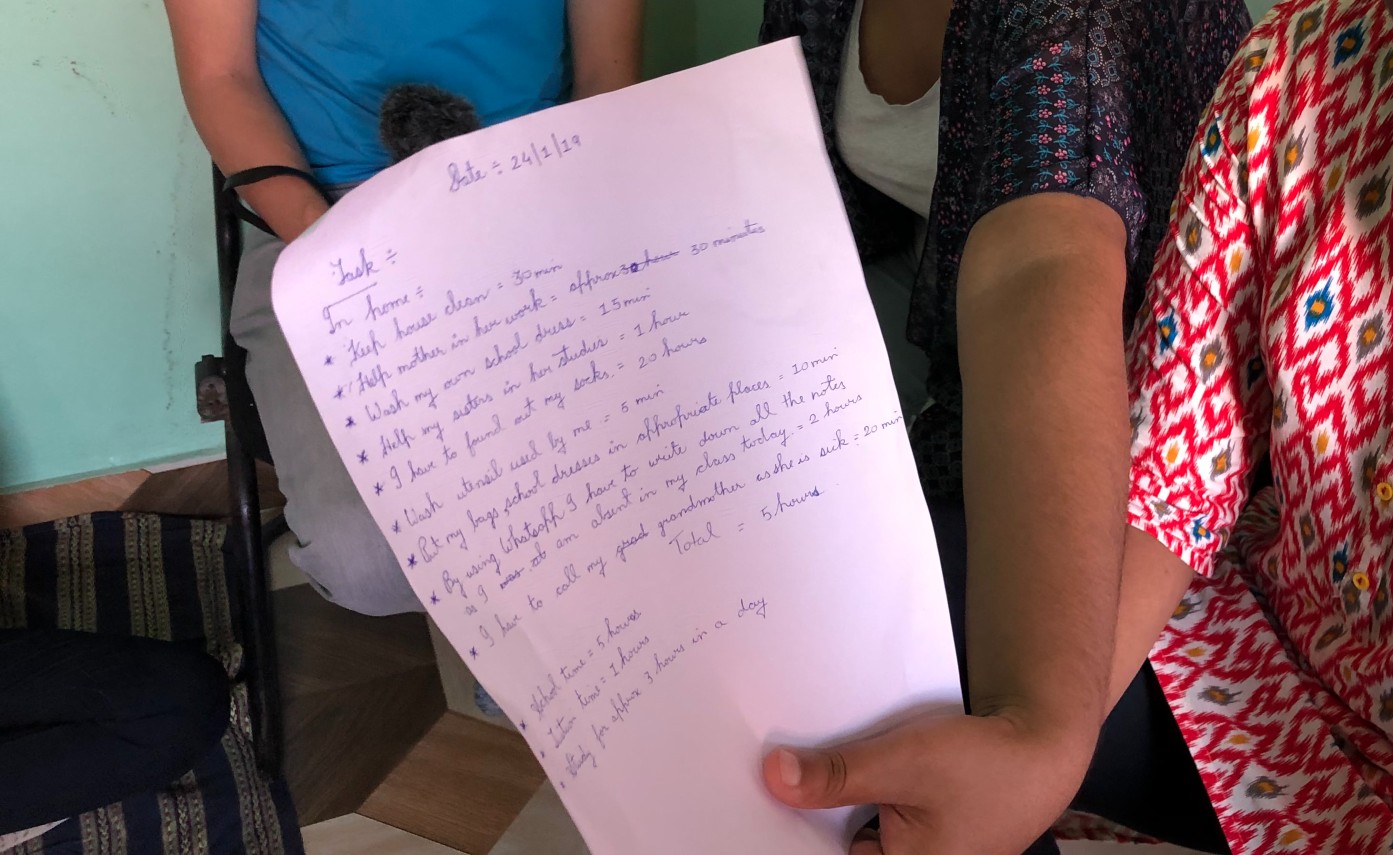

Some of you may know that I have spent the last 9 years or so working to support children's education in Jharkhand, India. In better times I visit them 2-3x a year. I want to share something that stuck with me the last time I went: one of the girls we work with showed us their daily schedule.

Tribal Jharkhand girl's daily schedule (24 January 2019):

- Keep house clean, 30 min

- Help mother in her work, 30 min

- Wash my own school dress, 15 min

- Help my sister in her studies, 1 hour

- I have to found (sic) my socks, 20 hours

- Wash utensils used by me, 5 min

- Put my bags, school dresses in appropriate places, 10 min

- Use Whatsapp to write all the notes I have missed as I am not in class today, 2 hours

- I have to call my grandmother as she is sick, 20 minutes

- School time, 5 hours

- Tuition time, 1 hour

- Study for approximately 3 hours a day

I am nowhere as organized, or as funny, as this girl.

Going to Jharkhand twice a year has always been the highlight of my year. I'm glad to report that the girls are well, as are their families, which is an amazing outcome in spite of the current COVID-19 situation there. I've seen them grow up over the years: they are absolutely committed to wanting a better life for themselves and their families, and hopefully through the work that I facilitate there I can help to open some doors. If you pay tax in India, you are welcome to make a contribution to the team (other options coming, in the.. future. Overseas contributions are very difficult). The local team is amazing and I am so glad to be able to support this work.

May 31, 2016

12 years ago I came to Kolkata for the same time. At the time it was still mostly referred to as Calcutta.

The city doesn't change; but you do.

Every picture I have of it from 12 years ago still looks like it could have been from December, when I last visited. Perhaps even today. When I land at midnight later, there will not be the crisp, muddled air of the winters I love in that city, just the night time counterpart to the heat that I know will pound on my face, and the ground, sometime in the morning.

All that I know, all that I do, I owe it to this city, even if it will never know it.

When my school friends were road-tripping across European cities for summer breaks, or perhaps even the big cities of China and America for work and school, I found solace here. It can be hard to see, but Kolkata is a hard act to beat. It's the ultimate summer. Followed by monsoon. And the sounds of:

It's a monsoon and the rain lifts lids off cars /

Spinning buses like toys, stripping them to chrome /

Across the bay, the waves are turning into something else /

Picking up fishing boats and spewing them on the shore — James, Sometimes (which somehow always comes to mind when I think of this place

How to beat it?

The start, really, of empire. The fall, or rather the fading away, of one. The majesty of India's cricketing hopes and dreams, and occasionally the dashing of, projected unto Eden Gardens even when the matches aren't in season. The death of Marxism, available for the world to see at every adda and every failing piece of infrastructure. Tagore's poetry. Indian Coffee House. The children of Tollygunge, who taught me so much, 12 years ago. Sandesh.

On hot afternoons when the sun hits the ground and meets engine oil, the smell reminds me of my first love among the many other putrid Asian cities I have come to love:

“So in the streets of Calcutta I sometimes imagine myself a foreigner, and only then do I discover how much is to be seen, which is lost so long as its full value in attention is not paid. It is the hunger to really see which drives people to travel to strange places.” — Tagore, My Reminiscences

This foreigner is not done discovering.

Invalid DateTime

12 years ago this time I was deciding where I should go, what I should study, at university. I was also four months away from deciding I would try to be happy in spite of my newfound queerness.

11 years ago this time I was in Kolkata, volunteering with an organization, not knowing I would go on to do that in the future. I was awful at painting walls, and not much better now.

10 to 8 years ago this time on the road learning Southeast Asia out of backpacks I still carried, before my back went bad.

7 years ago this time I got back to Dubai from Istanbul to find beetles had infested everything that I owned in the world. It was the first time I learned you could be truly alone in the world.

6 years ago on the Syria/Turkey border with no money and no clothes. Auto-rickshaws. My first businesses. An annoyingly debilitating illness. Recovery.

Three years ago I was back in Singapore feeling lost and forlorn when I left someone and a city that had spanned half a decade. Two years ago my life of endless pitching had just begun.

Today, 30 and in Indonesia on the cusp of everything. Bring it on!

