Wet markets have a bad reputation, because of the 'rona, but their name really just comes from being the opposite of a 'dry market' (like a market that sells pots and pans and such). They are very common in many parts of Asia and don't have wildlife. For many of us, a wet market is our first port of call to make the delicious foods from our part of the world.

These photos are from a wet market in Taiping, Perak, my wife's hometown. We visited with my mother-in-law and her sister, who were preparing a large family feast for the first reunion in the Taiping home in a very, very long time.

Eggs

Salted fish

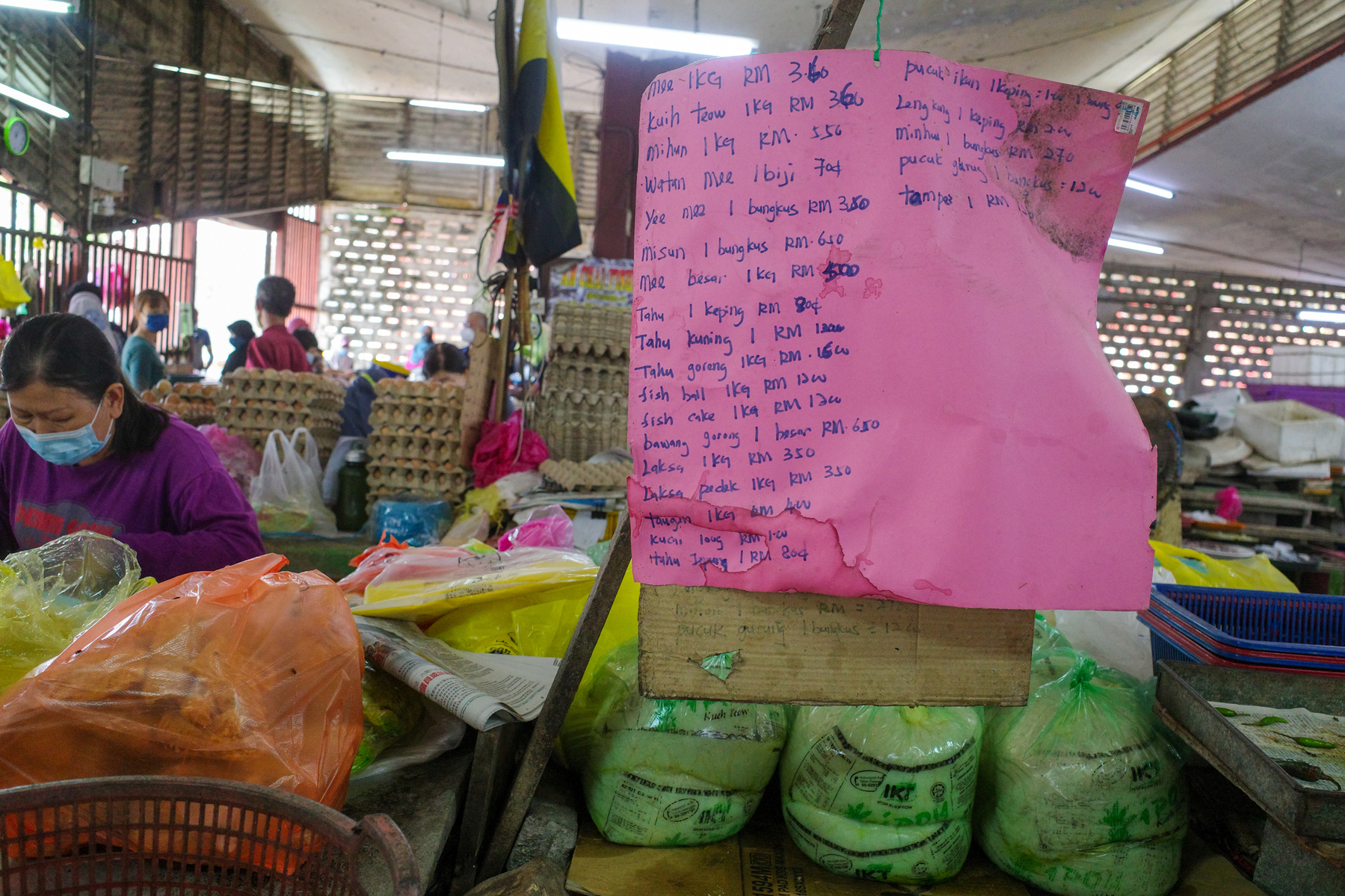

Essential items

Aromatics

Potatoes

Sambal

I can still taste that sambal. What passes for sambal in the United States (Huy Fong sambal oelek!!) makes me so, so sad.

Lately, I've been thinking about how growing up in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore (and spending lots of time in Thailand, Indonesia, India) really spoiled me where food is concerned.

The food ways I am used to: buying fresh food. On a daily basis. At wet markets. Learning to cook traditional foods from skilled older people from different cultures.

All of those things are vastly different from a convenience-first food culture where I now live in the United States. Even though California, and San Francisco in particular, has a reputation for being farm to table, and for having good quality food, I do find myself feeling, quite often, like I never knew how good I had it until I left Southeast Asia. California is good, for food: my part of the world is better. That's how I feel, anyway. Being able to wake up in any of those countries and grabbing one of many hot breakfasts. Being able to eat hot, savory, spicy food all day, everyday, including at 3 or 5 in the morning. Being spoiled silly, really, by aunties of all types. Being surrounded by people who want to feed you all day, every single day.

Taiping, Perak in Malaysia is one of my favorite little towns. It has beautiful weather and scenery, an interesting history, and some of the best food I've had anywhere. I dreamed of the simple bowls of noodle soups I've had there (Restoran Kakak!!!), for years, until I went back again in 2022 to visit my wife's family. You've not had noodles until you've had the kway teow tng at Restoran Kakak. It takes skill, and really 'giving a damn' to make food like that. I think Taiping (and Perak as a whole) has a higher density of people who 'give a damn (about making food in a very specific way)'. And that's just normal, there.