April 10, 2014

As you may know, I set up The Gyanada Foundation last year. We've spent the past year building the organisation and learning as much as we can.

Last year, we supported 150 girls in India. This year we hope to raise that number to 350, including the existing students we have onboard currently; also expanding geographical reach alongside enrolment numbers at the same time.

Yesterday evening we had a great event at Artistry where we talked about what we've done so far and what we hope to accomplish in the near future.

Here's some information about what we do.

February 14, 2014

At 18 I certainly believed I knew everything. I did not know just how much it'd hurt this boy's heart if I told him the inevitable: that I was in love with someone he could never be-a woman. We went to our favourite bar and sat glumly while he tried to drink away his pain and anger.

At that time it felt as though life simply led me into various unforeseen encounters, at turns dramatic and at others explosive, as if I were but a mere spectator. The woman I loved walked into the bar. I stole a glimpse. I could not look away. Even without saying anything at all, he knew it was her.

She met the man she was to marry that evening after I left.

There was a girl I noticed at the campus coffee shop.

I liked her pants. And her hair. It helped that I sat at that coffee shop every day nursing a cigarette because that's what I did when I was young and stupid. She would walk by, and I would try to find out who she was.

Every day we passed each other in that little corridor or at the coffee shop. I don't remember how, but she agreed to come on a date with me.

We went to a place I still go to, then on a 46-day backpacking trip to India. I bravely led the way. By the second week we were at the Taj Mahal. We had waited to see the sunset because I thought it might be good to attempt romantic gestures sometimes. As the sun set over Agra I reached for her hand. She pushed it away.

We broke up at the Taj Mahal, which was fitting because we had also fallen in love at the Angkor Wat. From one wonder to another, she still could not erase the shame she felt from being with a woman. Even in a country where no one knew her name.

The next 30 days were epic and vengeful, full of sadness and train schedules.

The woman I loved four years ago did not marry the man she met at the bar. I may or may not have had anything to do with it.

The truth was that the more I sunk into the sadness, the more I elevated our mythology. It was not the great love which never was. We were not star-crossed lovers. Not only had I not grown from that point, I had even regressed. Waking up with her every morning made me feel I would lose her any time now. I was a little bit older now but really I was still the awestruck girl in my school uniform and my tie, wanting to know how I could punch above my weight because I can, and God she's hot.

We were the cartographers of silence which began with a lie, later snowballing into a mountain of mythology and characters with their own CliffsNotes and paths strewn with sad poetry and despair and sadness.

When you throw yourself at a wall repeatedly, it's okay not to know when to stop, especially if you enjoy feeling sorry for yourself.

But I had adventures to go on and mythology was too heavy to come along for that ride. I threw it away.

I don't dream very much, but that year I had a vivid dream: I dreamed of a tall, slender woman with a soft voice who captivated me completely in that dream. I felt happy in that dream. I was a new person in that dream. I grew to be a better person with this figment of my dream, in my dream.

When I awoke from that dream I was with such a woman barrelling down the River Skrang in Borneo on a hare-brained plan to see tattoos and drink moonshine with the tribal elders of the tattoo artists we knew in the big city. We hit a rock and the river rushed around us as if it wanted to have us whole.

We went places without names on maps. Places without maps. We were apart a lot, but she drove 300 miles to meet me all the time and we travelled tens of thousands of miles together when we could. I ended up travelling tens of thousands of miles each time I needed to see her, which was all the time. We met in Istanbul. We made video postcards about the places we were in without each other, and we sent them to each other every other week.

Eventually we decided it was time to try to steer our way home.

I don't even remember what home means any more. I had wandered a few hundred thousand kilometres, some of it by foot. Mostly by bus, train or taxi. Even boat.

Home was where she was. Some days it was London. Others, it was Kuala Lumpur.

I found a little house I thought we could be happy in, got a dog, and perhaps for a time we were. It feels as faraway as all of my 18-year-old memories.

I don't remember when I stopped trying. I was back at the Taj Mahal again, and everything about that monument still fills me with despair. I'm never going back there ever again. I looked at her. I felt despair. I didn't know how to fix us. I just stopped trying. Or talking. I held her hand on a cold New Year's Eve in Jodhpur. I felt nothing. I kissed her. She did not want to kiss me back. I fell asleep with my back turned, full of anger and secret tears. It had been that way for a while now.

A few months earlier I asked her to marry me. I was met with nervous laughter and panic. In hindsight, it was a bad idea. Everyone knew she would say no.

Except me. Ever the optimist.

The computer says no.

Everybody knows it. But I didn't get the memo. It was always no.

--

I've been thinking a lot about what it means to be a lesbian in this society, and it all comes down to this: other people. It's that I have to automatically assume that all of the following are bonuses, not expectations: having my love recognized for the purposes of property, tax and inheritance; attending a partner's family functions without unnecessary outcry and suspicion; knowing that if I were to be in a medical emergency, my life partner would be legally allowed to make decisions on my behalf. In other words, to even hope for my future life partner to be perceived as anything other than a complete stranger, is going to have to be taken on other people's good faith.

As outsiders, that's all we have to go on: the goodwill of other people. The readiness of other people to stop thinking of us as criminals, sexual deviants and perverts. If I hold hands with a woman I love, I am rubbing it in a conservative society's face and being too declarative about my sexual orientation; if I walk side by side with one, the man who catcalls and makes lewd comments at us bordering on sexual harassment, is just, after all, being a man and is entitled to his opinions about my body and hers.

As for someone who generally feels like there is nothing in the world I cannot do, all I can do is to keep on doing what I do best-live my life as best as I know how, be kind to old people and animals, donate to charity sometimes, avoid premature death-and dream about the day I hope to see in my lifetime: when our lovers will be our equals, and our love as deserving.

February 7, 2014

-

Almost exactly two years ago I was, too, on a flight to India.

Only then I did not know exactly how drastic a turn my life would take on when I returned.

-

More and more of my friends are getting diagnosed with diseases similar to mine. Autoimmune diseases are the new black.

Across all of these experiences the one we've all had has been the extreme upheaval in all of our emotional lives.

-

Sometimes I wonder if the person who made those decisions at the time was me, or the severely impaired bodily part that's wreaked havoc in my head and my heart.

Even if the conclusions are the same in the end, I would still like to know that I had some control. But I did not.

-

There is nothing I hate more than feeling like my self-determinism, even if it doesn't really exist, has been impinged upon.

Even if the other person making decisions for me was just a temporarily damaged version of myself.

-

I've spent almost two years rebuilding my life.

I've subjected it to some pretty extreme versions of what it could have been and can be, and now I've chosen the version I like best.

I like this one.

-

This one:

This one is happy and confident, pushing 30.

This one is writing more, and better.

This one has had a handful of career highlights and is working harder to create the sorts of situations and opportunities that will define the next decade; it's within grasp.

This one has an incredible support system in Singapore, Malaysia, India and all around the world and feels like the luckiest person in the world to experience such love.

This one has a loving family. A beautiful dog. A lovely house in a magical part of the city that she loves more and more. A slew of projects taking shape.

This one is learning to finish what she's started.

-

I've struggled to articulate what I feel whenever I return to the city I once lived in.

It is a living museum of my loves and losses.

It is a diptych where one side is the city that I once knew and the other is the one I no longer do.

Time has stopped for me in that city. But I am learning to love it again after.

-

The city that is a living museum of love and loss merely preserves them so I can learn to love again.

The streets I walked in in them will never be the same.

Just as it should be possible to hold two opposing positions at once so as to form a better informed opinion, so too should it be possible to hold multiple feelings simultaneously so that we can love better.

For now I pick: terrifying, amazing.

Life's too short for compromises. I'm too fond of jumping off boats then learning to swim, anyway.

February 3, 2014

I've been coming and going from India for the last ten years.

In 2004 I started to hatch the first plans to flee the terrifying life laid out for me - that of a student in a Singapore university, doomed for the corporate world or for the civil service - into the wide open arms of India, which changed everything, and who I have grown to love unconditionally. Those early escape plans evolved into a lifestyle I would not trade for anything in the world, one which has given me ample global career and life opportunities simply because I could not sit still when I was 19.

I've written a lot about India in various forms, but here are some posts previously posted here about India:

Speak of India and its great cities, and someone is bound to correct you.

Mumbai, they say, offended, as though you didn't know any better. In other situations, Chennai. Yet I do say and I do like saying Bombay and Madras because those were the names we had for those cities, growing up a sea away from the subcontinent, and nostalgia counts for something, nationalist political correctness be damned.

It's a weird question I cannot answer whenever someone asks the inevitable, why do you love India so?

Where do I begin?

Do I begin with the story of how hearing my China-born grandparents conversing in market-Tamil with our Tamil neighbours as a child mesmerised me whole, leading me to watch Tamil movies endlessly wondering why I could not understand the dialogue?

Or perhaps it has something to do with how I was born a stone's throw away from Little India, how my parents were wed on Diwali, and for the astrologically-minded - of which I am not - that made perfect sense to explain away my identity confusion? My solo walks around Little India as a teenager led me into informal Tamil lessons I can no longer remember, and spice shop tastings that made me feel, for once, that this is a home I understand? _

_

Or that nearly all of my early mentors in childhood and adolescence were Tamil-Teochew poets and Sanskrit scholars who imparted in me a love for rhyme and meter and an irrational fear of booming voices; that later in life, nearly all of my friends, lovers, business mentors and collaborators would also be connected to India in some way or other?

None of that matters.

What does is that in 2004 I walked out of the airport in Calcutta and felt immediately that I had come home, through no other prior connection; and that every year ever since I have returned, twice, thrice, and more each year, sometimes staying for months.

Whenever I read travelogues about India I am often unable to understand why the authors keep writing about the Indian Arrival Syndrome: something about throngs of humanity and masses of people and rotting flesh and cow dung and about needing to flee. The only time I have ever felt that way upon arriving anywhere has been in the great cities of America and Europe, where I have arrived and thought: oh my god, where are all the people? I need to leave. (Eventually, I got over it. But I certainly don't write travelogues about arriving at places I don't know and wanting to leave.)

I love that I am at home in Madras, Bangalore, Calcutta and Bombay (I'm only just learning to like Delhi). That I have my secret places, amazing friends, and a world of possibilities. If I want to drop in on a film set, I can; if I want to organise a great conference, I can; if I want to do business, I can too; if I want to set up a foundation and educate a hundred and fifty girls, it's possible as well. I am aware everyone's mileage varies, including that of the people who actually live there - but that's just how it's been for me: it gives me an imagination. Mostly by showing me the extremities of the world.

After every breakup, illness, death in the family or other assorted tragedy large and small, my first instinct is to go to India - anywhere in India. It works. It's been called my Prozac, but what it is is really far simpler. India is where I go to make sense of the world when the world no longer makes sense for me. That arrangement has worked so far, this past decade.

I'm excited about what the next five or so Indian decades will bring.

June 8, 2013

As many of you will know by now, I have spent a substantial part of the past decade travelling through India. I still feel like I'm barely done with scratching the surface. There's just so much to see in that vast, amazing country that I call my second home.

For some time now I've wanted to go to Coorg.

Coorg, also known as Kodagu, is a hill area in the state of Karnataka, in the Western Ghats. Its people are known as Kodavas (not Coorgis!) and all I knew about the place was that it had coffee, beautiful people, and pork curry. All that was sufficient to inspire me to plan a trip there.

From Chennai, I took a quick overnight train to Mysore Junction (book early, book ahead — this route is headed towards Bangalore, and therefore sells out early), but you can also take a bus. At Mysore Junction, I arranged for a car to pick me up for breakfast and to my resort of choice.

An acquaintance from Mysore highly recommended Travelparkz, and he was right: they were a very reliable car and driver service, and it was good value. I hired them for a pickup from Mysore Junction railway station to the resort in Coorg that I was headed to; and for a drop-off from the resort to Bangalore city a couple of days later. I highly recommend these guys, though it's best to reach them via phone. They speak English.

I had heard about The Tamara from friends in Bangalore, so I decided I would give it a shot. It's a very new place and it gets most things right. My only complaint is it didn't have as much pork as I would have liked.

You can wander about the grounds of The Tamara on your own, or sign up for one of their daily walks with their on-site naturalist. I did none of the above as I was too busy resting after a long week at work in India!

Highly recommended. I will be returning to Coorg shortly, although I may want to check out Victory Home next, since I've just met these guys in Bangalore.

Damn I love this country.

The path to my cottage

Happy feet

All rights reserved, The Tamara Coorg

March 12, 2013

I've thrown myself headlong into work — real work, and then foundation work.

India is an important part of my life and I owe everything to her. Over the past couple of months, my friends and I have been busy putting a little NGO together, the Gyanada Foundation.

Today (Tues, 12 March) between 7 and 9 in the evening, I'll be hosting our soft launch at Artistry, 17 Jalan Pinang.

Here are the event details! Hope to see you there.

January 28, 2013

I have a tattoo on my lower back. It was given to me by the grandson of a tribal village chief. I grimaced for hours on the floor as he used the primitive tools and ingredients that had tattooed his Iban people for centuries, on me, a girl from a big city.

I'd always wanted a tattoo, but didn't know what; this one crept up on me. Like the girl I was there with (we had a crazy idea: we would visit and live with an Iban community in a longhouse and celebrate Hari Gawai with them), I wasn't expecting any of this. The girl, the tattoo, or that I would have such a story to tell many years after the fact. I chose a bunch of tribal motifs from an album and told him to make it up. I got lucky: I like my tattoo very much, even if it is what some people would call a tramp stamp. I'm proud of it. There's a story to tell each time anyone asks about it.

The girl is no more in my life but the tattoo remains, defiantly representing all of the new beginnings I will embrace in life. Tomorrow, I start a new life and more and more I feel as though the year of grieving and floating, which so profoundly altered my path and direction in life as well as my livelihood and future plans, is finally about to draw to a conclusive close.

I am finally ready for another tattoo. This time, I know exactly where it should be, what it should say and what it should look like. I would not have known this without the pain of my first tattoo. It will be a beautiful Sanskrit verse from the Bhagavad Gita and I intend to have it inscribed on my upper left shoulder. This time, I will harbour no plans or illusions about the permanence of anything other than that of the Sanskrit verse on my shoulder; this time, I will learn to love without needing to know the world.

June 22, 2012

Five years ago, I said: "Ask me again a year, three, or five from now and all I will remember is driving up, around, up, around, up, around, in the swirling clouds as the rain lashed at my windows and I feared for my life, balanced so daintily in this tin can navigating itself on the hairpin road."

Plenty has changed, these five years, but at least this part remains familiar: "Ask me again a year, three, or five from now and I will still tell you the same thing: I’m not sure why I do the things that I do." Then, I was referring to the heady, exciting days of a student who had the chance to criss-cross across the hill tribes of northeast India and investigate the ailments of rural Bangladeshis suffering from leprosy, TB and lymphatic filiarisis. I got to go on the amazing adventure of my life, never really expecting it to end. It hasn't.

Much has changed, but adventure has never left me.

The last five months have been tumultuous. It was the sort of chaos that was ultimately a blip in the universe (though still a large one), and not, thankfully, the sort that led to destruction and the end of the world as I knew it.

In a few days I will make that trip to Kuala Lumpur for the last time. It will be awkward. On it, I will return to the apartment I've had for two years, but haven't lived in for the last five months, and I will assemble everything that I own in that city and that country, and pack it into several boxes. I last packed all the things I owned in the universe into several boxes under far happier circumstances. This time I pack a dog into the car, too.

I don't regret a moment. Life has dealt me a pretty good lot, and I have milked it for what it's worth. So from Singapore to Dubai and the Middle East to London to Kuala Lumpur I now find myself surprisingly, but not that much, in Singapore. I left a Singapore I didn't like very much, and returned to a Singapore I absolutely love (there's an essay in that somewhere). You can't come home again, but you can definitely make it home again, for the first time.

The single life is interesting, but difficult, in equal parts. I haven't dated in such a long time, I really don't have it in me anymore.

The life with hyperthyroid is worse.

I can't remember shit. I quite literally feel like I've lost a major chunk of my former cognitive abilities. It sucks.

How am I dealing with all of this? I'm… dealing. If you know me in real life, you probably can't tell. I've worked very hard to keep it invisible. My heart rate still goes nuts. I drop a ton of weight or I put it back and I drop it again. I am manic and then I am exhausted. I am utterly intolerant to heat, even in an air-conditioned room I am hot. I don't need any medical diagnosis here (I am actively under the care of the medical professionals here, no worries). I just wish I could get my memory back. I've gone from one of those people with super memories to one of those who has to scribble down everything. I don't remember people I've just met (this has never happened before), I don't remember even meeting them, most of the time. It's amazing I can even work at all.

The last five months have felt like a massive blur. I feel like time and space has compressed for me. Or that I'm living in a time warp, splitting myself between two universes. One: pre-illness, pre-breakup, pre-everything. When life was, I thought, sorted. For the time being. The second one, the one I inhabit right now: plagued by a disease that doesn't threaten but bothers me, learning to find my feet again without the woman I love and the life and businesses we had. Breaking up gets more and more expensive as you get older.

I'm okay, I'm good, I'm pretty happy (seriously) — I was just telling someone that I thrive in change in ways that many people don't understand, but I do. Change works for me.

I should be more careful what I wish for, you know? Now there's so much of it I am still finding my feet, but I'm not sure how. That suits me fine for now.

It's just that I hate packing.

February 1, 2012

A note from New Delhi

Taj Mahal Foxtrot, namesake of the book by the same name by naresh.fernandes

Another new year, another bad habit: I'm late, again.

Just a few days ago, I was sitting at the back of a Toyota Innova, stuffing my face with mithai and chips — not at the same time — thinking what a nice surprise it'd be for my readers, to finally post, and on New Year's Eve, too. I didn't make it. I got busy.

The landscape outside my window was of rural Rajasthan: familiar. Not as brutal as the Marwar I came up close to, the last time I was here, at the peak of summer. Not too long before that I had arrived in Rajasthan with my young traveller tie-dye pants, led by nothing other than the youthful desire to do something unexpected, terrible and difficult. Things are quite different now: I have a ‘job' to get back to. No doubt it's a business I own and run, but I still can't get away for as long as my college summer breaks allowed me to.

Everything feels different. Only India feels the same.

This winter made Rajasthan different from the last. It was much better, with its cool — almost too cool — air, dry spells. Not quite as cold as Delhi.

Hurtling through traffic, avoiding cows and camels, stopping occasionally for a ‘sulabh' break — BYOTP (Bring your own toilet paper), the Innova, the "metal cow" of the Indian road made its way through all places familiar and strange.

We made a makeshift cinema on the rooftop of the small bed & breakfast we were staying at, shivering in the cold under bundles of blankets, with a dazzling view of the Umaid Bhawan in the near horizon.

We drank copious amounts of lassi.

We ate, drank and made merry — with our hands, of course, for to eat with a fork and a spoon is just like making love through an interpreter.

We didn't break up at the Taj Mahal.

I'm in a different place now. A good place.

Not too long ago I was hopping around some parts of the world on a series of one way tickets, with nothing to hold me down to any place or any one. Just me, my backpack, my cameras, notepads, my lone self in a hostel room for one, on the lonely (but fun) road to self-discovery. That part of my life seems to be a distant past now. The places are the same but the package is different. I could not go away for a year now, not without looking back wistfully at some people, things and creatures.

The things that bind come when you least expect it.

They were the crazy thoughts that slip into your head when you meet someone for the first time — at a bar, or at least that's how it was for me. The furious back-and-forth binary exchanges through various electronic sources. A text. An email. A few stamps in your passport and many flight tickets later, and you're settled. Sort of. Settled as far as you can be. You go to a city, rent a house, set up a business, own a dog, and suddenly you're one of those people boring hippies to death about how you love Singapore because you can go jogging at three in the morning and feel safe. Suddenly you're one of those regular people who can go someplace breathtakingly beautiful like the Taj Mahal and feel nothing except annoyance at the incessant crowds, and you're not the sort of girl who goes to the Taj Mahal and breaks up with the person next to you anymore.

No one ever tells you it's going to get better in your twenties.

They don't. Okay, so you can drink Yakult everyday before lunch and after lunch, and nobody tells you you've gotta eat a vegetable. That's where it gets tricky. No one tells you anything — you're supposed to know. About everything. About salaries and savings. About weddings and funerals. About businesses and jobs. About children and insemination. About… everything. It's up to you. You can drink as much Yakult as you want, but if you lau sai, you take yourself to hospital and you pay for your own medical bills. You can go through life never eating a single vegetable if you don't feel like it, but when you're constipated… well, never mind.

You amble through life, finish college, and if you're lucky, acquire some sense of purpose — I like to think I was lucky in that department — and then you try to make yourself a success. Somewhere along the way, one of your friends is going to die in an accident, another one of your friends is going to be diagnosed with a terminal disease, and there's going to be absolutely nothing anyone can do when faced with sudden mortality: something most of us have not had to think about until now.

I'm not sad or anything like it. Quite the opposite. I love what I do (btw, it's a combination of writing, speaking, and separately of selling and making apps and running a small company that makes apps), I wake up every morning the master of my own time and location — which is something I established a long time ago as a bare minimum for any endeavour. I will be where I want to be, when I want to be. This has meant 800km trips up and down the North-South Highway every other week, crazy meetings packed in rapid succession, and some sort of invisible third arm growth that is my iPhone and high speed internet connection.

Some mornings, though, I wake up missing the part of me that's long gone. That part of me that used to write furiously, take good photos, chase stories, pursue any trail of human interest in my vicinity. I'm not complacent or anything: I've just lost it. Like not knowing how to play a piano again from neglect, despite banging on it for 10 years: I've just lost it. I've lost my need to go to places, see things, talk to people, take photographs, write stories. I've lost my wide-eyed curiosity and innocence — I've seen it all before, my brain tells me, and there are precious few things in the world that leap out at me the way everything once did. Absolutely none in the developed world, which doesn't interest me anthropologically or culturally in any way, and a dwindling number in the developing world. India. Yemen. Syria. Places like that — full of raw energy, waiting to be unearthed. And in India's case, ever-surprising and ever-ready, no matter how many times I go back there.

Then there's the writing. Not having had the discipline, time or desire to write as often or as much as I once did, the year or two of utter neglect is leaving me scrambling to pick up the pieces before I lose it forever. It's difficult to keep writing when you've been stuck, as so many writers before you have been, on that one debut novel you've been hacking away at for years. On the bright side, I am at a better place right now to write — and finish — that novel.

So the point of all this, I guess, is to figure out what's next? Lots.

There's that book to write. Like an awesome Chinese soup on slow boil, it can't be hurried. I'm just doing what I know best, although I should know better. But that's for me to figure out.

There's the business, which appears to be growing. I've had the good luck to work with great people, so I'm excited about what it's going to bring in 2012.

Then there's the travel. I've been lucky to be able to visit all these amazing places and to know a few of them quite intimately. There's plenty of travel scheduled for 2012, some work, some leisure, and I may finally be able to get to a few places I've dreamed of going since I was a little girl. Places that were difficult to get to.

On the home front, my resolve to spend more time with my family in Singapore appears to be going well. On the home front in KL, we're at a good place although there are some plans (on my part) to move back to Singapore at some point this year.

I don't know. For someone who hates planning, I've certainly planned too much. Always the big picture, the big goals at the end of the line; never the small details. Maybe it's time to think about the details, too.

Health-wise I'm in pretty good shape. I'd let myself go — so typical of a long-term relationship — but I think I'm back at a healthy weight, build and BMI. Never again. Although the rapid and massive weight loss means I need to shop for a wardrobe anew, it's a step in the right direction for 2012!

I won't bother with setting any resolutions since those so often disappoint. Let's just say I have my eyes on the prize… or prizes! Lots to do, lots to work towards — a combination of company work, personal work, and community work — and I can't wait to get started. Though I'm currently nursing a flu from the brutal Delhi winter smog, I can feel it in my bones that 2012 is going to be a year without precedence, one that will blow the last 5 out of the water (and I've had very, very good years recently)!

Also, I've been going back to India really, really often. That counts for something in the greater scheme of happiness. Happy new year, everybody.

April 15, 2011

Thiruvannaamalai to Yercaud, 155km, though it ended up a lot more

I come from a place with no highlands. No real ones, anyway — the highest point, Bukit Timah Hill, is a mere 163 metres. Enough for families and joggers to work up a sweat on Saturday mornings; not quite enough to keep going. You run, you jog, you break up a tiny bit of sweat — then it's time to "descend" for breakfast at the nearby hawker centre.

Not so in India. Home, after all, to the Indian Himalayas. My first time in India was magical, and one I will never forget. As a naive amateur traveller at the time I had mistakenly assumed all mountains were the same. I had only experienced winter, once, in Mount Sorak in South Korea. I remembered four degrees Celsius was quite doable, even without too many winter clothes. I packed just as light, then, for the Indian Himalayas. On reaching Darjeeling I realized what a mistake that had been. This time, I was no newbie: I had been to India about fifteen times since, and knew a thing or two about its disparate climates. I also knew a little bit about its hill stations, and its rickshaws. Something in my body — common sense? — also told me it might be a bad idea to climb a hill station in an autorickshaw.

One of the things that people who know me are likely to say is that I like to do the very things that I'm told would never work.

Like driving an autorickshaw up a hill. Remind me to never do that again.

The last we ever saw of our route book.

The real story began the moment we left Thiruvannaamalai. The breakfast briefing made it seem easy enough. Take off at 8am, get lunch somewhere on the way, meet in Harur to make sure everyone was on time, meet again somewhere near Pappireddipatti so we could time our ascent uphill together.

Andrew and I were to get horribly, horribly lost, that day. For the first — and only — time.

Karthik left us that morning in Thiruvannaamalai for Chennai. Having just obtained his PhD days prior to the race, he was slated to move to Brussels soon after. Due to some bureaucratic screw-up, he had to bus it back to the capital for a medical appointment for his Belgian work visa, then head back to meet us in Yercaud that night. Not having a Tamil-speaker onboard was doable, but my team had gotten used to the idea that we could muck around after flag-off, have breakfast, hang out with locals, see a few sights, then start moving.

Flag-off at Thiruvannaamalai was as uneventful as it could be — I could not wait to get out of there. Karthik bid us farewell even before we woke up. When Andrew and I got to base we were pretty sleepy, still, having spent the previous night sleeping on terrible beds (and I on the floor). When the horn sounded and all the teams started for Yercaud, we headed to the nearest coffee shop to eat a quick breakfast (muruku and some other snacks) and to take swigs of coffee before we started properly. It must have been 8am, usually an ungodly hour for me, but the faithful were already awake.

Hungry, we had kothu parotta in Kambainallur.

At the coffee shop near a temple on Chengam Road, we looked quizzically at the legions of old, white people in "spiritual clothes". I looked even more quizzically at the firingi prices we were obviously paying here for muruku and kaapi. We read the newspapers, chatted a little, then with some reluctance got back into our rickshaw to begin the drive. Still no clue what we were in for. You know how some mornings when you wake up you drag your feet and don't want to go to work?

That morning I woke up and dragged my feet and didn't want to drive my auto. Off we went anyway. My job, since I was no good with driving these things, was to sit in the backseat and navigate. My tools? Google Maps on my iPhone. Google Maps in this part of the rural world was fine — if by fine you mean, places, villages, towns and cities actually show up, in English. The directions they came with were impossible. Being from the big city, you understand: if Google Maps screws up, it is the end of the world as you know it.

So we followed these maps on my phone, and the navigational directions they gave us. Except that we got hopelessly lost in the end. We kept going anyway, and the people we'd stopped for directions were no help. "Which way to Harur?" This way, that way, you go straight there and then you turn left… India is a pretty bad place to get lost in. Everyone wants to help, and does; except when you're lost, all that help is really no help at all. At a petrol station we got the usual "OMG, foreigners! Driving a rickshaw!" curiosity. And still no worthwhile directions. We kept driving, driving, following one lead after another.

We passed lots of farmland, and lots of construction. We drove over bumps, we drove on very awful roads. We found ourselves in a village where I got out, and gesticulated wildly. Yercaud! Yercaud! Which way? (Making a note to myself that I should have paid attention to what little Tamil was spoken around me, growing up.) "There!" — followed by the Indian octopus. The one where at least eight arms point in eight separate directions. If you're a newbie you end up following directions given by the person who made his case most forcefully and most convincingly. If you've been around these parts, it's that guy you learn to ignore. We kept driving, in some direction.

With another happy passenger. Fare: zero rupees.

More farmland, more cows, more farmers and more awful roads. The lead we had followed previously now led to what seemed to be a dead end. I jumped out of the rickshaw and gesticulated wildly. Is Yercaud back there — pointing at the direction in which we came from, so at the least we could find out if we were going in the wrong direction — or that way? Nope, all the answers came fast and furiously. It's the other way, just keep going.

I was driving on one of the smaller highways, emboldened by how easy it was becoming, when the highway suddenly led into a town, and the town led to lots of people. Remember, I don't really know how to do this — I'm just not good with manual gears, not yet — so I suddenly felt I could not control the rickshaw, and it was cruising along at a speed that was much too fast even for an small town. Andrew, who was chilling out in the backseat, was starting to realize this too.

I kept going anyway, freaking out and yelling "ANDREW I NEED YOUR HELP!" but by the time he scrambled and leaned over to take control of the gears, the rickshaw had already hit a motorbike. There was an old man on it. He fell. I felt like everything that could have gone wrong already had — and yet here we are, about to be in the middle of a large mob with possibly no way of getting out of it.

True to my projections, a large mob had formed around us and the old man. But they were not yelling, nor were they demanding anything. They gathered in large numbers but then some of them helped him up from the ground, another group picked up his motorbike and brushed off the dust, and others yet just stared at us. "It's okay, just go," the mob was saying. But I knocked over someone's bike and it's possibly not working now! "No, he's fine, you should get on your way." I tried to give the old man some money to fix his bike. He shyly refused, acknowledging the power of the mob around him. They were so nice to us, almost to the point of assuming that we must have been so unlucky to have had a tiny accident here in their town, even though it was my fault, that I felt embarrassed instantly. Knowing I could not out-talk the mob, not in a language I didn't speak, and not wanting to embarrass the old man either by insisting openly that he take my money for his bike, I made it seem like we agreed, gathered our stuff, and got back into the rickshaw. But not without shaking the hands of the man whose bike I had knocked over (even if it was gently so), and pressing a small wad of cash into his hands. We took off then, and kept going.

Then the phone rang. It was Aravind, wanting to know where we were — everyone had already assembled somewhere for lunch — so where the hell were we? Ask someone, he said. With no Tamil between Andrew and I, and sign language not cutting it for when actual explicit directions are required, I passed the phone to someone who spoke in Tamil to him.

When I got the phone back, Aravind calmly told us we were at least two hundred clicks in the opposite direction. Please drive back towards Harur ASAP. Still the villagers pored through our route book, and were unanimously convinced we just had to keep going, there would be a turn, go up that hill, and then it'd be Yercaud. I could see it, and I wanted that hill to be Yercaud, quite desperately. But of course it wasn't.

So we doubled back and drove off in the other direction.

One hour. Still no sign of Harur. We were, instead, in Kambainallur. This being a good-sized village, and by this I mean there was actually a place we could stop and eat a proper meal in, we parked outside a little hut where I saw something I recognized. An iron griddle. With food on it. Food being kothu parotta, one of my favourite childhood foods. This far out from home, and from the places I knew in India, having something close to home like kothu parotta was a wonderful feeling. It reminded me of all those nights I walked from my university hostel in Singapore to Little India to eat parotta, chopped up, with egg and chicken. I decided I would have the same thing right here in Kambainallur just so that I could feel we might somehow find our way to Yercuad later.

The people at the restaurant were bemused, to say the least. When I think of rural Tamil Nadu now, I will forever remember it for the sweltering, still heat beating down on our backs. No wind, no breeze — just the slow oscillations of a very old, very dirty ceiling fan. Tic. Tic. For half an hour we ate our tasty kothu parotta in the hut, and entertained the people of Kambainallur who were coming into see what we were up to. Yes, we are driving this thing…

I'm often asked, wasn't it dangerous? Dangerous, to the extent of possibly damaging life and limb on the road, yes — theft and other crime, not so. We usually parked our auto somewhere in sight. By the time we were here in Kambainallur we had gotten so comfortable in this part of Tamil Nadu we even experimented with leaving our bags of expensive camera equipment in the rickshaw, although well-disguised. Every single time we — as foreigners in this part of town — were treated with far more curiosity and amusement than anything we owned (which probably didn't look like very much, considering how we were dressed).

We clambered back into our rickshaw with a small post-lunch stupor, armed with cold Pepsi and Thums Up, and took off somewhere into the distance. This time we had a small feeling we might be on the right track. We kept driving, and noticed people were trying to flag us down. This time we were in the small country roads that cut through the villages, not on the state or national highways, and not on the larger arterial roads between the towns either. There did not seem to be any public transportation — nor any other autorickshaws — around for miles. We decided since we had just had a small spot of good luck (with the tasty lunch and finally figuring out which way to go), we would pass on the karma. We began picking up passengers.

All of them were going a short distance, usually to the next village, so each ride lasted an average of 10 minutes.

With our music thumping in our rickshaw, food in our bellies and cold drinks in our hands, Andrew and I started feeling rather invincible. We stopped for every single passenger who flagged us down. Each time, happiness as we drew to a halt, then confusion, horror, as they looked into the vehicle and found us looking like that. They all climbed in in spite of the incongruity. Not knowing how to speak with them we simply drove on straight, and they told us when to stop.

Lady we gave a ride to in Kambainallur.

First, an old lady near Kambainallur who wanted to go to her sister's house. She climbed into the backseat with me, her orange sari so long it flapped into my lap. She was mostly silent, being rather shy as some rural old ladies can be, only using her hands to direct how we should go to her destination.

After a few minutes, her curiosity got the better of her and she asked, in Tamil (which I understood a very limited amount of), "Where are you going?"

"Yercaud."

"By rickshaw?"

"Yes. From Chennai."

"Why didn't you take a train? It's so much faster."

With that, she pointed to the village she wanted to alight at, and ran off into her sister's house. I often imagine what she might have said to them. "I came here to your house in an autorickshaw, driven by an American and a Singaporean, and they were dressed like rickshaw wallahs." I often imagine that might have been the rural equivalent of saying you just saw a spaceship.

We kept going. We picked up at least four people, each of whom was just as incredulous as the last. One man had huge gunny sacks of spices with him, and he too sat in the back seat with me. Each started out shy, embarrassed, but burning with curiosity — each ended up wondering why we were doing this. At that point I was starting to wonder myself.

One happy passenger after another, we were finally well and truly on our way. Harur was in sight. Our team phone was low on battery, so we had no communications from the Mothership (the convoy) since the last time we spoke. We found that M., who was responsible for making sure all teams got rescued if anything went wrong, had been waiting in Harur for us for hours. His pickup truck was recognizable from afar, so we drove up to him. It was 4pm. All the teams started making their way up to Yercaud about 3 hours earlier. "So you better start now before it gets dark."

At Harur I don't think either of us had any idea we were only halfway there. It seemed such a tremendous accomplishment to have made it thus far. I started to feel relieved, like we could take things easy from here. We even celebrated with a 20 minute fresh fruit juice break. But we were to face a truly uphill battle.

We left Harur and made for Yercaud. We were so hot and dazed and frustrated by this point that even the relatively straight road towards Pappireddipatti, from which we would begin our ascent, was difficult to find. M. drove his pickup truck alongside, doing the convoy equivalent of kicking our asses, and we were finally in Yercaud!

Not so.

After 45 minutes up the hilly roads into Yercaud, a gear and brake problem we had been ignoring for the last four hours began to act up. The rumbling sound from the rickshaw was growing so much louder we had to pull over on the side of the hill. M. was not far behind, so we got him to take a look. Yet another 45 minutes spent not-moving, even though M. had really talented mechanics working with him, the sun began to fade. I have been to many places in the world and I'm supposed to be used to this — but it takes a huge effort for me to remember that when the sun sets, sometimes what follows is total darkness. And so it was. "Turn on the front lamps," I said to Andrew. "But… they are already on." They were just feeble, and really quite pointless. We could not see a single thing. M.'s team sped off and we soon lost them, driving in the dark ourselves. Our feeble lights did as much as to allow us to see when something was immediately in our faces, but not much else.

We were heading to the base hotel, but there was still a substantial climb to make. We were probably driving in the dark for about an hour before we finally saw a sign that said "Glenrock Estate" — our base camp for the next two days. Despite following the signs, and the instructions we received earlier, we could not find it. We would go straight, make a left bend, and then be in complete darkness again with no signs of a hotel anywhere near us. We kept going in what must have been circles in the dark. When we finally saw a bunch of lights, we knew it was not the hotel but the small village of Kakampatti. We pulled over for me to get some directions.

I ran into a store with a telephone, and dialled hopelessly for our friends. No luck — nobody had any cellular reception at the hotel. I asked a few villagers where Glenrock Estates was, and they said it was just ten minutes away, just up the slope we just came down from, where it was so dark we could not see the sign that said "turn right", so we missed that completely. When I got back to the rickshaw and to Andrew, he was on the ground peeking into the underside of our rickshaw. Disaster, yet again.

A bolt had fallen off the rickshaw some time in the last ten minutes. It could not start without this bolt — there was a risk the rickshaw would simply fall apart, if we did. But it couldn't even move at all. At this point I was beyond wanting to cry. Somehow I had some blind faith in how India always comes together for me.

A villager got on his motorcycle, and said he was going to buy the part for us from the garage 15 minutes away. When he returned, we found he bought the wrong bolt, and before we could even thank him for his help he got back on his motorcycle with someone who knew more about mechanics than he did, and they both went back to buy the proper part.

I sat on the ledge, wanting to help but really not being able to, just tired beyond belief. It's the sort of feeling when you are not sure when the work day will end — except in this case you don't know when the day will end, or whether you will get to where you need to be. I was fully prepared to spend the night in the village.

Suddenly, loud roars came riding down the hill towards us, and two men on quad-bikes came towards us.

"You must be Adrianna and Andrew."

I thought they must have been angels.

"We're the Bosen family, from Glenrock Estates. One of the village kids ran up here to tell us, quite breathlessly, that there were two foreigners whose rickshaw had broken down in their village. Since you were the only people not here yet, we assumed it must be you."

The beauty of my mother India is in how in spite of the chaos, things come through. If you don't panic, if you don't worry too much, if you don't allow yourself to be swept away by how different, and how insane, India seems to you, she will be good to you. Our rickshaw stayed in Kakampatti that night, but we didn't have to — we got into the quad-bikes with the Bosens, and they brought us uphill to their comfortable coffee plantation estate where we joined the teams around the bonfire, with Kingfisher and coffee magically appearing each time we wanted some.

Coffee. Beer. Food. A comfortable bed, even though it was one I shared with 20 other beds in a dorm, I was happy we made it. Now that the worst was out of the way on the second day of the race, surely there could be no worse moments hereafter?

The villagers of Kakampatti fixed our rickshaw for us, and even drove it to the hotel when they were done.

Yercaud may not be in the Himalayas, or any other majestic mountain ranges, but as a compact and quaint hill station in the Shevaroy Hills it was all I needed it to be, right there and then.

Aside: Visit the Bosens at their lovely Glenrock Estates in Yercaud! Great coffee and quaint place to stay.

February 21, 2011

Madras to Thiruvannaamalai, 185km

I've often said India never calls for me, she mostly shouts. With India, there is no moderation: you either love her, or you hate her to death — she never cares for you, or you can't get enough of each other. It's clear which camp I fall into.

I could have been in class, somewhere in Singapore, dying in a statistics lecture on an unbearably hot day. A message would come in from friends in Mumbai — usually about their plans that weekend — and I would not be able to work, talk, study, or function. Not until I booked a ticket to India. I could never explain it, I just had to do it.

It was like that again when I sat at the void deck of my apartment, decked out in my funeral whites, missing my grandfather terribly, not knowing how I would ever stop. Other people need Prozac; India's yelling, honking and shouting did it for me. It did it for me every time I needed her.

When the horn sounded at flag-off, we left Kodambakkam High Road behind. The gaggle of reporters, photographers, radio personalities, curious onlookers and well-wishers faded into the distance. Our destination: Thiruvannaamalai.

If you looked on a map, the holy southern Indian city is merely 185 kilometres from Madras. If you took a bus, it would take just under five hours. If you travelled by car, perhaps three and a little bit. Since we took an autorickshaw, our estimated travel time was something like eight hours. Or before nightfall; whichever came first.

It takes a while to actually leave Madras. The city is a sprawling mess of neighbourhoods, many of them neat and compact and middle class and manicured — by Indian standards anyway. We passed Thousand Lights, rode on to Cathedral Road, our music thumping in our DIY in-rickshaw entertainment system.

Near Menaka Cards factory on Arcot Road I made us slow down to stare at the ridiculous sign I have always loved on the side of its building: "Marriages are made in heaven. Marriage cards are made in Menaka". We strode on confidently — empowered with the sort of zeal only people who knowingly embark on insane adventures can have — past Mount Road, on to Saidapet. Guindy. St Thomas Mount. Chennai Airport. And then it was the open road from there, our first "highway" on an autorickshaw.

From then on we were well and truly on our own. We would lose sight of all the other rickshaws in the rally, most of the time, and only run into them when someone broke down, when we ran into another team in a random village, or when we caught up with the rest of them somewhere on the road. It would be up to us to decide which way to go and how to get there.

Relief.

Most mornings we were armed with little else other than the name of our final destination. At our daily morning briefings we were given tasks, and sometimes hints of how we should make our approach, but that did not preclude the fact that we would be waving our arms frantically outside our rickshaw most of the day, shouting at someone who was walking, or riding a bike or rickshaw: "Thambi! Chengalpattu, where? Left-ah? Right-ah?"

We perfected the art of speaking without words. Most times we received instructions with a bob of the head, and we replied and expressed our gratitude in the same way.

Thiruvannaamalai was not a difficult destination to get to. Excited and pumped with adrenalin, we raced our rickshaw through the Great Southern Trunk Road and then the National Highways like champs on three wheels. We stopped when we found the first breakdown of the day, Tim and Gary's, but otherwise stopped only to refuel, and to drink sugarcane juice. We got there fairly quickly, and without much incident. (Other than when we'd stopped for a train crossing in a small village, and a little girl came up to me to ask, "aunty aunty, what are you, white or Indian?" I said I was yellow, and drove off before she could ask me what a yellow person was.)

Chengalpattu. Tindivanam. Vallam. We stopped outside Gingee Fort to take photos of the fort and of the bulls with painted blue horns. Pennathur.

I have a love-hate relationship with India's religious, holy cities. I know how my skin colour, and the fact that I was born outside the structures and strictures of traditional Hinduism, means I will never encounter holy life in an Indian holy city the way it was meant to be; I will always be an outsider, always a firingi, in the religious places far more than in most other cities. It also means I see much more of the harassment and the stupidity that their most aggravatingly frustrating touts and pimps and drug dealers subject to foreigners, who believe we all come to India's holy places to seek darshan with the gods of drugs and sex, without exception, and must thus be given what we want: sex and drugs. In Benares I felt no holiness, only sexual harassment; I did not have high hopes then for Thiruvannaamalai.

Karthik at a rest stop.

By the time we found Chengam Road, with some difficulty, it was already dusk. The town's sacred vibe was apparent: in addition to the numerous temples, priests and sadhus, there were a great many white people in what I call "enlightenment attire", wandering around town. When we pulled in into the grounds of our first base hotel, a fancy resort along Chengam Road, we were tired, but victorious.

I could not have asked for a better way to end the Rickshaw Challenge, having had such a great first day; but something about Thiruvannaamalai did not sit well with me. The hotel's staff started off friendly and grovelling, but when they found out my team did not intend to plan to stay the night and spend a ridiculous sum on their "affordable luxury" they quickly turned sour. The cheap hotels we wanted to stay in were sneered at by them — we CANNOT stay in those hotels, they said, because "these hotels allow smoking", and "they serve alcohol and meat." I have utmost respect for teetotalers, vegetarians and non-smokers, but it's this sort of holier-than-thou attitude practised by a small number of you that makes me run in the opposite direction and do those very things you dislike.

So off we went, back onto Chengam Road, back towards the town centre, in search of the Promise Land: a cheap hotel with alcohol and meat.

We were turned away by many budget and mid-range hotels, because I was "gasp a WOMAN!" I was a woman who intended to share a room with a white man and an Indian man, but the idea was inconceivable to many. I was told by several hotels that they were looking out for me by not letting me stay there, to protect my honour or something flaky like that. Others said they were protecting me from the many bachelors who stay in their hotels, as though these bachelors would not know how to deal with the presence of a Chinese woman in a rickshaw wallah uniform. Dejected, exhausted, and still ranting about self-righteous vegetarians, we finally settled for a bright pink hotel with a decent fan room for a handful of rupees.

A shower never felt so good.

I slept on the floor, deciding it was preferable to the hard double bed shared by the boys, and dreamed a long dream about driving down the Great Southern Trunk Road.

Tomorrow, we would conquer Yercaud.

February 13, 2011

Madras, India

There are slower ways of seeing India. On a buffalo. On a "two wheeler", a motorcycle, stacked to great heights with assorted luggage until you can't see what's in front of you. Or on foot, "by walk", like a sadhu with no clothes on.

We travelled by autorickshaw.

An autorickshaw isn't too bad an idea on paper: it is, after all, capable of hitting up to 50km per hour. Which would be comforting if our speedometer actually worked. Instead, ours wavered meekly several times per day, mostly settling for the number 65. How machines lie. I wouldn't even call our autorickshaw a machine — a primitive piece of equipment, yes, but machine, implying any form of mechanical achievement or efficiency, no.

We set off from Madras one hot morning, dressed to the nines. It was a good idea before flag-off, this brilliant idea we had of dressing just like a rickshaw wallah. The previous nights we had been in Pondy Bazaar every night, looking for various items to complete our get up. We'd planned to dress as Super Mario characters at first. The mustache and beret were no problem, the theatre costume company we'd checked out earlier had plenty of those things. They were initially designed for Roman centurion characters and other popular roles, such as various Hindu gods, but we could appropriate those items to create our Mario outfit. But the suspenders were impossible. Even the salesmen at Saravana Stores laughed at us when Karthik described what we wanted. "You mean you want dungarees, saar? They're so old-fashioned. You cannot find them in Madras. They're too old-fashioned, saar, we have no dungarees." If a Madras salesman tells you they are out of fashion, they are out of fashion. So we thought we'd dress like a rickshaw wallah instead.

Saravana Stores is a bit like Singapore's Mustafa Centre. Mustafa scores better on the "has all the crap you ever need to buy" front, but Saravana wins on the "has an entire section of the store dedicated to rickshaw men's uniforms" front. We skipped over like crazy firingis, trying out different types of singlets (who knew there were so many?); a variety of khaki shirts, and patterned lungis. A few hundred rupees later, we were in business.

The author dressed as a rickshaw wallah with a tilak.

We took off from our base in Kodambakkam High Road, much to the delight of the local press. I was interviewed several times, very likely because I was a girl with a tilak on her head, dressed like an autorickshaw man (thereby bending gender norms a little bit). I smiled nicely and fiddled with my lungi, and put on my best I am a foreigner accent. All was forgiven. Foreigners can do whatever the hell they want because we're all supposed to be crazy. Crazy enough to be driving a three-wheeler for 21 days continuously anyway.

Among the many questions posed to us by the Indian media, the one I could not answer was, "What do you hope to achieve by doing this? What is your intention?" Insanity has no intentions. It simply happens. Likewise, when I first read about the Rickshaw Challenge five years ago in Wired, I knew I had to go. The insanity took over and consumed me until I finally bit the bullet and went for it.

Where we would live, where we would spend our nights, how we would repair our auto when it broke down (and we knew it would break down at least once a day), I had no idea. Everyone else had booked the hotel package that came with the race, but we were too cheap adventurous for that. If we were going to see South India the way none of us had ever seen her before, we would do it the proper way. We would drive an auto everywhere and we would stay anywhere, as long as it was close to a TASMAC and a good breakfast.

With that policy of insanity and inebriation firmly in mind, we set off for the open road, cruising on the East Coast Road. It was one of the happiest moments of my life.

December 1, 2008

I don’t have to tell you what happened in Mumbai. You already know it. I wasn’t there that day, and although I may at some point in the future, I have never lived here. Not in the real sense of ‘living’ somewhere, with bank accounts and rented residences, or jobs. But Mumbai is my city, my friends are Mumbaikars, and I feel every bit one myself: I still call it Bombay, because Bombay is romantic and real and Mumbai isn’t; I love the city, have my favourite haunts in Bombay, both north and south, and know the city well.

Perhaps too well.

On any regular Bombay evening, my friends and I would be sitting at Cafe Leopold in Colaba Causeway. I’m there every night, not that I particularly like it. When the papers and news reports tell you the gunmen threw a grenade into a ‘popular tourist cafe’ in Colaba, you need to know first that Leopold isn’t just any popular cafe, Colaba isn’t any regular street… and Bombay isn’t any regular city. Leopold had a strange, inexplicable draw. Mr Shantaram was there, back when he was actually living in the slum a few streets behind it, and so were the real life cast that inspired his fictional motley crew of Bombay misfits, mafia and other things. Even now that Johnny Depp is going to play him in the movie, now that he’s a minor celebrity, he is still there. You never quite leave Leopold.

My friends and I at Leopold would just be like any regular bunch of friends who might be sitting there that night. Young and foreign — photographers, wannabe Bollywood stars, scruffy Bollywood recruiters, writers. Drawn by the magic of Leopold: the bad music, the bad pasta, the Kingfisher and Cobra beer that was never terribly cold, but the coldest the city could give. And our friends: each other, and the chattering yuppie Indian middle classes. When we were done someone might say, let’s go for a kebab. We’d pop around the corner to the famous Bade Miya, just down the road from the Taj, sit in a derelict building outrageously (and illegally) outfitted with fluorescent lights, while more young scruffy expats and Indophiles like me sat with each other and with our yuppie middle class Indian friends — smoking, eating with our hands, and perhaps someone would say let’s go to the sea.

Bombay is a city by the sea, but not in the usual sense of it. It’s beautiful, but only if you look hard. The Arabian sea engulfs it on one side, and on a hot Bombay night there is nothing more entertaining than sitting by the Arabian Sea, eating bhelpuri and drinking_chai_ with your love — and Bombay is a city for lovers — on Juhu Beach or by the rails along Marine Drive. You’d look out to the domain of old Bombay money, Napean Sea Road and Malabar Hill, shimmering away in the distance. The majestic Taj hotel behind you. The Gateway of India, and all its pigeons and pigeon shit and tourists, to your left. Bom Bahai, Bombay, Bom Bahai the good harbour, as the Portuguese called it.

And CST was where it all started and ended. Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, so renamed to please the frothing at the mouth Shiv Sena, Marathi supremists and their Shivaji cultists. Victoria Terminus, or VT, was what the rest of us called it. You entered Bombay at VT, stepped over sleeping bodies, crouched all over the station and platform floor. They never did that in ones, rarely twos — the Indians do everything in groups, and especially in Bombay groups of ten, twenty, will all be sleeping, chatting, sitting, drinking tea on the floor, squatting by their ancient-looking luggages, waiting for trains to take them homes. Some of them would have just got in to Bombay, destined to a lifetime of pavement-sleeping in this crowded city; others would be veterans, waiting to go home for the week after months or years in the big city. You can tell who’s been here for a while by the way they talk about the city: there’s a certain degree of Bombay smugness. Or perhaps smug is not the word — it’s the air of knowing. When you know Bombay, whether you’ve lived there all your life, whether you’re Parsi, Gujarati, Malayali, Singaporean, American, British, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, whether you go back to sleeping on your pavement, to a Malabar Hill Road address or your expensive room at the Oberoi. It doesn’t matter. When Bombay is your city, it shows. Whether you stepped out into Bombay in the morning at CST, or in the dead of night, they were there. And to get out you had to step over them, shove your way through the porters, and the thronging multitude carrying what seems to be hundreds of kilograms of things they were carting home: sweets, hay stacks, goods. When you left Bombay, you did so at CST too. If you left for a day trip you might go to a place like Matheran, where I like going whenever I’m in Bombay, and you’d take the train from CST to Neral Junction to get there. If you lived in Bombay, especially in the north, you would take a train home from CST, too. You’d get on one of those dangerously overcrowded suburban locals, the ones I so love.

But it all fell apart. The city of dreams is burning. Those sleeping bodies on the station floor are probably all dead, and so are the waiters at Leopold — two of them. So are the sorts of people I might have met and chatted up at Leopold. Heck, my career started in Leopold when a roving photojournalist chatted me up there and we found we had an incredible chemistry and worked well as a team, sealed off with Kingfisher, Gold Flakes, and Indian whisky at Gokul just around the corner. I never went to the Taj or to the Oberoi but as India’s finest hotels, they are not mere hotels — they are symbols, testament to the power of this city and its dreams. As a young man Ratan Tata’s great grandfather, Jamshetji Nusserwanji Tata, walked into the colonial Watson’s hotel and was turned away — because he was Indian. He vowed to build a grander hotel than that, and he did: the Taj hotels are the pride of India, and the Taj Mahal in Bombay was the crown in the jewel: the Beatles stayed there, and so did endless other kings and queens, especially the ones that matter most to the Indians, the cricketing gods. For the pavement-sleepers, scruffy backpackers, middle class Indian tourists, and locals alike, The Taj was — and still is — the landmark in the city by the sea.

If something like this could happen to any city, it would be to Bombay, and it would be to these sites of great emotional resonance. The city has never been an easy one to live in. It is full of crumbling buildings and bureaucracy, it is the symbol of Indian inequality of class, wealth and status, it is the city full of people who have nothing right by the people who have everything. It is hard to imagine why anyone would live here. But Bombay, like Leopold and its terrible pasta, like the Taj and the Oberoi and its occasionally contrived grandeur, has an inexplicable aura that draws her people — and their hearts — to her. And she demands you love her despite the terror attacks, despite the gangland wars, despite the everyday inconveniences of living in a place like this with no living space, no drinking water and no dignity.